- Opinion

- 27 Mar 23

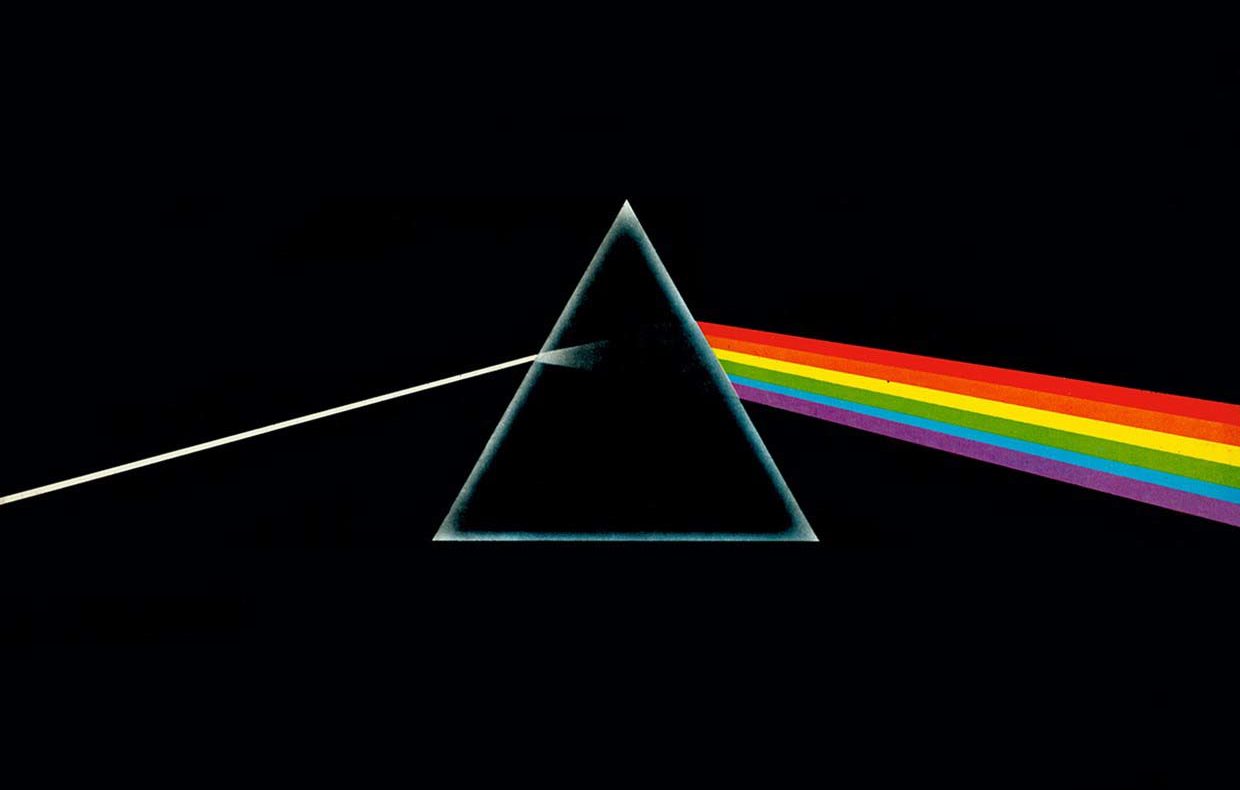

On the occasion of its 50th anniversary, the tributes have been flowing, in celebration of Pink Floyd’s most staggeringly successful record, The Dark Side of the Moon, released on 1 March, 1973. But there has been a glaring void in the coverage of this 45 million-selling blockbuster, with few acknowledging the way in which the album was shaped and influenced by the band’s original vocalist and leading light, the flawed genius that was Syd Barrett.

Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon is a landmark recording. Released on 1st March 1973, it remained on the US Billboard charts for 14 years. It has since shifted an astonishing 45 million copies, making it one of the best-selling albums of all time. Q magazine once theorised that because there were so many copies in existence, that it was possible that it is always on rotation somewhere on the planet. Maybe it still is.

Obviously, there are potentially countless artistic, cultural and theoretical strands to any discussion of one of the best-selling and most critically acclaimed albums of all time – the collective vision and artistic endeavour of then-current band members Roger Waters, David Gilmour, Nick Mason and Richard Wright being crucial. However, there is an entirely different way to enter the world of The Dark Side of the Moon, which is to exhume the ghostly imprint of the genius of the original Pink Floyd prime mover, Syd Barrett, on the album.

It is an approach which yields all manner of extraordinary questions. But to get to the heart of it involves a journey – or a trip even – not just down memory lane, though that is important, but deep into the realm of Englishness. I’m about embark.

You want to join me?

Advertisement

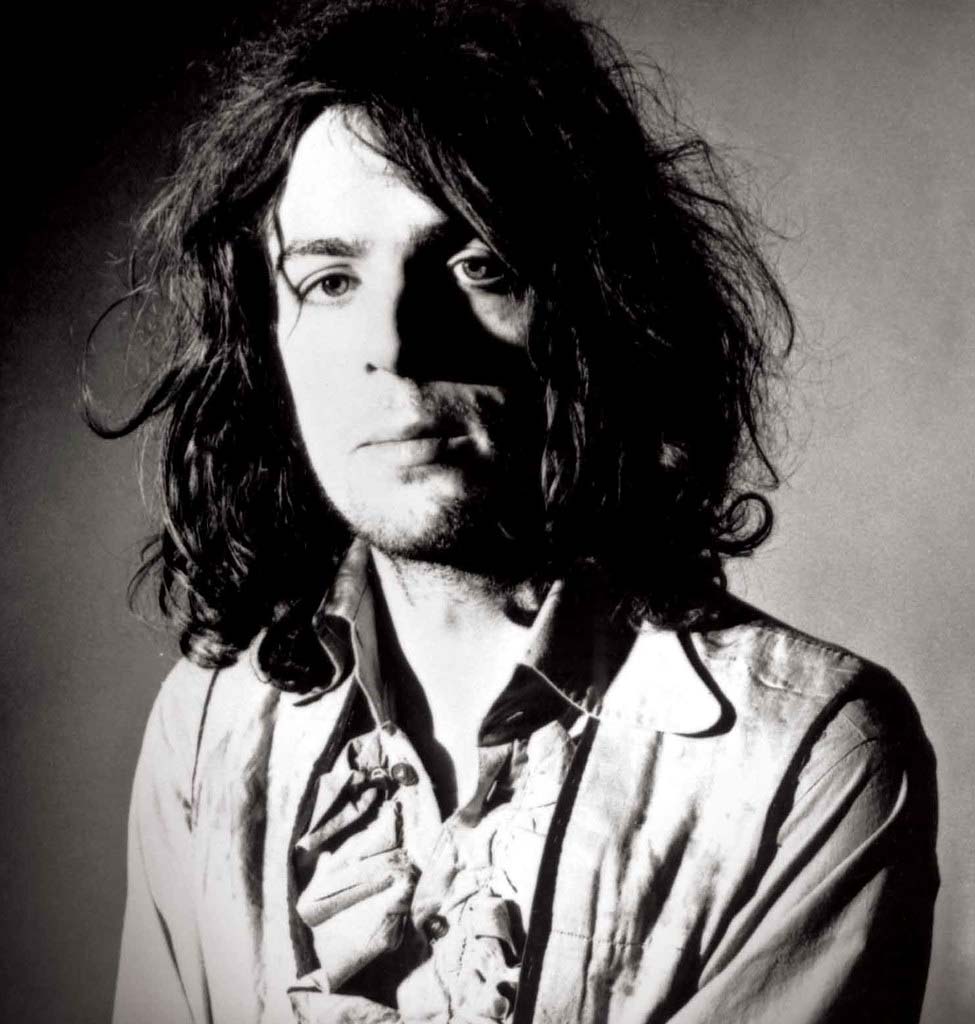

Syd Barrett.

Syd Barrett.*****************

Soon after the recording of their debut album, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, Syd Barrett left Pink Floyd, but through their subsequent albums – A Saucerful of Secrets, Atom Heart Mother, Meddle – Pink Floyd continued to be in hock to him. That much is seldom in dispute. Peter Jenner, one time manager of Pink Floyd, said of The Dark Side of the Moon, that although it was largely about Syd, it was the album where Pink Floyd escaped from Syd. On The Dark Side of the Moon, the received wisdom says, they became their own men.

This vital artistic leap was effected not – as might be imagined – by jettisoning the spirit of Barrett and what he represented musically and lyrically, but rather by understanding him; or to put it another way, by breaking his secret code for understanding how music can capture the hearts and minds of a mass audience.

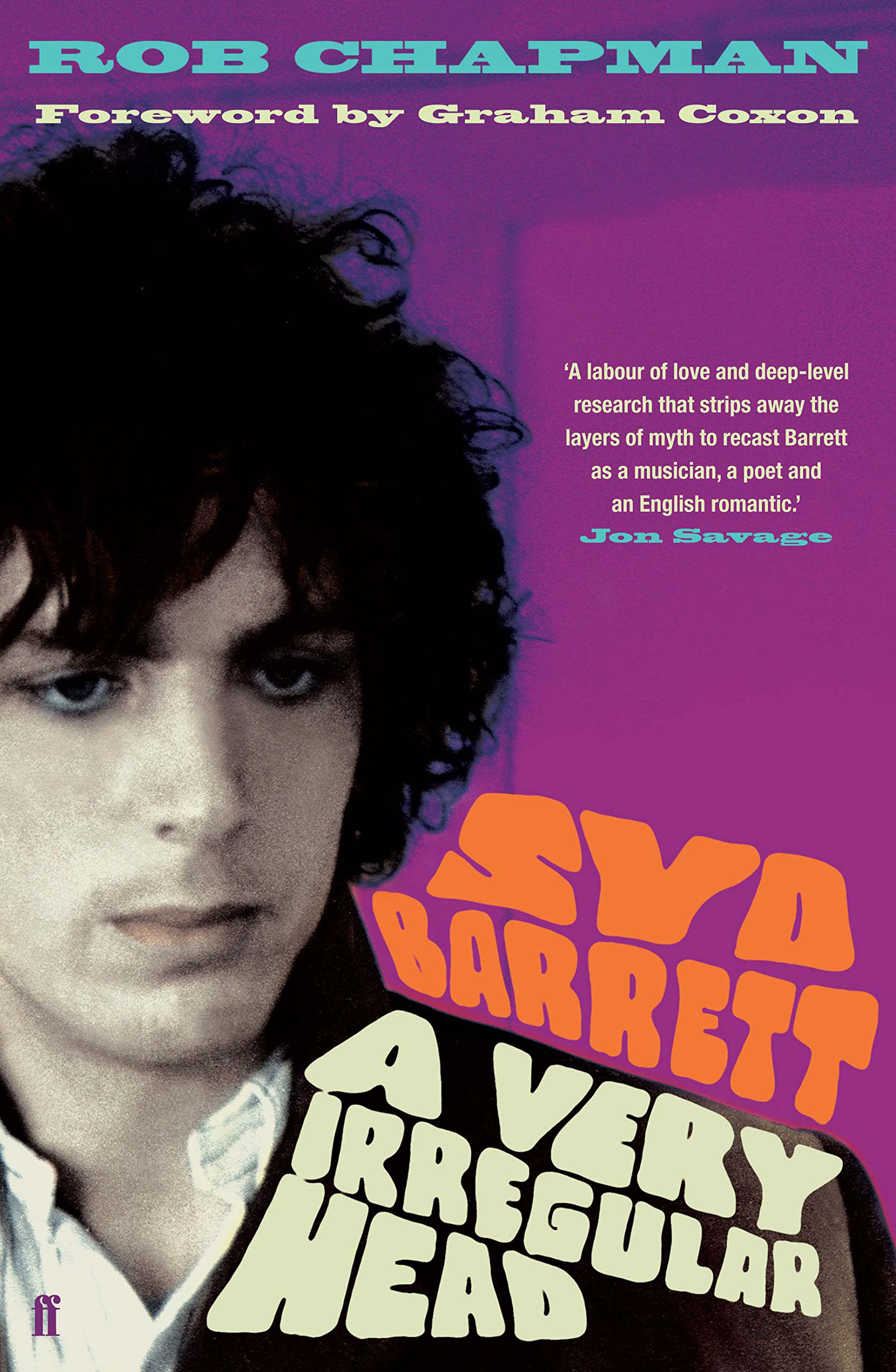

In the foreword to Rob Chapman’s book, A Very Irregular Head, the first authoritative Syd Barrett biography, Graham Coxon of Blur recalls his first musical encounter with Syd.

“I was seventeen and looking through ale smudged Christmas windows in Colchester, Essex,” he recalls. "The air smelled of mince pies and rang with the brassy roundness of the Salvation Army band. I was bewildered and happy – I had heard a song and felt trapped within it.”

That’s Syd Barrett, right there: he puts the hook in you and never lets up.

Advertisement

“The voice, the words, the sounds – all reassured and gave strange reference to my own identity,” Coxon elaborates. "The accent was my own, the childish rhymes from my own childhood and the music was expressive rather than technical – the rhythms primal. The sound went on forever, it was expansive with no strict structure and at times it would float away into chaos leaving your ears jumping to catch it like kite tails and your mind wondering who turned the gravity off. The music was dark and weird, peopled with freaky characters. A cave full of rabid geese pecked at your hair and aloof cats smiled straight through your secrets with milk-green blinding eyes. I had just discovered Pink Floyd, and Syd Barrett.”

Here, Graham Coxon very eloquently nails what so many people think when they first stumble across Syd – but most can’t find the words to describe the feeling.

Syd captured many and delivered them onto the rock ’n’ roll stage. David Bowie and Marc Bolan were in some ways begat by him; Robert Wyatt and Kevin Ayers were influenced by him, as were Roxy Music, Genesis, Andy Gill, Keith Levene, John McGeough, Will Sergeant, Robert Smith, Paul Weller, Roger Miller of Mission of Burma, Robyn Hitchcock, Colin Moulding of XTC, Daniel Ash of Bauhaus, Marc Almond, The Jesus & Mary Chain, The Mars Volta, My Bloody Valentine, Wire, TV Personalities, Primal Scream, Blur, Radiohead, The Melvins, Smashing Pumpkins, Soundgarden, REM, Mazzy Star, The Coral, John Frusciante, Richard Ashcroft, Daft Punk – I could keep going…

March 2023: The Dark Side of the Moon is turning fifty years old.

With that in mind, myself and my friend, songwriter and Barrett disciple, John Murry, decided to walk from London to Cambridge, the two geographical poles of Pink Floyd, and follow the charge of The Dark Side of the Moon.

It was to take three days, to walk from Battersea Power Station to Grantchester Meadows. The night before setting off, I planned to sleep in Camden Town. Wandering around, I dropped into The Underworld, where The Queers were playing. I supped a beer, watching them.

Advertisement

At dawn, I did a lap of Battersea Power Station, and started walking north. John was delayed, so we arranged to meet along the road. I whispered goodbye to the streets of London, before I changed my mind. I had lots of walking ahead of me.

***********************

Three days later – the evening before we would walk into Cambridge – we sat in our cramped quarters at the Red Lion Hotel in Whittlesford, watching Citizen Kane on the BBC, listening to the cars above us on the A505, zooming to beyond Six Mile Bottom and into Suffolk, wondering why on earth we were sat in cramped quarters at the Red Lion Hotel in Whittlesford at all.

The next morning, stood in the graveyard of St. Mary & St. Andrew’s Church, listening to ‘Time’ from The Dark Side of the Moon, we were pretending that things made sense. Experience taught us that this feeling would dissipate, that before long, as we trudged forward, we would invariably fall back on wondering what we were attempting to achieve. The clocks and bells of the church, that –pealing and clanging – have disturbed many a good sleep, sounded to wake the dead while Waters came from the speaker in John’s hand singing – “Ticking away the moments that make up a dull day/ You fritter and waste the hours in an offhand way.”

I contemplated the skeletons of generations of Whittlesford parishioners lying beneath our feet. Rousing ourselves, we trudged on: we were just eleven miles now from Cambridge.

In his visionary book, Edge of Orison, Iain Sinclair traces the steps of the great nature poet, John Clare, by following an epic three-day journey he made on foot in 1841 from an asylum in Epping Forest to Northborough, eighty miles north, in search of a lost love, Mary Joyce. Sinclair thinks of Clare’s epic walk, leading “Him back to an earlier self. To his wasted paradise.” Sinclair quotes Clare biographer, Jonathan Bate. “For Clare,” Bate wrote, "as for all poets in the Romantic tradition, writing was the place of remembering, of preserving what was lost: childhood, first love, moments of vision, glimpses of ordinary things made extraordinary by virtues of the attention bestowed upon them. Without loss, there would be no reason for poetry.”

Advertisement

Clare walked a zig-zag line from Enfield to High Beech, and then an angled sweep through Essex, Hertfordshire, Bedfordshire and Northamptonshire. In 1982, Syd walked a vertical line, as he left London and walked home to Cambridge. Both men were walking back to their memories of childhood, of place, of innocence: of a time and place, it might be speculated, before the Fall.

Barrett, Waters and Gilmour, all hail from Cambridge, a town that evolved from drained marshlands – The Fens – that had been reclaimed from the North Sea in the seventeenth century. It was a battle between land and sea which resulted in the creation of the best of English farmland, through which the fingers of the rivers Witham, Welland, Nene and Great Ouse creep towards the North Sea. The rich land in the area encouraged monastic communities to settle there, building grandiose cathedrals at Ely and Peterborough and leading to the expansion of Lincoln and Cambridge.

The fenmen, as those who lived in The Fens in crannóg-like houses were known, wandered into Cambridge on Friday afternoons, seeking ‘a penny worth of comfort’ in chemists and receiving laudanum, a tincture of opium to offset the lingering pains of malaria.

These characters from the English past must have fascinated young Barrett, Waters and Gilmour, living as they were out there, amongst will of the wisps, lost souls, ghouls and the like, in a place that enclosure could neither pin down nor cage.

It was a world that remained Tolkienesque, only the Fen folk knowing the paths and trails between bog and marsh from one point to another, where roads could not be straightened and boundaries could not be defined by uniformed hedging. When he got a little older, Syd explored and loved the surrounding countryside – cycling the old Roman road from Worts Causeway to Wandlebury, hanging out on top of the Gogs, watching the silent town below.

The river Cam runs along the back of the world-famous Cambridge colleges, flowing to the weir at the millpond where the lower river merges into the upper river which runs to Grantchester. In Chapman’s book, film-maker and friend of Pink Floyd, Anthony Stern, recalled halcyon Cambridge days – renting punts from Scudamore’s boat yards, put-putting down the Cam to Grantchester through the Albion countryside, on a river that flows past the backs of the gardens of academe, and King’s college chapel, nestled under Venetian arches.

Appropriately, ‘Brain Damage’, the penultimate track on The Dark Side of the Moon, is set there.

Advertisement

Animals album cover.

Animals album cover.***************************

In his final year at school, in December 1961, Syd Barrett suddenly lost his father to terminal cancer. Max Barrett cried out in agony, as young Barret tip-toed around the house on Hills Road. Syd’s world was torn apart – and perhaps, it was then, even at this early stage, that he lost Arcadia. You cal almost picture it: Syd – so often depicted as the golden child of 1967, that golden year in the golden decade of the 1960s – letting Arcadia flow through his hands.

The oft repeated story is that he turned his back on everything he had and everyone he knew, and returned to his family home in Cambridge to live as a recluse. I am not so sure that is the full story. Many people live their wild young years in a city and later return to the town in which they were born, to live a quieter life.

At his house on Hills Road in Cambridge, in the dark evenings, with his father gone, young Syd tuned-in to Radio Luxembourg to listen to American rock and roll. In his opinion Bo Diddley was the best of them. It is a view from which he never wavered. Inspired, he got himself a Number 12 Hofner Acoustic and with an amplifier built from a kit, jammed in his room with his friend John Gordon, calling themselves the Hollerin’ Blues.

Syd’s first official group, Geoff Mott and the Mottoes, saw Roger Waters sitting in on band practices: they played Bo Diddley and Jimmy Reed covers in Cambridge pubs. Roger and Syd dug rock and roll and danger, often hell-raising through the Fens at night on motorbikes. Roger recalls returning home on the train to Cambridge from a Gene Vincent gig in the Gaumont Theatre in Kilburn, and plotting the band they would put together when they were both in college in London. In the summer of ’63, Syd joined a blues outfit called Those Without, which later combined with David Gilmour’s group the Newcomers under the old moniker Hollerin’ Blues.

Advertisement

In 1964, Syd moved to London, studying Fine Art at Camberwell Art College. Rogers was studying architecture at Regent Street Polytechnic and the two Cambridge pals set up a band with two of Waters’ fellow students – keyboardist Richard Wright and drummer Nick Mason. They called themselves Spectrum Five, the Screaming Abdabs, the Megadeaths, the Tea Set – and eventually the Pink Floyd Sound, named after two of Syd’s blues heroes , Pink Anderson and Floyd Council. They were playing blues covers.

Over Christmas ’64, in a recording studio in West Hampstead, they cut a Slim Harpo number and three of Syd’s songs, including, ‘Double O Bo’, which Nick Mason described as "Bo Diddley meets the 007 theme." In the spring of ’65, they landed a residency at the Countdown Club in a basement off Kensington High Street. Performing five-hour sets, led the band to play long, improvised breakdowns between Bo Diddley and Rolling Stones numbers.

In the summer of ’65, Syd and his friend Storm Thorgerson, headed for the south of France in a beaten-up Land Rover, meeting David Gilmour in St. Tropez, busking Beatles tunes on the streets for change, and trying to avoid the police. They made their way back to Cambridge before the summer ended. Influenced by the outfit AMM, and the free jazz of John Coltrane, Syd began using his guitar in the slide position with an Echo unit and his Zippo lighter as a plectrum, to produce sound effects rather than melodies. Pink Floyd’s future manager Peter Jenner recalls seeing them for the first time, in June ’66 and being blown away by the band and their accompanying light show which he found mesmeric.

An excellent resource for following the development of the band from R&B covers to their original psychedelia is the album – The Early Years 1965-1967 Cambridge Station that forms part of The Early Years, the larger box set covering the genesis of the band up to the recording of The Dark Side of the Moon. But there is, of course, more to this story than meets the eye.

Pink Floyd.

Pink Floyd.*****************

Advertisement

I was sitting on the front porch of my wigwam-style bunkhouse at the YHA Lee Valley Hostel at Waltham Cross. There were four more huge bunkhouses, each capable of sleeping twenty souls, there. All were empty. I was reading Orhan Pamuk describing hüzün – the idea that all citizens of Istanbul share a sadness that comes from living amid the ruins of a lost empire. I wondered could this be related to a theme that pervades much of the Pink Floyd canon.

I watched the warm May sun disappear and then sought sleep listening to football scores from across the country, thinking of Derrida’s hauntology concept: Marx haunting Europe from his grave – forever. The loss of Empire must prey on the mind, impinge on choice.

Dawn woke me. I showered, dressed and walked out of the hostel. There was ne’er a sinner to be seen. I continued along the River Lea Navigation, both river and canal, over the Kings Weir, planes dipping down into Stansted Airport. A grass snake swallowed a frog, a water vole plopped into the water.

At Cheshunt, I continued on to the New River, where I came upon an old hippie named Fred taking the morning air, and we got to chatting. He was up from Brighton, clearing a flat he owned: he'd had the same tenant since he had moved down south 20 years ago. He told me that he once worked for Thames Waterways, explaining that the New River had once been the source of all London’s drinking water. Fred said it was nice to meet a fellow human being, as there were not many of us around these parts. We said our goodbyes and moseyed on.

It was mid-afternoon when I arrived on the outskirts of Bishop’s Stortford. I dozed in a glade, woke starving, and tramped the rest of the way. In a diner, I ate a chicken burger and chips like a savage, the staff watching me. I crashed for a few hours in a room on Hadham Road and then walked to a park with fairground attractions and met John Murry who’d finally arrived from Brighton. We sat until long after dark, talking about Syd Barrett’s enduring influence on Pink Floyd.

As with John Clare before him, Syd appeared to go beyond merely recalling a lost Albion: he wished to recreate it, to step into it, to live there. Over an astonishing six months, he wrote most of The Piper at The Gates of Dawn – the title, taken from a chapter in Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows – in his top floor eyrie on Earlham Street in Covent Garden, overlooking Charing Cross Road and Shaftesbury Avenue. That record was derived from a mishmash of influences – fairy tales, folklore, hallucinogens, nature, abstract art, sex, romance, Indian mystics and Cambridge. The album dovetails snugly with Grahame’s transcendentalism and pantheism, his symbolism of the wild wood, protracted childhood and a lost Arcadia.

In November 1967, Pink Floyd went on an American tour to promote The Piper at the Gates of Dawn. None of the band particularly enjoyed the tour, but Syd in particular was visibly struggling. However, upon their return to England, instead of resting, the band were sent around the UK with six other groups for a sixteen-date package tour, playing two shows a night. It was one of the last of the great Sixties package tours - Pink Floyd, Jimi Hendrix, Move, Nice, Amen Corner, the Irish band Eire Apparent and Outer Limit were on the bill. Each show lasted just two hours. Hendrix got thirty minutes. On one occasion, he went over his allotted time by a minute and the promoter bizarrely threatened to throw him off the tour.

Advertisement

Syd wore out his copy of the Stones’ 1967 album Between the Buttons: it was quintessentially English and so too was Syd. Even during his final session with Pink Floyd, recording ‘Jugband Blues’ – when terrifyingly, he realised what was happening to him, that he was descending into madness – he retained a stiff upper lip and a clipped politeness. “It’s awfully considerate of you to think of me here,” he sang, "And I’m most obliged to you/ making it clear that I’m not here/And I’m wondering who could be writing this song.” That session also included ‘Vegetable Man’ and ‘Scream Your Last Scream’: the titles speak for themselves.

Syd Barrett left Pink Floyd – but arguably only in body.

****************************

In Storm Thorgerson’s accompanying video for ‘Shine On You Crazy Diamond’ – a song that was originally released on the album Wish You Were Here in 1975 –for the Pulse live show in 1994, an actor depicting Syd is shown wrestling in the water with his doppelgänger: one drowns, so the other can live. It is the myth of Castor & Pollux, those twin half-brothers in Greek mythology. One was immortal and the other mortal. But the mortal one appealed to the gods and it was decided that they would spend one day in two among the gods, the other in the Underworld. John Murry, walking into Cambridge, observes that “Syd is both Castor and Pollox.” I get what he means.

In July 2005, Syd was around his nephew’s house for a family dinner. After the meal, they invited him to watch his old band Pink Floyd on TV, playing Live 8. It was the first time that all four of his old friends – Roger Waters, David Gilmour, Rick Wright and Nick Mason – had played together in twenty-four years. Syd declined, choosing instead to go home and do some gardening. The last time he had seen Pink Floyd play, was watching them alone, just another member of the crowd, introducing The Dark Side of the Moon at the Rainbow Theatre in Finsbury Park in February 1972. The following years would see Syd’s old band become world famous, while apparently he chose anonymity.

Kris Di Lorenzo’s article in Trouser Press, February 1978 titled Syd Barrett: Careening Through Life was arguably the first piece to concentrate on the talent of Syd and not the hashed-out caricature of him as a loony tune. She opened with this:

Advertisement

“You all know who Syd Barrett is even if you think you don't. Without him there would have been no Pink Floyd. Barrett dominated the band during their first years, writing most of their material, singing lead vocals and playing lead guitar. He left the band (or the band left him) for reasons of mental health, and in 1970 with the aid of his replacement in the Floyd, David Gilmour, recorded two solo albums: The Madcap Laughs and Barrett. Syd then performed with Stars, an ensemble in the Cambridge area, but left them after three gigs and virtually vanished from the public eye.

"For the past five years Barrett has generally been written off as an acid casualty, but more often lamented as a musical visionary whose interior landscape became too disorienting for him to handle. Some of the stories one hears about Barrett are disconcertingly true, others only sound like Syd, but most of his acquaintances express the same conclusion: intuitive and fragile, Barrett was a unique talent and an erratic mind on the edge of a different type of existence – as well as a man who indelibly affected those who came into contact with him.”

Di Lorenzo described Syd as an artist immersed in jazz, blues, jug band music and Eastern music – yet, his guitar playing was original, experimental, but raccessible. Di Lorenzo expresses this differently.

“No technician a la Eric Clapton, Barrett simply knew his own particular instrument well and pushed it to its limits. Compared by critics to Jeff Beck, Lou Reed (in his early Velvet Underground days) and Jimi Hendrix, Barrett lacked only the consistency to match their achievements. His trademark (and Achilles heel) was sudden surprise: trance-like riffs would slide abruptly into intense, slightly offbeat strumming ('Astronomy Domine'), choppy urgency gives way to powerful, frightening peaks ('Interstellar Overdrive'), harmless lyrics skitter over a fierce undertow of evil-sounding feedback and menacing wah-wah ('Lucifer Sam'). Stylized extremes made Barrett's guitar the focus of Floyd's early music; his instrumental mannerisms dominated each song even when Syd merely played chords.”

Pink Floyd

Pink FloydDiLorenzo points out, that unlike Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page or Clapton, Barrett borrowed no licks from the blues.

Advertisement

“Barrett's song writing genius,” she adds, "was original and extremist as well. His singing was highly stylized; obscure chanting vocals, high-tension verses and explosive choruses alternating with deadpan storytelling and hypnotic drawls. He utilized fairy-tale technique, surrealistic juxtaposition of psychedelic detail and plain fact, childhood experience and adult confusion. Like the Beatles, Barrett combined dream imagery and irony with simple, direct tunes, strong, catchy melodic hooks with nonsense rhymes and wandering verses that sound like nothing so much as what goes on inside people's heads when their minds are running aimlessly.”

Syd’s signature remained on Pink Floyd records throughout the 70s and 80s, including the behemoths The Dark Side of the Moon and The Wall. Di Lorenzo is emphatic on this point.

“The dramatic mixes Syd applied to the Floyd's early recordings,” she explains, "are now magnified by 16-track studios but employ the same technique: whole walls of sound rocket from one side of the room to the other, the guitar careens in and out of different speakers, submerged speech and incidental sounds chatter beneath instrumentals; their use of sound as an emotional tool is absolutely Barrettonian.”

It is some statement. I happen to believe that it's true.

********************

Back in the Whittlesford churchyard, we listened to the last words of ‘Time’: “Far away, across the field/ The tolling of the iron bell/ Calls the faithful to their knees/ To hear the softly spoken magic spells.” Pastoral and rooted in England it is – as Di Lorenzo might describe it – very Barrettonian. You can hear Syd singing those last lines about the magic spells of religion: not so iconoclastic, perhaps, more Larkin’s Church Going, more comforting.

Much of The Dark Side of the Moon refers to Syd but abstractly. ‘Brain Damage’, on the other hand, is Roger Waters directly singing about – and to – Syd Barrett. “The lunatic is on the grass,” he sings (and yes, it is a pun), referring to those halcyon days on the green beside the River Cam across from King’s College– “Remembering games/And daisy chains and laughs”. It is all achingly poignant. “And if the dam breaks open/many years too soon/And if there is no room on the hill/And if your head explodes with dark forebodings too,” Waters sings. He goes on to tell Syd to meet him where he is “On the dark side of the moon”, if he –Roger – fails to compete with The Beatles or goes mad. Indeed, when Waters sings, “And if the band you’re in starts playing different tunes,” it is difficult to know who is singing to whom, an ambiguity which is compounded by the next line: “And there’s someone in my head, but it’s not me.”

Advertisement

‘Eclipse’ finishes the album with Waters reflecting despairingly: “And everything under the sun is in tune/But the sun is eclipsed by the moon.” It is left to Abbey Road Studios doorman, Gerry O’Driscoll – he’s from Ireland – delivering the final words: “There is no dark side in the moon, really. As a matter of fact, it’s all dark.” So, the curtain falls on The Dark Side of the Moon with the moon itself. Yet, the album is light years from the space rock tag that Pink Floyd had been mislabeled with.

On the face of it, the band had freed themselves from the esoteric psychedelia of Syd on The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, replacing it with Roger’s direct, uncomplicated language. However, both albums criss-cross on common or related themes: curiosity in exploring self; realisation of the quicksilver nature of youth and the wistful remembrance of it; the push and pull of a person’s hometown; willingness to experiment with sound; addiction to experimentation; the gelling of external nature with inner psyche; a child-like interpretation of the world that is derived from undertaking psychological journeys that most adults shirk from; the joy of immersing oneself in sonic assault; the propensity to question societal axioms; the creation of dreamscapes that punch holes in the stated wisdoms of reality - and so on.

After all, the lyricists of each album, Syd Barrett and Roger Waters, were childhood friends, adolescent co-conspirators and artistic collaborators, so, the fact that there is so much crossover between the two should not be surprising. Perhaps, the thing that is most important in both men’s art, is the realisation that contained within each person is the ability to make a heaven of hell and a hell of heaven. Above all else, The Dark Side of the Moon champions our common humanity, and the sense that we are each so much a part of one another, that we need to begin to recognise ourselves in one another.

Roger Waters from Pink Floyd in 1987 by Willie Christie.

Roger Waters from Pink Floyd in 1987 by Willie Christie.********************

In the winter, after leaving Pink Floyd, Syd Barrett drove his Mini through England, travelling to far flung beaches and desolate marshes, perhaps seeking the soul of Albion. His subsequent solo albums looked back, seeking lost loves and places; and they looked inward, carefully documenting his splintering self. Eventually, he returned to Cambridge, living the kind of life that most of us live – and in doing the most ‘normal' things, he became an object of fascination, more so than any of the rest of the band who had become world famous rock stars. The man who can sup at the table of the gods, but decides to do what mere mortals do, is often adored more than the gods themselves.

Advertisement

Myself and John Murry had a swift ale at the Fort St. George and then walked down to Cambridge Junction to watch that other great, somewhat eccentric English songwriter, Peter Doherty. He was performing The Fantasy Life of Poetry & Crime, his most recent album, on which he collaborated with French songwriter and composer Frédéric Lo.

Doherty, like Syd, is a creator of his own mythology, his own parallel world, which he can slip in and out of. He sings of a lost Britain, or a never gained Britain. Syd’s sister Rosemary, once described his psychedelia as being a version of the classical music of Stravinsky or the jazz of Charlie Parker and Thelonious Monk – all artists whom he greatly admired. Peter Doherty’s romanticism is a version of Chatterton (he used Henry Wallis’ painting of the poet for his Babyshambles Shotter’s Nation album cover), or Coleridge. As much as his persona influences his art, his art influences his persona.

Peter Doherty finished his set with ‘Salome’, a song that alludes to the wicked stepdaughter of Herod Antipas, he who was involved in the executions of John the Baptist and Jesus of Nazareth. “And from the flames appears Salome,” Doherty sings in that marvellously flawed voice of his, "I stand before her amazed, as she dances / and demands the head of any bastard on a plate.”

We went for chips and ate them standing up, looking out on a quiet part of Cambridge on a Saturday night. I was thinking of Salome dancing for the head of any bastard on a plate and Gerry O’Driscoll saying – “there is no dark side of the moon, in fact it’s all dark.”

Thank the sun, moon and stars for the illuminating poets who think differently despite the risks...

The new issue of Hot Press is out now, starring The Edge.

![Minister James Lawless: "How do we have two different rules [for alcohol and marijuana]?" Minister James Lawless: "How do we have two different rules [for alcohol and marijuana]?"](https://img.resized.co/hotpress/eyJkYXRhIjoie1widXJsXCI6XCJodHRwczpcXFwvXFxcL21lZGlhLmhvdHByZXNzLmNvbVxcXC91cGxvYWRzXFxcLzIwMjVcXFwvMDRcXFwvMDMxNzA1NTZcXFwvTWluaXN0ZXItRURVLWJ5LUFSLTI2LmpwZ1wiLFwid2lkdGhcIjpcIjMwOVwiLFwiaGVpZ2h0XCI6XCIyMTBcIixcImRlZmF1bHRcIjpcImh0dHBzOlxcXC9cXFwvd3d3LmhvdHByZXNzLmNvbVxcXC9pXFxcL25vLWltYWdlLnBuZz92PTlcIixcIm9wdGlvbnNcIjp7XCJvdXRwdXRcIjpcImF2aWZcIixcInF1YWxpdHlcIjpcIjU1XCJ9fSIsImhhc2giOiI5Nzg2MDBhOGZkZTdmZjcwMGM3ZDE5MDdkZjhlYmE1MmQ3YjAzZjMwIn0=/minister-edu-by-ar-26.jpg)