- Opinion

- 14 Aug 23

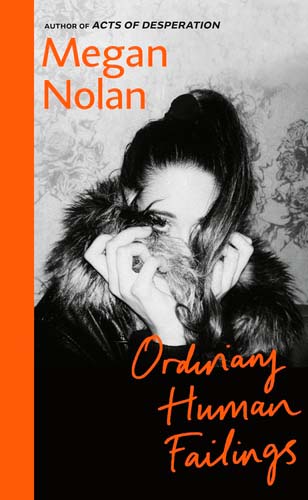

Megan Nolan: "The nightmare is that you actually have to have the baby if you have an unwanted pregnancy. That was really intense, writing about that"

Back with her hugely anticipated second novel Ordinary Human Failings, Megan Nolan discusses research methods, her love of Waterford, addiction stigma, and the pain of unwanted pregnancy.

Megan Nolan is just off the train when she steps into the Hot Press office, ahead of a day of book signings around the city centre. The 33-year-old Waterford native is in good spirits as she embarks on the promotional tour for Ordinary Human Failings. Having published her debut novel Acts Of Desperation in March 2021, which focused on coercive control in raw detail, Nolan’s latest opus is a curveball. The London-based writer’s versatility isn’t surprising, however, given her work as a features journalist for The Guardian, The New York Times and more.

Ordinary Human Failings is set in ’90s London, where ruthless tabloid hack Tom Hargreaves is seeking to further his career as a reporter. He accidentally stumbles upon a “splash” – a child found dead on a London estate – whose parents are well known in the community. The suspicion is immediately placed on a family of Waterford immigrants, and in particular 10-year-old Lucy. With the police questioning her, Tom’s newspaper sets the Green family up in a hotel to wrench their secrets from them under the guise of enabling them to hide.

“I started developing this idea in about 2019, after we sold the first book,” Megan recalls, sitting in Hot Press HQ. “I read an anecdote in a nonfiction book that struck me. I wasn’t keen on writing another first-person, intense, interior novel as my second. Acts Of Desperation was more heightened and theatrical. Ordinary Human Failings is much more out of my comfort zone, but the actual family members are the kind of people I grew up with in Waterford.

“The Greens aren’t based on anyone in particular, but it didn’t feel like a stretch to go down that road. With the crime itself, I read a book called Children Who Kill [Profiles of Pre-Teen and Teenage Killers by Carol Anne Davis]. It’s not about killing, it’s about children who are capable of all sorts of extreme behaviours. It’s a psychological textbook about the commonalities between different kids who carry out these violent acts.

“There are alternating motivations for all of the children, but there are some pretty striking things in common. Some of them are obvious, like physically abusive parents, but it can sometimes be subtle, benign neglect – like disinterest and disengagement. For some children, that affects them strongly. It can create very disjointed relationships with other people.

“When you’re a kid, you’re not born knowing what’s imagined versus real. They have a very fluctuating sense of the permanence of death. It’s really hard to concretely say that a child of Lucy’s age in the book knew what death was. With an adult, you can assume that we all have a shared understanding of death’s permanence.”

The history of English tabloids is fraught with scandals, often incredibly harrowing ones.

“I read a few memoirs by retired tabloid hacks, which were written pre-Leveson inquiry, so the culture wasn’t as damning,” Nolan adds. “They were shameless about saying all of the wild stuff they were doing. Bragging about fucked-up things. One of them relayed a story about a colleague who had gone into some grieving mother’s home and seduced her while she was out of her mind with trauma over her son. All of this shocking, immoral material. Their guiding light was just to write the newspaper, and that superseded everything else.”

When it comes to children implicated in deeply disturbing crimes, the public craves a concrete reason for their motivation; a troubled background or psychopathic traits.

“Because the basis of the book is an objection to that sort of simplicity, readers seem to understand why I was trying to go against that X, Y and Z notion,” Megan posits. “The novel is quite literally about things that happened in the past that you can trace to the present, but I really don’t like the mathematics around trauma: ‘Lucy was abused, that’s why X happened’. I didn’t want to be simplistic about it, but I also wanted to acknowledge that generational trauma exists. It’s much more nuanced than most accounts would portray.”

The novel also tells the tale of Lucy’s mother Carmel: her secret teenage love affair and a dissociated refusal to accept the resulting pregnancy. Her depressive struggle with unwanted motherhood and inability to face reality leads to a lonely childhood for Lucy. Carmel’s dutiful late mother, Rose, and her marriage to the withdrawn, hard-drinking John, who was heartbroken by a previous wife, are also told beautifully. Most excruciating is the story of their lonely, alcoholic son Richie, who drinks to fill a gaping wound of loneliness.

“I felt the most connected to Richie,” Megan nods. “It’s weird, because Carmel’s experiences are the ones which I can relate to more in terms of pregnancy and being a young girl in love. I found that I cared for Richie in this really intense way. Almost everyone in the world knows someone who is an alcoholic, or has a tendency towards self-destruction. I was thinking about how it felt to see someone who’s not stupid, but is behaving in these ways which look completely illogical from the outside.

“You can’t help them, and they can’t help themselves. That’s incredibly sad. A lot of people have to watch someone in their family do this. The ending of the book suggests in a broad way that this catastrophic event has exploded the family so much that their historical silences aren’t possible anymore.”

Addiction is only one painful road the novel travels down, but it makes a gut-punch impact.

“A lot of the book’s topics are issues I fear or have come close to. I wrote them out to their worst extent,” Megan concedes, frankly. “I wanted each character to have a moment that happened in their past that was private from each other. With Carmel, I never had a baby but I was pregnant. I had a similar experience to what was described. The nightmare is that you actually have to have the baby if you have an unwanted pregnancy.

“That was really intense, writing about that. Similarly, for Richie’s segment, this loneliness that makes him drink to be near other people – I’ve definitely had that urge, even though it pushes people away. Most of us learn to moderate behaviour, but Richie doesn’t. That was tough to write.”

Carmel’s ability to self-harm her pregnancy into something intangible is painful to read.

“It’s not far removed from the past. Repeal was only five years ago,” Megan notes. “I’d be curious to know how different my feelings would be about pregnancy in general if I grew up now in Ireland. Even at the age of 33, I’m scared by the prospect of accidental pregnancy. When you’re growing up with certain societal norms, you don’t really think about them. We were taught that the worst thing that could happen to you was getting pregnant. That was the biggest fear, even way before my friends and I were having sex. Somehow we were still afraid. That’s constantly on your mind, but you’re likely getting teased for being ‘frigid’.”

Repeal the Eight Referendum Results announcement at Dublin Castle/ Photo: Allen Kiely

Have attitudes towards addiction evolved, in Nolan’s view?

“With alcohol specifically, it’s just a nightmare subject that nobody wants to go near,” she replies, shaking her head. “I find that, especially when I talk about my own drinking habits, unless you’re sober, no one wants to talk about the issue in general. If you’re still drinking, they don’t want to be implicated in the idea that alcohol is dangerous or can be troubling.

“People in Ireland are so gross about drug addicts in a way that I don’t see in other countries. They’re so vitriolic here and the language around it is so extreme. Genuinely, I’m very taken aback by the way in which people speak about it. It’s not because people are more polite about it in England or America, they just don’t actually have that really fucking horrible attitude. I don’t understand why it’s so bilious in Dublin. I’ve never had a drug addiction, but I can’t understand how people can’t conceptualise how hellish it is. Why are you furious at someone who you can see is in fucking agony anyway?”

As an emigrant, did she enjoy including her hometown in the novel?

“It was fun, because I was writing it in London, but had to be in that place mentally,” says Megan. “It’s small, and my parents moved all over it as a kid, so anywhere that’s mentioned in the book, I’ve probably lived there at some point. It was really pleasurable. It’s nice to have an excuse to ask my dad what the cinema was called there in 1980, and figuring out what a specific pub would have been called back then. People from Waterford really love Waterford.”

• Ordinary Human Failings is out now via Jonathan Cape.