- Opinion

- 02 Mar 22

Niamh Campbell: "Dublin became one of the poorest cities in Europe, then built itself up to be this new tech place. There’s no sense of stability in crashing and then renewing it"

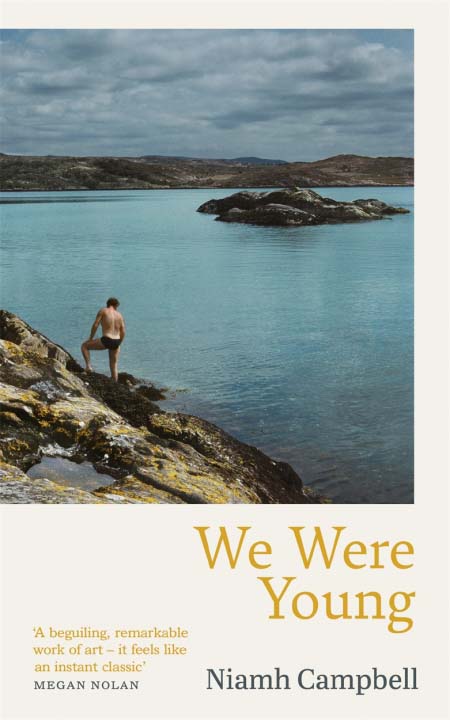

She enjoyed acclaim for her prize-winning debut This Happy. Now, Niamh Campbell’s follow-up novel, We Were Young, offers a compelling exploration of masculinity, trauma, and the lingering effects of the Celtic Tiger on Dublin city. Photography: Miguel Ruiz.

The last time I spoke to Niamh Campbell was in July 2020, just a few months after the pandemic began. Her debut novel This Happy was about to be released to serious critical acclaim, landing her on the list of emerging young Irish writers who were gaining impressive traction beyond their homeland.

Since then, the Dublin author was offered a lecturing position in creative writing at UCD, which she gladly accepted. Shortlisted for the An Post Irish Book Awards for This Happy, she also collected the 2021 Rooney Prize for Irish Literature along the way. Thus, Campbell experienced what really has been a stratospheric rise while effectively stuck at home.

This Happy is awash with Joycean prose and depictions of women’s interactions – often with older men – that are marvellously frank. 23-year-old protagonist, Alannah, engages in an affair with a married man. Six years later, she’s married someone else, but memories of the past return to torture her. In contrast, We Were Young’s leading man Cormac Mulvey seems to have succeeded in suppressing his traumas – with frustrating results for the women orbiting around him.

A photographer and fine artist, who has since turned to lecturing in (what was then) DIT, his non-committal sexual relations with women, and sometimes men, are painfully unbalanced. As the reader learns more of his past, including the tragic death of his brother Thomas and his mother’s mental illness, Campbell in turn addresses the issues – and the associated stigmas – which still plague Ireland. From its depiction of alcohol abuse, of the inadequecy of mental health supports, of the Magdalene Laundries, and of gentrification to the country’s failure to support the arts, We Were Young pulls no punches.

“I do think about whether the level of detail will translate to people who don’t live in this world, but I feel an artistic commitment to writing very honestly about Dublin as it is,” Niamh tells me. “Writing within the Anglosphere and being published in London, there’s sometimes an assumption that you should ‘code switch’. It’s this idea that you should iron out differences to appeal to a mass audience, and I find that vulgar. If you’re writing Dublin, you’re writing after Joyce. It’s not neutral to write about this place.

What Ulysses captured is that it’s a post-colonial city. That imperialist aftermath, and how it relates to today’s neoliberal era, is important.”

We Were Young has minute levels of exquisite detail, peeling back the pristine shine of the world of the arts to expose what lies beneath. In this way, Dublin is often portrayed within the shadow of evictions, multinational corporations buying up accommodation in bulk, hotel developments and blatant classism. There’s a ghost present that explores the burden of maternity for all women – pregnant or not – as a result of the Magdalene Laundries, zero sex education and the Repeal referendum.

“We Were Young was mostly written in 2019,” she resumes, “so a lot of it was experiences going on around me. I could probably go anywhere with it, but I’d like to be here right now. I want to be mixing at the heart of where culture is being produced. Dublin is a city with a very fraught sense of itself, and a lot of coarseness to it. It was the provincial city in which soldiers were garrisoned for 100 years.

“Overnight, it became one of the poorest cities in Europe, then built itself up to be this new tech place. There’s no sense of stability. They’re always crashing and then renewing it, which can be traumatic for people. When I came back after the 2008 crash, there was this sense of it being derelict again, like a sense of ruination had just returned. Then it pulls itself back up again. I express honesty by keeping the city as this slightly problematic zone.”

Niamh Campbell. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

Niamh Campbell. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.The novel opens with a theatre performance on the Magdalene Laundries, where audience interaction plays its own role. Cormac is immediately thrust into the narrative, faced with coffins and women scrubbing themselves down, seeking the exit as a means of escape. This scene foreshadows the way in which he looks to evade emotionally fraught situations, mostly with the women he sleeps with.

“He’s not conscious of the way in which he relies on other people for his needs,” Niamh explains. “The art events he goes to are usually about women’s suffering, but he’s not able to see it. He just finds it kind of annoying. I wanted to play with this idea that we were living through this moment of talking about the abuses that have gone on in Ireland, particularly gender relations. As I came back here from London, just before Repeal the Eighth began, this idea of what the State owed to women was in the air. There was this polite backlash from men in my life, who found this emphasis on women to be boring. It didn’t feel relevant to them.

“They weren’t able to see what this moment meant, so I wanted to look from the inside. Cormac isn’t a dislikable character. His purpose was to show a perspective – one with many blind spots. He needs to have people, and women especially, around him – but he doesn’t really return any of the favours. They expect some kind of loyalty or relationship from him but he considers himself to be detached. What he really is, is traumatised. He was almost created as an imaginary male version of me, when I pictured what freedoms I would have.”

A core issue We Were Young addresses is substance abuse – and, connected to this, suicide. The reader learns of Thomas, Cormac’s brother who died in what is perceived as an accident. He tragically fell from a balcony after getting high. The protagonist also has a complex relationship with his older brother Patrick, who struggles with alcohol abuse.

“Thomas’ death and the mother’s mental health are the first traumas in Cormac and Patrick’s lives, which set them on their particular life-paths,” Campbell notes. “They never opened the box, so it’s there as a symptom that’s never acknowledged. The loss of Thomas is what lies behind Patrick’s alcoholism, because he had to take up the mantle of the responsible eldest child with a family. Cormac and Patrick have this gaping wound, but men just get on with it. Their mother embodies that trauma.

“Thomas isn’t someone who stays in Cormac’s memories as anything other than this older brother who hurts him when he’s a child and acts wild. There’s this hint that perhaps Thomas jumped and had similar mental health issues to their mum. He also represents a violent explosion of masculinity that Cormac doesn’t want to inhabit. His brother was this destructive person who was a lot more conventionally masculine. He had porn under his mattress and joints in his bed and he burnt his own brother’s hands on the hob. They don’t really know the reality of his death.”

We Were Young doesn’t flinch in its examination of these themes.

“I came from a time where there were senseless deaths – by drugs or just behaviour that was completely mad – of men who didn’t have their trauma recognised,” Niamh continues. “Something about life didn’t fit with them. Stories like driving motorbikes off the road – it’s this unspoken history of male sacrifice. It’s the kind of culture that can’t process trauma.

“It relates, in a lot of ways, to how the nuclear family was experienced in a country with no divorce, no contraception for a long time, struggles with money and the idea of being incarcerated if you had mental health problems. All the taboos, all these layers of pain that are not really translatable. The risk of more loss is too big for Cormac.”

One of the novel’s most striking scenes features Nina, a younger artist who frequently engages in casual sex with Cormac. She steels herself to speak to him openly about her abortion, stating that if she became pregnant again, she would keep the baby.

“I wanted to stage these awkward encounters where you’re seeing things from a man’s perspective,” says Campbell. “We’re seeing a woman who is sharing something traumatic, and all Cormac can think about is getting away. He doesn’t like big emotions. He can’t face anything dark or serious. The complete catastrophe in his romantic life is a symptom of the matter he has bubbling up inside of him. But for her, she’s just not over her abortion and she wants to be taken seriously. She’s also kind of trying to be a ‘cool girl’ for men, seeking validation or acknowledgement.

“There is a blindness in people, particularly men, in comprehending the emotional weight of abortion,” Niamh concludes. “It’s seen as a moral question without thinking about the physical or mental effects of it on a person. Perhaps this failure to really show up emotionally is because men haven’t had to see it. It has been invisible. There’s maybe something to be said for it just being put out into the world more. However, for this to be the case, it once again seems to fall back on the women exposing themselves more, in order to educate.”

• We Were Young is out now, published by Hachette Ireland.

RELATED

- Opinion

- 17 Dec 25

The Year in Culture: That's Entertainment (And Politics)

- Opinion

- 16 Dec 25

The Irish language's rising profile: More than the cúpla focal?

- Opinion

- 13 Dec 25