- Opinion

- 13 Jun 22

On Wednesday 8 June, Hot Press founder and editor Niall Stokes was presented with an honorary doctorate by the Open University. This is the draft text of what he had to say to the recent graduates of the university, who were there on the day...

There are moments when you really have to stop and think – and this is one of them.

Stop and think: what can I say to this splendid group of recent graduates that might actually mean something. Or that might, in some small way, help them on their journey forward into the great unpredictable future…

Stop.

And think.

Before you speak.

Advertisement

I want to begin by saying that it really is a great privilege to be welcomed to the stage here in Croke Park today, as the recipient of an Honorary Doctorate from the Open University. And to say thanks to John D’Arcy, who is head of the Open University in Ireland and to Dr Heather Richardson for her kind words. I am profoundly grateful.

The Open University is a wonderfully idealistic organisation which was founded back in 1969 with the specific mission of democratising third-level education in the UK, and making it accessible to all, irrespective of gender, class, age, creed, status or race. And it has since spread its wings to Ireland and elsewhere across the world, which is a very good thing indeed.

I think it is important to acknowledge the transformative importance of education.

It opens us up to the value of listening.

It makes us aware of how much we don’t know. It fosters a spirit of enquiry.

It enables us to go beyond the strictures of dogma and superstition.

It encourages us to ask: what do I believe in? Why? Does it make any sense?

Advertisement

For me, it has never been enough that something is handed down, that we are born into a particular place and therefore grow up under the influence of a given religion, or in a family that has always supported a particular political party.

We owe it to one another to take responsibility for what we say we believe in. And – if it doesn’t make sense – to start again, and think afresh and decide: what do I – what do we – really stand for? And how does that affect everyone else around me? How does that affect society?

In bringing learning to huge numbers of people, the Open University fosters that vital spirit of critical exploration. Long may it continue to thrive, in its enlightened, egalitarian mission.

TEAR UP THE RULE BOOK

I am also very grateful for the recognition of what we have achieved in Hot Press – as a team and as a collective – since the magazine was launched in 1977.

Ireland was a desperately conservative mono-cultural and largely inward-looking place at the time. “This is no country for old men,” William Butler Yeats had complained in the opening line of Sailing to Byzantium, in 1928. Almost 50 years on, that axiom had been turned in its head. Ireland was not a good place to be young then.

Economically, it was stagnant. Inflation was running at 18%. Unemployment was high. There was a deeply unhealthy relationship between Church and State. Censorship was rife. On this side of the border, contraception was officially available only to married couples – and, again, only if it had been prescribed by a doctor. Homosexuality was illegal. There was only one State-sanctioned broadcaster in Radio Teilifís Eireann – and an extremely conservative national newspaper industry. Popular music – or rock ’n’ roll – was largely dismissed as vulgar and commercial, and far less artistically important than opera, classical music or ballet.

Advertisement

And over all of this desperately murky cultural and political stew, the Troubles in the North – and the bloody atrocities which were being carried out on all sides during that nightmare period – hung like a dark and suffocating cloud. Sectarianism was like a cancer, gnawing away at our insides. At times, the whole sordid morass was enough to make you despair of people, of humanity...

But I knew – we knew – that we couldn’t let the prevailing darkness get the better of us. We couldn’t let bitterness take hold. We knew that there was – or that there had to be – a better way.

As a young man graduating towards adulthood, it was music that first made me aware of the fact that there really was another world out there, far beyond Irish shores, a world that was teeming with possibilities, a world of hope and opportunity – a world with the prospect of wild adventures to be undertaken, if only we could find our way to them. Or find a way of bringing them on home to us.

I remember hearing The Beatles and The Rolling Stones for the first time and it was like mainlining adrenalin. Seeing Bob Dylan singing ’Blowing In The Wind’ and ‘With God On Our Side’ in black and white on the BBC. Scrawling the name of the great black soul singer Otis Redding on a school copybook. Hearing The Supremes pleading: “Stop! In the name of love/ Before you break my heart… “

Lying in bed, on a holiday in Donegal, listening to Radio Luxembourg under the covers and hearing wah-wah guitar for the first time ever on ‘Burning of the Midnight Lamp’ by Jimi Hendrix and being utterly mesmerised and transfixed by where this music was coming from, by what is sounded like – other worldly! – and by where it was taking me, into another dimension entirely.

Throughout the 1960s – and increasingly over the final two or three years of the decade – there was a flood-tide of extraordinary creativity in music, with artists reaching across boundaries of time, place, cultural background, history and influence for inspiration. This creativity was allied to a new kind of curiosity, open-ness and ambition. That was where I wanted to find myself.

This was also the moment when modern communications started to make it possible for people – and young people in particular – all over the world to hear music from far flung places almost instantaneously for the first time.

Advertisement

Women started to claim their place at the forefront of this great musical ferment. Otis Redding had written ‘Respect’, but when Aretha Franklin recorded it in 1967 and turned it on its head, issuing the immortal cry “R.E.S.P.E.C.T – find out that it means to me”, it hit like a bolt of electricity. It was a moment of recognition. A clarion call for women all over the world.

Aretha Franklin

Things would never be the same again. And we would all be the better for it. Of that I had no doubt whatsoever.

Fundamental to all of this, of course, was a great and growing demand for freedom of thought and of ideas. And a burgeoning willingness to throw off the shackles of inhibition – of starched and buttoned-up control – that had marked post-War culture. In America, the Civil Rights Movement was on the march. The demand for Women’s Liberation was growing. And in 1969, the Stonewall Uprising marked a turning point in the battle for LGBTQI rights.

On this little island, here on the west of Europe, we were far from the epicentre of innovation, but this great explosion of musical and cultural experimentation had reached Ireland nonetheless. Van Morrison, Rory Gallagher, Philip Lynott and Thin Lizzy – and indeed dozens more – had taken up the mantle. But these Irish musical pioneers had all felt the need to emigrate. To go elsewhere to earn a crust.

The stranglehold exerted in Ireland by the dominant conservatism – and its creeping deference to old hierarchies – remained tight. An accelerating spirit of change – and an emerging feeling of liberation from outmoded ways of understanding the world – was taking hold in the US, the UK and across much of Europe. It was happening behind the scenes, and in the underground, in Ireland. But none of this was being reflected meaningfully in the media or in politics here.

Advertisement

Increasingly, through the 1970s, a generation had been faced with the stark choice: leave Ireland or set about changing it. Rock and roll music, in all its myriad forms, had blown our tiny little minds wide open, and as a result there was no way that we could simply sign up to the status quo that prevailed on this island at the time.

It was with all of this in mind that we started to think about launching a magazine.

That, of course, was my biggest mistake.

Niall Stokes in 1977

For the bunch of demented young idealists who worked feverishly on the first issue of Hot Press there were three inter-connected strands to what we set out to achieve.

– The first was to write about, highlight and celebrate the wonderful, artistically inspired, and creatively inspiring, music that was being made in Ireland – and abroad – by Irish musicians, songwriters and bands – and thereby to inspire more artists that would aim even higher

Advertisement

– The second was to produce a great, world class magazine that would give a platform to a different, more radical kind of journalism and writing – and that would also stand alongside Rolling Stone and NME and the other international counter-culture magazines that were shaking things up in the US, the UK and elsewhere.

– And the third was to do anything and everything we could to change Ireland.

We would tear up the rule book that was applied elsewhere in the media.

We would give writers the freedom to express themselves.

We would use the language of the streets.

We would refuse to delete the expletives.

We would place sex and sexuality at the heart of the agenda.

Advertisement

We would act as advocates for a progressive form of politics.

We would demand the separation of Church and State.

We would fight against sectarianism in any and every form.

We would resolutely oppose racism and prejudice.

We would support the equality agenda.

And we would challenge the gatekeepers who stood in the way of progress at every turn.

STRIVING TO MAKE THINGS BETTER

Advertisement

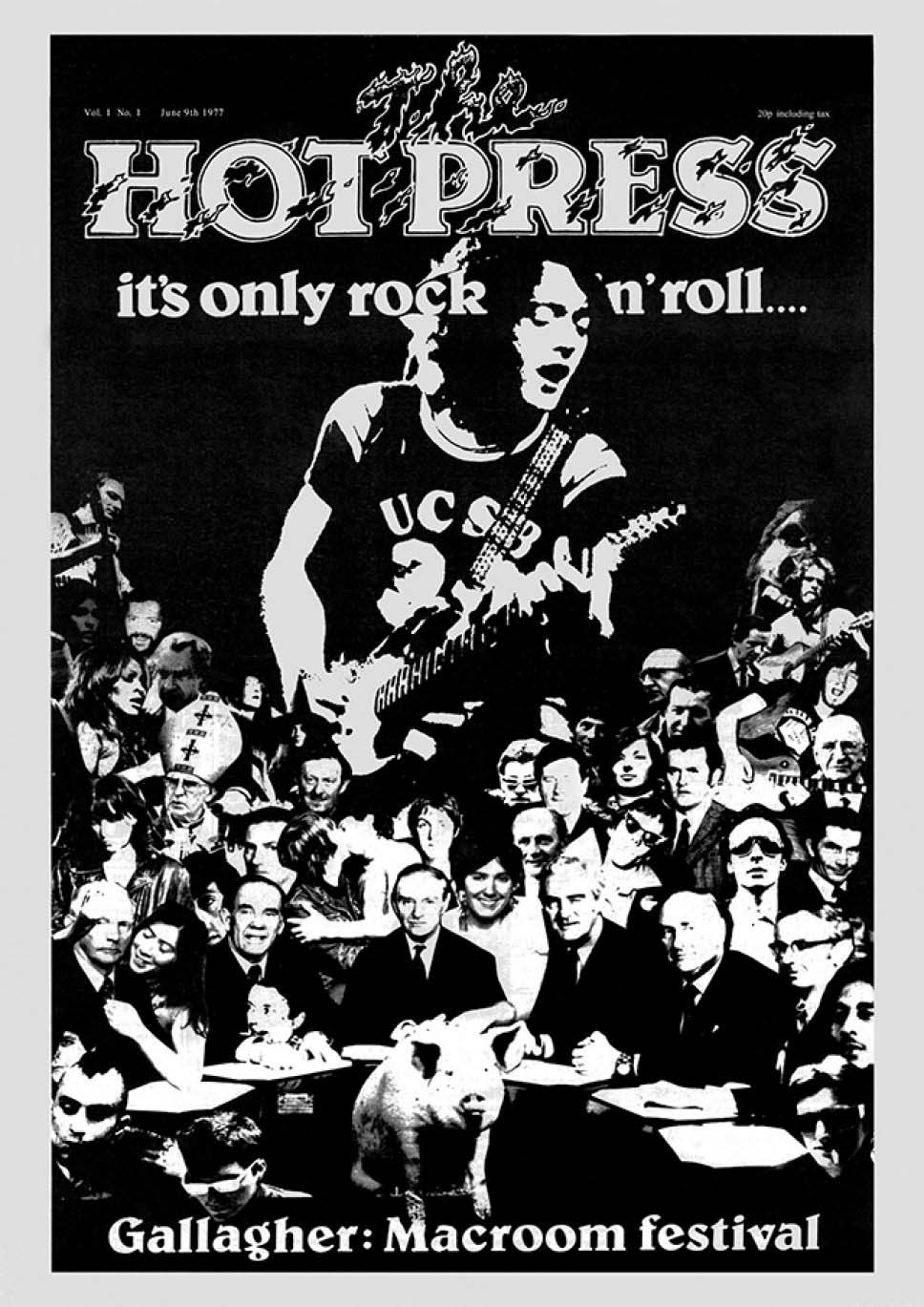

If you look carefully at the front cover of the first issue of Hot Press, you will see – among the rock n’ roll reprobates and the politicians brought together Sergeant Pepper style on that historic edition – right at the centre, lurks the figure of the then-Taoiseach Liam Cosgrave.

As Taoiseach, in 1974, the same Liam Cosgrave had, without any advance warning, walked across the floor of the Dáil to vote against a bill to make contraception officially available in Ireland. This was a thoroughly bizarre moment. The bill, which had been tabled by his own Minister for Justice Paddy Cooney, was an extremely conservative one, minimalist in what it would have permitted. But with the help of the Taoiseach – and another half a dozen or more government TDs – it was voted down.

Those TDs spoke out against what was then called “the permissive society.” They were, of course, resolute in their opposition to homosexuality – in their homophobia. So when the Gay Sweatshop theatre group came to Dublin in 1976, to perform in the Project Arts Centre, there was widespread outrage among the establishment political classes.

“Down with this sort of thing,” they cried, attacking it as “foul, filthy, stinking muck.”

And then they used their control of the public purse in an attempt to crush what we understood to be a legitimate expression of people’s sexuality and their sexual preferences.

By way of retribution for having hosted an openly gay theatre group, the members of Dublin City Council voted to withhold grant support from The Project Arts Centre. Even more disgracefully, the Arts Council followed suit, also withdrawing funding.

This is the kind of territory into which Hot Press emerged.

Advertisement

First Cover

If you look more carefully at that first front cover, just behind Liam Cosgrave’s head – and deliberately confronting his prejudice – you will see an image of two men kissing.

It was a statement of intent. We knew which side we were on. We were all for the permissive society!!

And we continued as we’d started. In our second issue, we put Joan Armatrading – a black lesbian artist who had come from the West Indies to Birmingham in England to live – on the cover.

From the very start, Hot Press was committed to the fight for equality. For inclusion. For an Ireland that would embrace all of its children equally. This was what I believed in. It was what my partner in crime, and co-founder of Hot Press, Mairin Sheehy believed in. But it was also what the Hot Press collective – what this group of young writers, and media activists, most of whom were recent graduates – believed in.

Most of whom were recent graduates – like everyone in the room here today.

Advertisement

Which brings us almost full circle.

Everyone here has achieved something marvellous. You have proven yourselves worthy of a Bachelors or a Masters degree. You have attained a level of learning – of knowledge – which is enormously impressive, and of which you are entitled to feel proud.

I am sorry that I have taken the scenic route to get here, but I am coming shortly to the thing that I wanted to say today. The thing that might just be useful.

Of course, none of what we have done, or do, in Hot Press, happens in isolation. Our experiences help to shape us. To one degree or another, we are products of our place and of our time. And this is as true of the young writers, designers and creatives who are working with us now as it was of the early adapters!

But we are not only that. When we started out, we were determined to have a dynamic relationship with Irish society. As I said, we really wanted to play our part in changing things. In bringing about a more liberal, open, compassionate, egalitarian society based on mutual respect, support, encouragement and commitment. One in which differences would not just be allowed for, but celebrated. And one which would always have at its heart a commitment to ever greater inclusion and ever more effective equalisation..

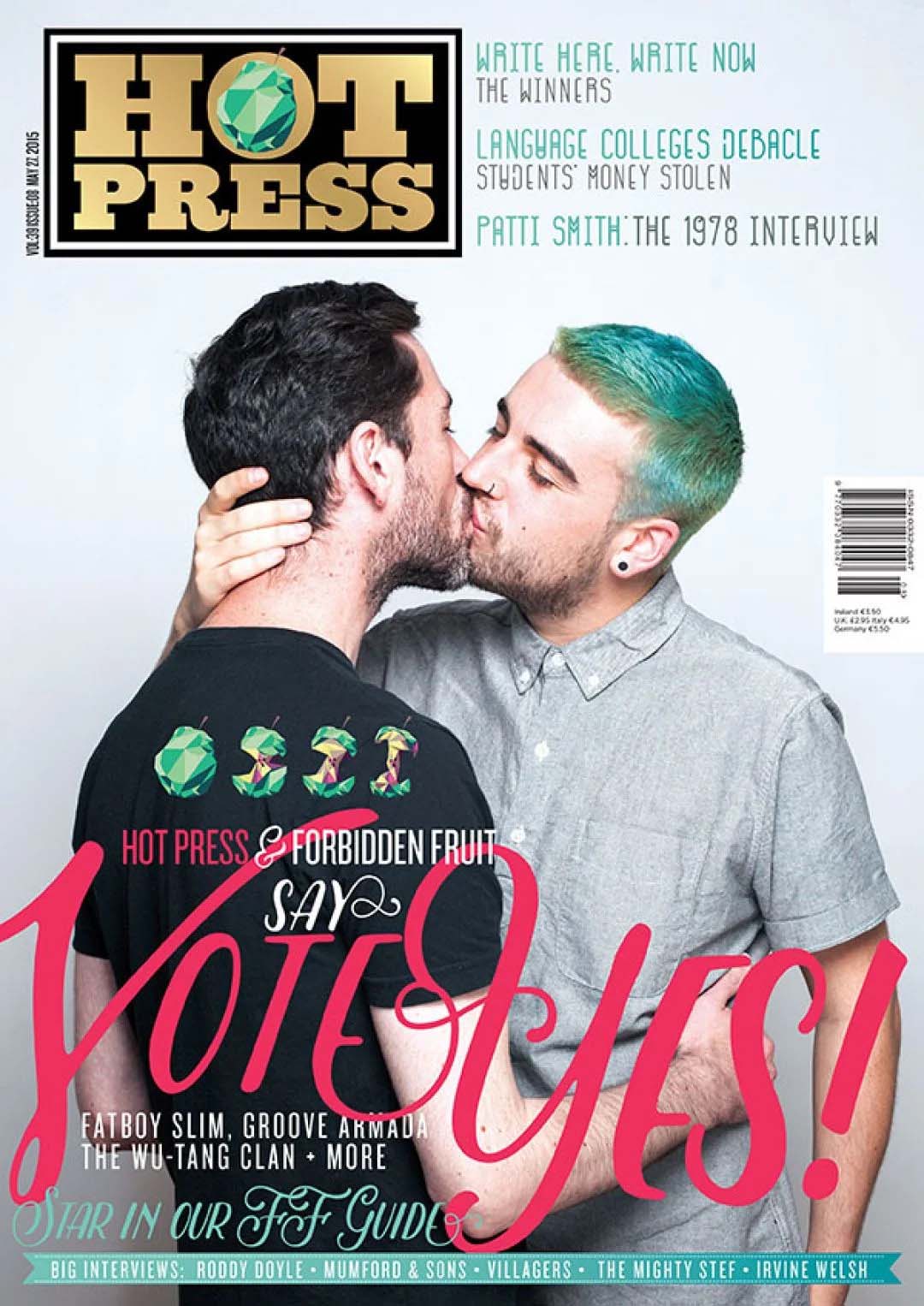

That, of course, is a permanent, ongoing struggle. But we are far closer to that ideal now here in Ireland, in 2022, than we were back in 1977. It took a long time, but it was enormously symbolic when – in 2015 – we were inspired to once again put a photograph of two men kissing on the front cover of Hot Press.

We were on the final run-in to the Same Sex Marriage referendum and we decided to create two covers for that issue and to split the print run 50/50. On one cover, there was a photograph of two men kissing. And on the other there were two women kissing.

Advertisement

No one – well, that we know of – decried it as “foul, filthy, stinking muck.” The referendum was passed by a huge majority. And an entire generation breathed an enormous sigh of relief. We had, finally, matured as a nation.

Of course, if you want to be part of a process like that – if you want to achieve things, if you want to make a business work, or a media enterprise sustain – you need ideas, inspiration, creativity, the ability to innovate and to take risks.

But you need something else too.

For us, it has never been about individuals.

It has been about wanting to make a collective contribution to the greater good to Irish music and Irish culture and everything that spreads out from that core fascination.

And we knew that to do this, we would have to be willing to work hard, to put in the time, the effort and the energy. We knew that it would require dedication. We knew that it would take commitment. It would take a willingness to stretch ourselves, and in doing so to get better. So that we could give more. And do more. And achieve more.

Advertisement

And so I would say to you finally today: what you have achieved in your studies is brilliant. But hopefully it will prove to be just, as Lou Reed put it, the beginning of a great adventure. A great adventure that will involve working hard and striving to make things better – not just for yourself, but for your family and your community and for everyone around you on this island of Ireland and beyond, in a spirit of generosity, inclusiveness – and love.

The future is yours. Make the most of every minute of it.

• Niall Stokes, editor of Hot Press, was bestowed with the honorary degree of Doctor of the University by the Open University in Ireland at a ceremony at Croke Park, Dublin on Wednesday 8 June. Read the full news story here.

The Message is taken from the new issue of Hot Press – available to pick up in shops now, or order online below: