- Opinion

- 03 Aug 22

Chris Blackwell is the kind of record man they don’t really make anymore, with a career that went from selling records out of the back of his Mini to conquering the world with Bob Marley and U2. “I was spoiled,” he tells Pat Carty.

The greatest record company of them all? I might nominate Chess or Stax, amongst others, but you can’t even begin that conversation without mentioning Island Records, the label who championed everyone from Burning Spear to Tom Waits, and the creation of one man, Chris Blackwell.

Blackwell’s new auto-ish (journalist and friend Paul Morley helped out) biography, The Islander: My Life In Music And Beyond, tells the company’s tale and it is a capital yarn, beginning in Blackwell’s native Jamaica where the likes of Errol Flynn, Ian Fleming and Noel Coward were friends of the well-off family.

“Flynn was a very good looking guy,” Blackwell tells me, with considerable understatement, over a creaky Zoom connection from Jamaica, where the sunshine coming through the window behind him looks like a special effect. “I met him when he arrived in Jamaica, a very bad time in his life when he had a fight with Warner Brothers Studios, but he was terrific; full of laughter, a strong character.”

The "criminally good-looking" Errol Flynn

The "criminally good-looking" Errol FlynnAdvertisement

Blackwell describes Flynn in his book as "a criminally good-looking man and a flamboyant hedonist with a roving eye for both women and men." He also attempted - unsuccessfully - to put the moves on Blackwell's mother, several times. Here's more of it.

"Errol knew how to live large. He was the first person I ever saw water-ski, with a nonchalance that made it seem like he was just going for a stroll. When I was fifteen, I watched as he glided onto the Port Antonio beach dressed for cocktails, with a cigarette holder in his fist and a dachshund under his arm. It was the coolest thing I have ever seen."

Given the many, many cool things Blackwell would go on to see, this is no small claim.

Blackwell entered the music business through stocking Wurlitzers on the island, then buying precious records for the sound systems on his trips abroad, but it was with water sports again that Island got started.

“Lance Haywood was the first album I did,” he remembers. “I was teaching water-skiing at a hotel in Jamaica called The Half-Moon. Lance was from Bermuda and he’d been brought in to play during the season. I guess I’d had a couple of drinks and I said ‘I’d love to record you guys’ – though I didn’t know what I was doing – and they held me to it. There was just something about producing that record and living that life that I really wanted to do.”

The serial number was Island CB21, indicating Blackwood’s initials and his age, and the Island name came from the Harry Belafonte movie, Island In The Sun. Blackwell was hooked. Fast forward slightly to 1962 and he had relocated to London, having hit on the scheme of selling his competitors records - out of the back of his Mini - to the recently immigrated West Indian population.

Advertisement

Catalogue Number CB21

Catalogue Number CB21“I loved every minute of it,” he smiles. “I was driving all around the periphery of London, the areas where the Jamaicans lived. Going into a store playing them a record and saying you should take twenty-five of this. I was always very careful to maintain good relationships with them so that they believed in what we were doing.”

Hearing a voice he couldn’t ignore, he recorded ‘My Boy Lollipop’ – a song picked up on a New York record buying trip – with fellow Jamaican Millie Small in 1964. It was an unprecedented smash – “I knew it was going to be a hit, I just knew,” Blackwell maintains – selling 7 million copies and launching Island as a going concern.

Next Blackwell walked up some stairs in a Birmingham club and heard what “sounded like Ray Charles singing in a high-pitched voice”. This was Steve Winwood, fronting The Spencer Davis Group. Blackwell put them together with a song by Jackie Edwards called ‘Keep On Running’ and they were soon knocking The Beatles off the top spot.

Both these hits had been licensed out to the larger Fontana label – “a small independent company can have a big hit, but you cannot get paid” – but Island came into its own with the release of the debut single by Traffic – what Steve Winwood did next – in May 1967. ‘Paper Sun’ was the first record to sport the pink Island label that is now so precious to collectors. Trojan Records was founded by Blackwell and Lee Gopthal the following year to concentrate on Jamaican music, and Island forged ahead as “things were happening with Traffic, Free, Spooky Tooth, and all that kind of thing”

Advertisement

I’m flying though history here to allow Blackwell, a charming and polite gentleman of the old stripe, as much space as possible to relate his memories of Island’s heavy hitters. Despite skipping several, the names that pop up – which I prompt by holding up some of the many albums bearing the Island imprint in my house – read like a who’s who of popular music.

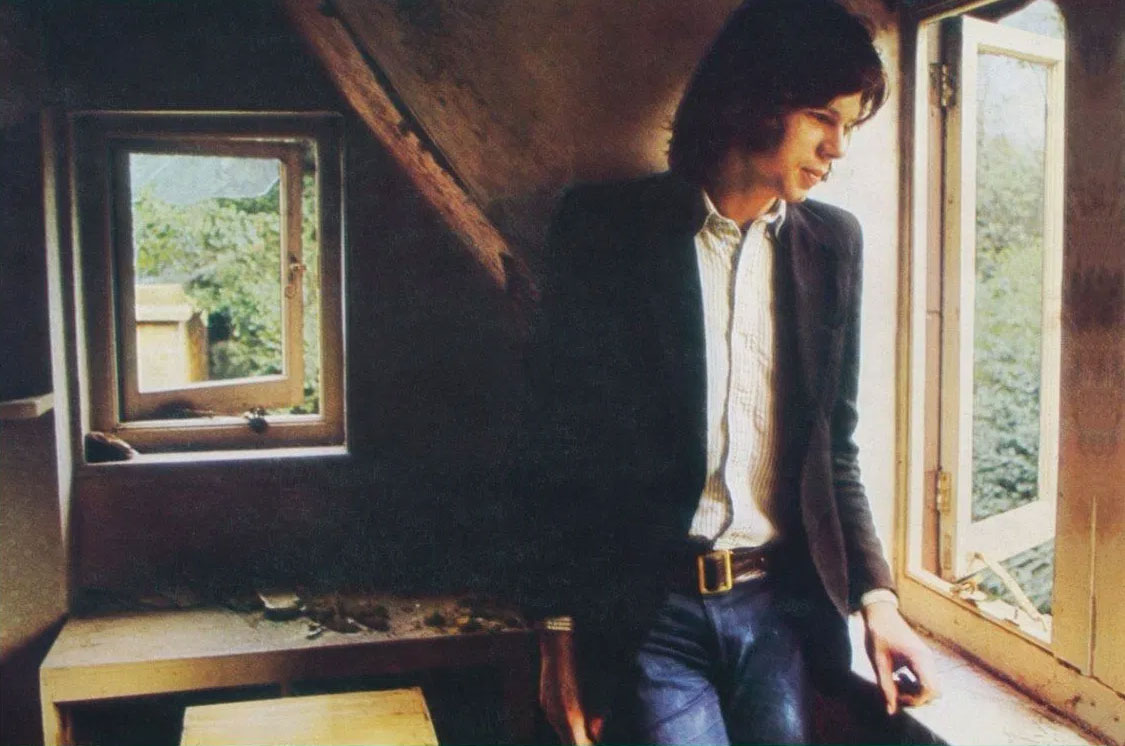

Bryter Layter

A very young Nick Drake came to see Blackwell in 1967, possibly at the prompting of his friend, John Martyn. Blackwell told him to come back in six months.

“I was right in the middle of Spencer Davis Group turning into Traffic and Spooky Tooth, “he explains. “It was more sort of hard rock. Nick’s music was fantastic, no question about it, but I didn’t feel I could devote the time to guide him. He came back but unfortunately everything was pretty much the same. If I felt I could have brought something to the table, I would have done that in a second.”

Joe Boyd, an American folk music savant who had tried and failed to get his former employees, Elektra Records, to sign Syd Barrett’s Pink Floyd, had a management and production company called Witchseason which signed a deal with Island, leading to the release of such masterpieces as Fairport Convention’s Liege & Lief in 1967 and, later on, the likes of Richard and Linda Thompson’s I Want To See The Bright Lights. Drake was part of Witchseason so his debut Five Leaves Left came out on Island in 1967. In the book, Blackwell lovingly describes how Drake recorded ‘River Man’ live with Harry Robinson’s strings, an arrangement Blackwell considers to be even better than ‘Eleanor Rigby’. Despite this, the record didn’t sell. At all.

“I liked Nick’s music a lot but how are you going to market it, where do you promote it? I was doing a lot of things, too many things. I don’t know if it had the attention it should have had.”

Advertisement

The last time Blackwell met Drake, who died in 1974, was when the singer delivered his final album Pink Moon, to the Island offices.

“I remember it clear as a bell,” says Blackwell now. “They said Drake was downstairs, he was just sitting on a chair, looking down, with a small little tape reel. I sat next to him. ‘Hi Nick, how are you?’ There wasn’t much coming from him. I told him I was looking forward to hearing the new album, then he left and that was the last I saw of him.”

Boyd stipulated in the contract when he sold Witchseason to Island that Drake’s recordings must never be deleted from the catalogue. As Blackwell relates on the page, sales remained non-existent until Volkswagen used ‘Pink Moon’ in an advertisement in 1999, boosting the numbers literally overnight.

“That’s how this business works. Something can come up suddenly. You think, how is he connected to a Volkswagen but they felt it was a piece of music that would work. That was what he deserved, from day one. I felt he had magic.”

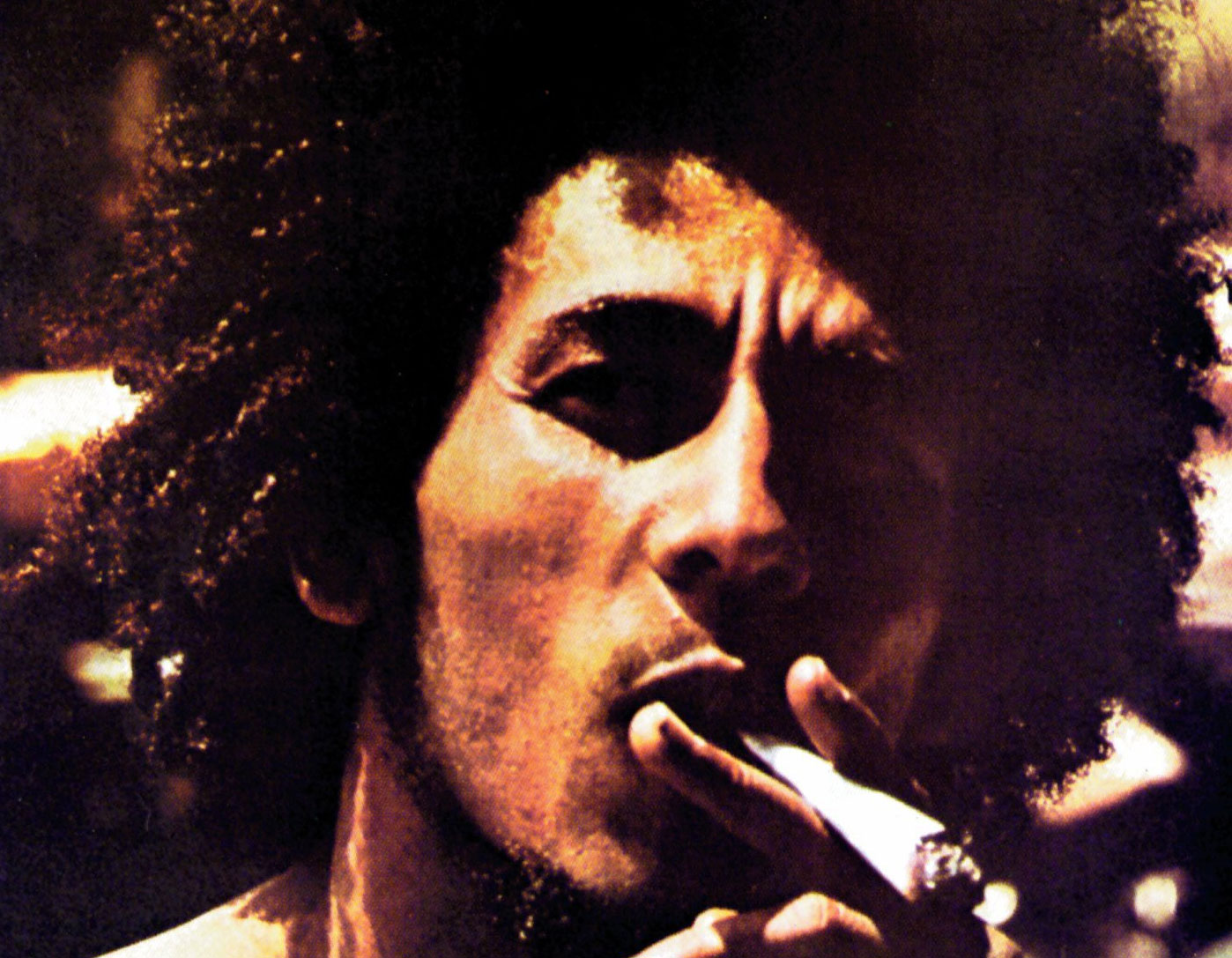

Natural Mystic

The 1972 Jamaican crime movie The Harder They Come, co-produced by an uncredited Blackwell, helped Reggae music begin to cross over.

Advertisement

“It was the major thing, because it gave you a feel of what the music and the life was all about, and it was very well done. I was in Brixton when they showed it and the whole cinema was full of smoke!”

The movie starred Jimmy Cliff, who had been working with Blackwell, but parted company with Island before the breakthrough came, taking an offer from EMI. The same week, three other young Jamaicans – Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, and Bunny Wailer - walked through the door. Here’s how Blackwell describes the scene.

“They were immediately something else, these three strong characters… As I took the measure of them, I thought, Fuck, this is the real thing.”

“It wasn’t the same week, it was the next day,” Blackwell corrects me before taking up the story. “They were stranded in London with no money, no way to get back to Jamaica. I said yes because I was pissed off Jimmy Cliff had left. I guaranteed them some money for the trip back to Jamaica and to do the record.”

There must have been – and there was – people who told Blackwell he was never going to see that money again.

“That’s the advantage of owning a company and not working for one,” he smiles. “Because I’d have been fired, but I believed in them.”

A couple of months later, Blackwell turned up – as instructed - at the small shop in Kingston out of which the Wailers ran their Tuff Gong Label.

Advertisement

“I was hoping they’d recorded something,” he says, reasonably enough. “I spoke to Rita [Marley] who was running the shop who said ‘I think you’ll like it’. They came and picked me up at my hotel – Peter, Bunny, and Bob – and we went to the studio, listened to the recordings, and I knew they were great.”

These was the original Jamaican version of the first Wailers Island album, Catch A Fire. As brilliant as these recordings were, Blackwell was canny enough to take them back to London to add something more.

“I did want them to open up. Bob already knew ‘Rabbit’ Bunderick [keyboard player with both The Who and Free, who added synth and clavinet] but Wayne Perkins [the American guitarist you can hear on ‘Slave Driver’, ‘Stir It Up, and ‘Baby We Got A Date’] couldn’t get a grip of the reggae rhythm at all. He found it eventually and gave the album it’s incredible opening.”

Burnin’ and Natty Dread followed the critically acclaimed Catch A Fire, with Marley emerging as The Wailers’ main man. A breakthrough of sorts came with the Live! album, recorded over two nights at London’s Lyceum in 1975. The story goes that the sound of the audience was turned up at Blackwell’s insistence.

“I said it to the sound people before the show started. The reason we did that show is because about two or three weeks before that Bob played The Roxy in Los Angeles and when ‘No Woman, No Cry’ came up, there was a whole corner of the audience singing the chorus. I knew a recording of that would take off. It was luck in a way but we caught that atmosphere.”

Elsewhere, Blackwell has claimed that he only really ever produced one Bob Marley song, the final track on the last album released during Marley’s life time, 1980’s Uprising.

Advertisement

“I liked ‘Redemption Song’ but I didn’t think it should be like that [the full band arrangement]. Bob wondered how it was going to work with the rest of the record so we just put it as the last track. He played it three times, we edited the middle one, and that was it. The lyrics are so powerful and it’s so much what Bob Marley was all about. It’s not just about dancing, there’s a real sense of importance in his music. That’s why I wanted it to be heard like that.”

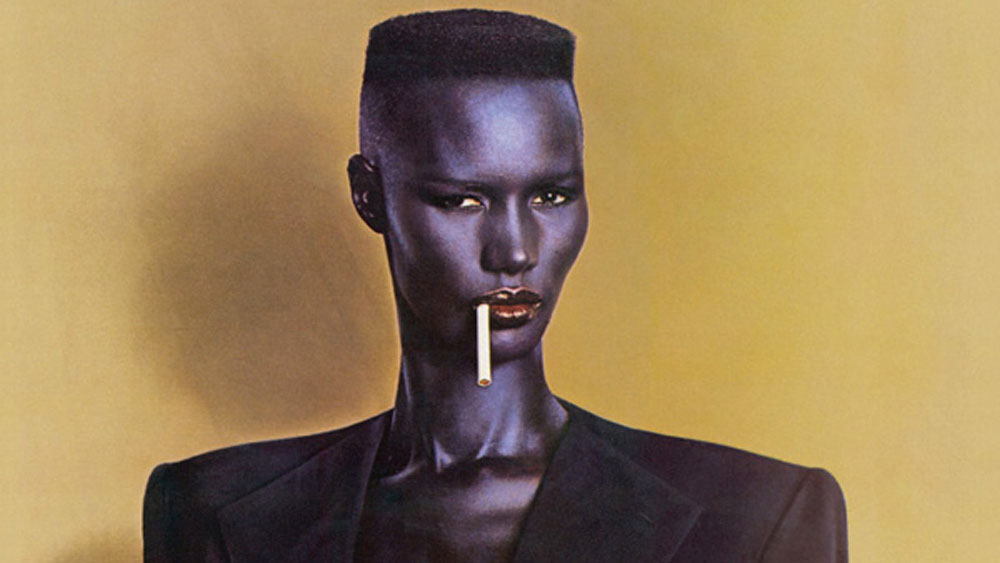

Ladies And Gentlemen: Miss Grace Jones

Blackwell first encountered his next Jamaican superstar in a magazine photo.

“It was Nik Cohn [the British music writer who inspired both ‘Pinball Wizard’ and Saturday Night Fever] who told me there was a Jamaican girl in New York who was a great singer, and a couple of days later I opened a magazine and there was Grace Jones, standing on one leg.”

“I tracked her down and she was trying to make it, working on a record, and she had talked people who were in the clothing business into financing it. She said I should hear what she was doing, so they came up and they put on this record, it’s called Portfolio. Do you know it?”

I do, it’s the one with ‘La Vie En Rose’.

Advertisement

‘That’s right. I was there to listen to this girl, who was really stunning, singing, but the first four minutes was a drum machine. I thought it was a disaster until her voice came in, then it took off.”

It was Blackwell’s idea to decamp to his new Compass Point studio complex in the Bahamas and build a band around Jones, a group who came to be known as the Compass Point Allstars.

“I wanted Jamaican music, I wanted Sly & Robbie, and the percussion [Uziah ‘Sticky’ Thompson]. I wanted rock guitar, which was Barry Reynolds, who’d played on Marianne Faithful’s Broken English, and [on keyboards] Wally Badarou, who had produced a record in Europe which was a huge hit, I can’t remember who did it though. [He may be thinking of M’s ‘Pop Muzik, which Badarou played on]. I invited them all down to meet at Compass Point and for the first couple of days it didn’t look like it was going to do too well. Sly & Robbie can be a bit rough and ready and Wally was this well-dressed gentleman. They didn’t really hit it off so I put up the photograph of Grace on the wall and told everyone that the records should sound like this photo. That gave some focus and two or three days later it was like a love affair between all these musicians from different parts of the world.”

“Because her first producer was a DJ and not a record producer, Grace had never been in a studio with a band before. She was a bit shy at first but in no time at all she was strong. It just pulled together, it was a risky thing in a way but it worked.”

Warm Leatherette and Nightclubbing were recorded together in about a week, with unexpected song choices like Tom Petty’s ‘Breakdown’, prompted by Talking Heads Chris Frantz and Tina Weymouth, according to Blackwell, who would record the first Tom Tom Club album in Compass Point the same year. Petty even wrote Jones an extra verse. As Blackwell puts it, “We had found her sound, male and female, black and white, skin and metal, beauty and beast, European and Caribbean, American and alien. We made a genre of which there was only one exponent – Grace Jones.” On top of that, “she looks exactly the same now as when I met her in 1976,” says Chris, which is just unfair, really.

Stories For Boys

Blackwell first had his attention drawn to a young Irish band of hopefuls by Island’s head of Press.

Advertisement

“It was Rob Partridge and also Nick Stewart [A&R] who got very close with U2 and got them interested in Island.”

He first saw the band at the Half Moon in South London on June 7, 1980 and while the music didn’t grab him, something did.

“It was their passion, for a start. Their energy, their drive. I’ve said this a lot to people, but it is really important; they had a really solid manager. A manager is often a good pal, but in the case of U2, there was a proper, professional business person, who believed in the band, believed that they could go all the way. McGuiness really projected that, the band really respected that, and that’s why they worked together as a unit for many, many years.”

As for their music…

“Well, I’m from Jamaica,” Blackwell states. “I’m bass and drum, this was more high frequency. It was great but it wasn’t something that grabbed me particularly.”

Chris Blackwell and Bono at the London launch party for Achtung Baby in 1991. Island Trading Archive.

Advertisement

Blackwell may be being slightly politic here. In the book he admits that, “I didn’t really feel the music – it wasn’t my kind of thing, too trebly, a bit rinky-dinky.”

“I could see that Bono was serious, “ he continues. “He just projected, the whole band projected with him. There was a sense that they would definitely make it.”

Despite this, there was some talk, around the time of the slightly disappointing October album, of not taking up the option.

“The head of Island Records at the time, who felt the record wasn’t strong enough, and one should probably pass, the second record when Bono lost all his lyrics. But I believed in them completely, it wasn’t what my particular music tastes were like, but I believed in them. They knew what they were doing and, as I say, they had someone who was going to get them there.”

After the third album War was a hit in 1983, the band decided to change direction and producer, calling on Brian Eno. Blackwell flew into Dublin to discuss it.

“I thought Jimmy Iovine [who did produce the live mini album, Under A Blood Red Sky and would work with the band again on Rattle & Hum] was the right guy but they wanted Eno and it wasn’t for me to tell them what to do.”

Advertisement

Blackwell did become a fan of their music as the band grew.

“Absolutely. With U2 you play their albums. Other bands, you played this single and that single, but with them you play their albums.”

Shore Leave

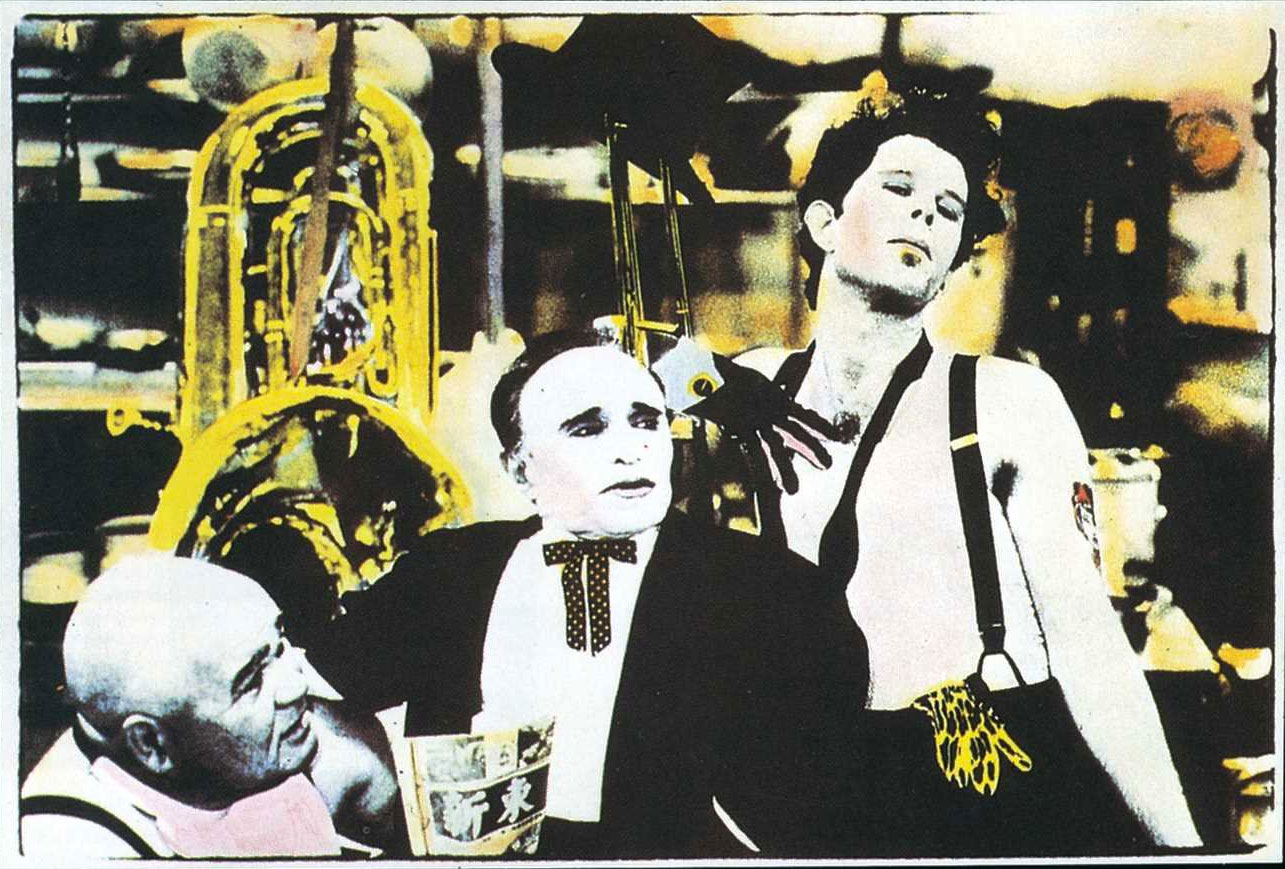

As U2 began to conquer the eighties, Blackwell also signed Tom Waits, a quintessentially Island artist. Waits had offered a new kind of album to Elektra/Asylum, who rejected it.

“I couldn’t believe you could refuse somebody who’s been around for a long time and knows his art form,” Blackwell recalls. “I guess the people running Elektra at the time felt they were not going to sell records of that kind of music. My interest has always been to get the best that the person can be doing. Everything doesn’t have to be huge.”

Blackwell was taking a chance. He didn’t hear the record until after he’d signed Waits. As great as Swordfishtrombones undoubtedly is, it is very different to what he had been at before.

Advertisement

“It was,” Blackwell laughs. “It was completely different, but it was unique. Nobody else sang like that!”

At the decade’s end, Spin magazine put Swordfishtrombones at number two in the greatest albums of all time, in between Dylan’s Blonde On Blonde and James Brown’s Sex Machine. Blackwell sees it as “the kind of record that’s never going to run out of steam, because it’s as much a great novel or a classic film as a record.” It’s the kind of thing Island have always been good at, releasing a record that may not sell a million straight out of the gate but whose reputation increases as time passes.

Involvement in the film business, in particular the failed Good To Go movie that attempted to document Washington’s Go-Go scene, a genre of music best exemplified by Troublefunk, left the company in financial difficulties, unable to pay money owed to U2 for one thing. Blackwell explained the situation and U2, rather than kick up a fuss, worked out a deal, getting 10 percent of the company and their masters back. Blackwell felt the moment had come to sell the label. “I thought, ‘that’s my time’,” he says now. In 1989 Polygram bought Island Records for close to $300 million – earning U2 what Blackwell estimates to be five times their missing back royalties.

He stayed on as the label’s chief executive but there were clashes with PolyGram’s CEO which ultimately led to his resignation and the end of his association with Island Records. Having a boss just didn’t suit him. “Probably,” he says. “I was spoiled.”

Before he goes off to enjoy the sunshine, Blackwell surprises me when I ask him to select one record he’s particularly proud of.

“Certainly one of my favourites is Marianne Faithful, the one about driving through Paris…”

Advertisement

‘The Ballad Of Lucy Jordan’?

“Yes. It’s really her voice and it tells a story. The lyric and her voice sort of cracking up, like somebody crying but not crying. There’s something emotional about it.”

To close, he sums up the ethos of Island.

“To open up a voice of this Island which I’d grown up in and lived in and love. That was really important for me. When it spread, I was able to have success in things that came out of England and America, but I was always really keen on Jamaica being in the loop because I just really love the country and the people. That’s been the main drive behind this.”

_______________

The Islander: My Life In Music And Beyond by Chris Blackwell with Paul Morley is published by Nine Eight Books