- Opinion

- 14 Apr 23

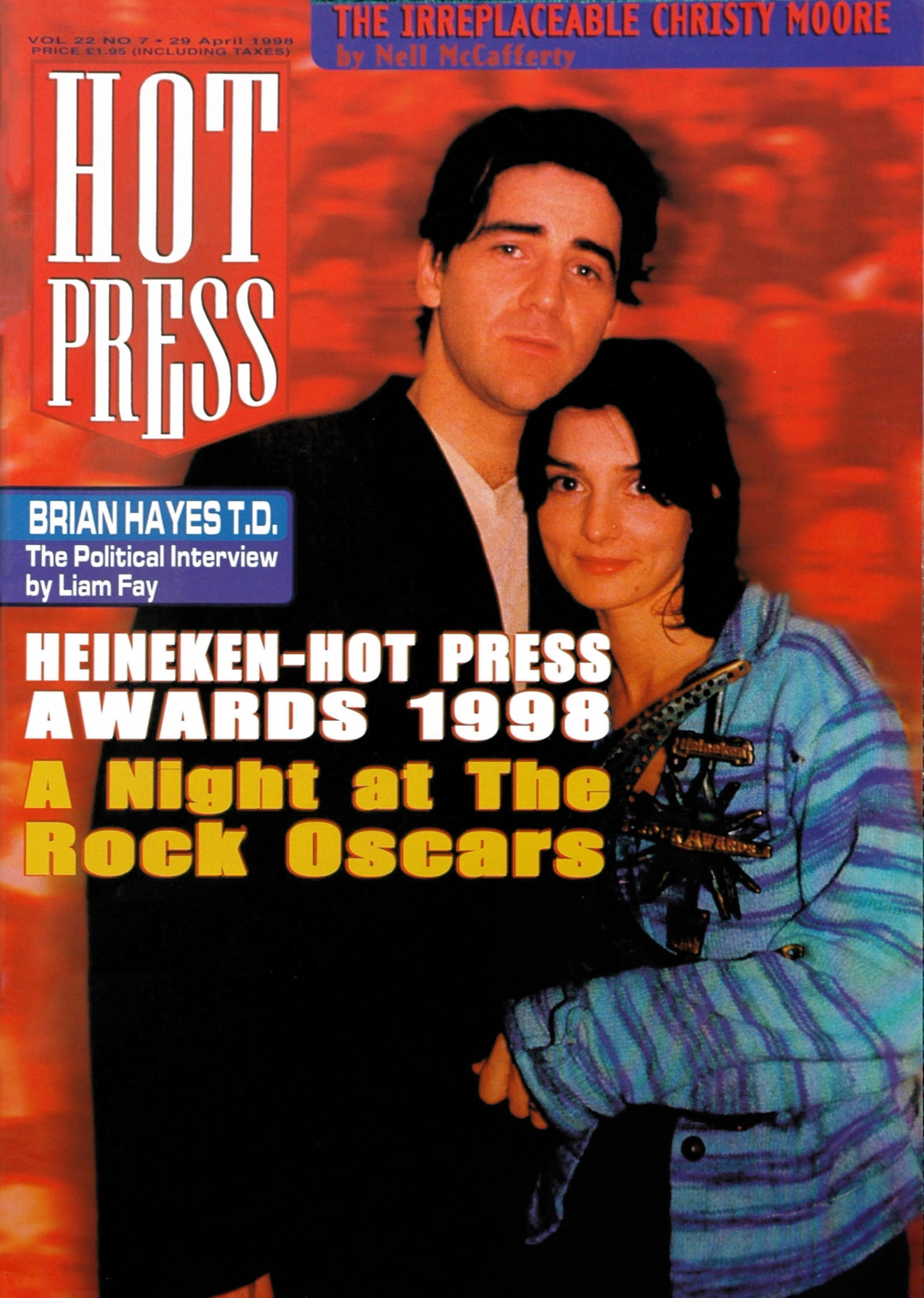

25 years ago, when the Good Friday Agreement was being signed, Hot Press was in the process of planning its annual awards night in Belfast. Though the political landscape has seen many ups and downs since, a fragile stability has endured in the North. As we seek to maintain peace through the current fraught period, we need to remain more vigilant than ever...

It was a strange feeling, revisiting those old articles, published in Hot Press back in April 1998, about the moment the Good Friday agreement was signed. We were in Belfast for the Hot Press Awards that week. There had been a sense over the previous few months that perhaps history might indeed be in the making. And so it turned out, as the reams of coverage in newspapers and across all media last weekend re-confirmed...

We were in our own bubble back then, setting out to make history of a different kind. We had taken the Heineken Hot Press Awards to Belfast for the first time the previous year – it was widely proclaimed a marvellous success and we’d had a ball. The stakes felt higher second time around, however, and so we wanted to deliver a brilliant cast, add a quota of surprise guests into the equation, and instigate some tasty musical collaborations. We wanted the musical extravaganza planned for the BBC studios to go down in history. And we threw ourselves energetically into making it happen.

It is hard to convey to anyone on the outside just how much goes into putting an event of that kind together, especially when you live and breathe it, the way we did in Hot Press (while also having to go about the day job of producing a new issue every fortnight); but what was especially gratifying was that our do-or-die approach (with an optimistic emphasis on the ‘do’ part!) was matched by Mike Edgar, Stuart Bailie and the rest of the gang in the BBC.

Together, we decided that no stone would be left unturned. Every potential opportunity would be hunted down feverishly. We’d deliver a magnificent show. Nothing less would do.

That’s the way we have always approached things in Hot Press. But there was an added dimension on that particular occasion. For us, and for Mike, it was important to make a bold statement in behalf of the musicians of Ireland. Hot Press had always seen what was happening north of the border musically as of equal importance to what might have been going on in Dublin, Cork, Galway or Limerick. Travelling to Belfast with the Hot Press Awards was a way of affirming that unshakable belief in our Northern brothers and sisters.

Advertisement

A GUNMAN ON THE LOOSE

We knew that, historically, music had been an arena in which people moved freely, most of the time, beyond the dysfunctional, tired, old sectarian fault-lines. Gary Moore may have come from a so called Protestant or Loyalist background in East Belfast, but that didn’t matter a damn when he arrived in Dublin to join Skid Row, plugged in his Gibson Les Paul and made a glorious noise. Nor was religious affiliation of the slightest concern when Rory Gallagher moved to Belfast and based himself there, when his band Taste were starting to make real waves.

Rory never lost that particular, non-sectarian rock ‘n’ roll faith. Throughout the 1970s – long after the Troubles had erupted, and violence on the part of the British State and paramilitary groups alike, saw people being butchered, maimed and brutalised on an appallingly regular basis – fans of Rory left any allegiances they might have been assumed to feel behind, as they travelled to the Ulster Hall to see the G-man in action. Music could be above all forms of sectarianism. Most of the time it was.

It never occurred to me to see Van Morrison and his marvellous lyricism as anything other than Irish. In almost every respect, we felt closer to him; to the Portstewart guitar genius Henry McCullough; and to The Undertones and Stiff Little Fingers, when their time came, than to the country, showband and cabaret crews who still dominated music in much of rural Ireland.

Not that everything had been entirely rosy. Far from it. In ‘Down At The Border’, the original Eyeless, a three-piece involving me, my brother Dermot, and Garry O Briain had written a song about it. “Down at the border,” it opened, “We met a gunman on the loose/ Followed down by an English convict/ Just out of the calaboose/ Two rustlers, pig smugglers/ And a tourist or two/ And then there was me… and you.”

Later in the song, the gunman shoots the convict “over something that he said.” There really was a surreal aspect to it all, like a magic mushroom trip gone horribly, murderously wrong. And then, for musicians, it got far worse entirely.

Advertisement

The brutal massacre of members of the Miami Showband, on July 31st, 1975 involved breaking a kind of sacred taboo, which had guaranteed musicians the freedom to travel across the border without fear of being ambushed. It poisoned the atmosphere and put an almost complete stop to local musicians from South of the border travelling North to play. I had a more visceral sense than most of what had happened. Eyeless, now featuring my brother Dermot, Neil Jordan, Pat Courtney and Bryan McCann, in a five-piece line-up, had travelled North in May that year, to support John Martyn in Queen’s University, Belfast.

My partner Mairin, pregnant with our first child at the time, was in the van too, when we set out for home. A wrong turn took us into the vicinity of Keshfield, at 1am, and we experienced a scarifying brush with what can only have been loyalist paramilitaries. We were lucky to get to the benighted town of Portadown, where we stopped in the most open, visible location we could find, scrambling to find our bearings and chart a path back across to Newry.

We made it, but it might have been a prelude to what happened to the Miami – who had been one of the most popular bands on the showband scene for the previous decade and more – a couple of months later.

The van in which they were travelling was stopped on the way back to Dublin from a gig in Banbridge, close to the route we had travelled. Posing as British Army personnel, members of the illegal UVF, some of whom were also in the legal but irredeemably corrupt Ulster Defence Regiment, instructed the musicians to stand in line at the side of the road. The plan had been to carry out a fake inspection, covertly plant a bomb and send the musicians on their way. Some accounts say that the bomb would have detonated in Newry. Others think the plotters wanted the van to cross the border before it exploded.

A NIGHTMARE TWILIGHT ZONE

Fate – and the incompetence of the UVF – triggered events in an entirely different direction that night.

While it was being installed under the drivers seat, the bomb went off, instantly killing two of the UVF members, Harris Boyle (22) and Wesley Somerville (34), whose bodies were blown to kingdom come, landing in blackened stumps across a wide area. Somerville’s arm was found some 100 yards away from the scene, pathetically emblazoned with a tattoo that said “UVF Portadown”. The members of the Miami were also blown away, into the adjacent field, but they were alive still, one and all. The UVF thugs panicked, gave chase and shot dead three members of the Miami – lead singer Fran O’Toole, trumpeter Brian McCoy, and guitarist Tony Geraghty. They thought the others were dead too.

Advertisement

The Miami – like most Irish professional bands at the time – were naturally and unselfconsciously anti-sectarian. There were two nominally Protestant musicians in the band, Ray Millar and Brian McCoy, both of whom were from Northern Ireland. Brian McCoy, in particular, was like a beacon of how music could potentially reach across every divide. From the small village and townland of Caledon in the south-east of Country Tyrone, he was the son of the Grand Master of the Orange Lodge in the county. You couldn’t get more traditionally Norn Iron Protestant.

Brian had close relatives in the RUC. His brother-in-law had been a member of the discredited and ultimately disbanded B-Specials, an organisation of supremacist Protestant army reservists. In a different universe he might have been on the other side of the encounter that night. Except that his devotion to music had liberated him...

However you looked at it, Brian McCoy seemed like an unlikely target. And yet he was the first to die, hit in the back and neck by nine rounds from a Luger automatic pistol as he tried to make his escape.

That was the mid-1970s. Two serving UDR ‘soldiers’, Thomas Crozier and James Roderick Shane McDowell, were found guilty of the murders and received life sentences. A third man, John James Somerville, a former UDA ’soldier’, was later also found guilty of the murders, However, none of the three gave details of who else was involved, or who had planned the attack. It has long been believed that there were elements of collusion, involving the RUC and the British Army.

A series of tit-for-tat killings were carried out by the IRA in response, possibly even including the murder of Eric Smyth, a brother in law of Brian McCoy, in 1994. That was the kind of country we had been living in: a nightmare, twilight zone, in which no level of brutality was deemed impermissible and families could have their own gunned down ruthlessly by either side or both.

CONFLICT RESOLUTION

The eruption of punk had lifted everyone, at least partially, out of the slough of despond into which the Miami massacre – a gruesome act of sickening butchery – had plunged us. As The Sex Pistols stormed the top of the UK charts in 1977, and The Clash became overtly political, all forms of authority were being questioned. For Belfast band Stiff Little Fingers, the Troubles became part of the subject matter – the band making it clear that they had no time whatsoever for the bores (their word) that were in charge.

Advertisement

It is no harm to remember the incendiary force of what the song, released as a single in October 1978, had to say.

“You got the Army on your street,” lead singer Jake Burns sang, “And the RUC dog of repression/ Is barking at your feet/ Is this the kind of place you wanna live?/ Is this where you wanna be?/ Is this the only life we’re gonna have?/ What we need is/ An alternative Ulster/ Alternative Ulster…”

We had been working loosely towards something like that ideal over the intervening 20 years, interviewing people from all sides of the political divide and putting them equally under the same kind of editorial pressure, to articulate what their vision for the future of that corner of Ireland might be. And if they were affiliated to any particular paramilitary group – the IRA, the UVF or any other tawdry outfit in between – we wanted to know exactly how they could ever hope to justify the viciousness, the brutality, the kneecappings, the murders, the summary (in)justices, the executions, and the outrageous bloody carnage of the bombing they had inflicted on entirely innocent people (as well as what they considered so called ‘legitimate targets’).

Our journalistic work had successfully drawn participants in the conflict out into the open. And it had given those who were genuinely committed to the idea of finding a peaceful solution something to work with. John Hume of the SDLP led the way. The Irish government and the Department of Foreign Affairs played every diplomatic channel. The Irish-American caucus upped the pressure. Bill Clinton saw that momentum was building.

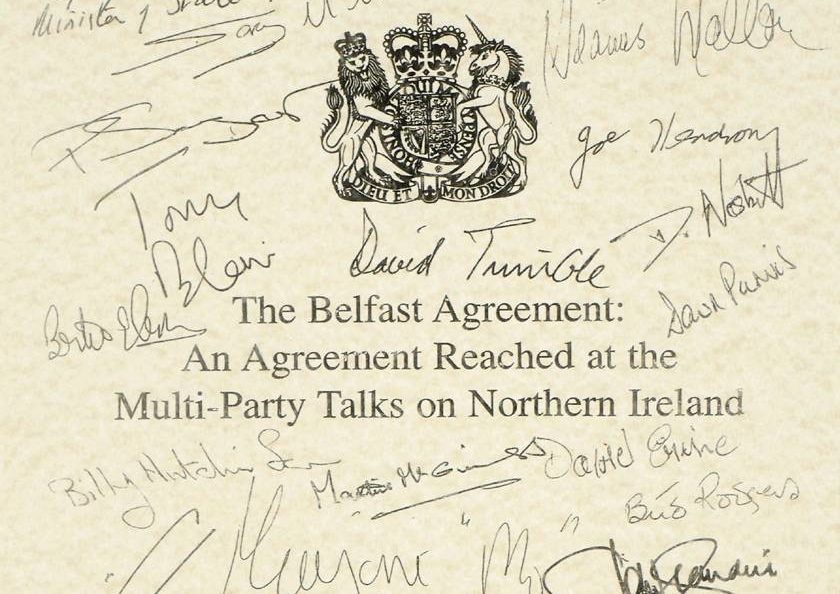

George Mitchell was appointed as a Special Envoy – and the painstaking work of conflict resolution ground into action. All-party talks started in 1996. Inch by inch, the process moved forward, through false dawns, and breakdowns. But the growing resentment among some Unionists notwithstanding, it was clear that the IRA leadership was on board and that they were prepared to commit to democracy through exclusively peaceful means, total disarmament, the renunciation of the use of force and an end to punishment beatings.

Loyalist paramilitaries would have to follow suit – and they did. It was game on.

And so it was that our worlds converged in Belfast that Easter. As the rock ’n’ roll clan gathered in the BBC, the troglodytes of the DUP were protesting outside the offices of the Ulster Unionist Party, accusing the leader David Trimble of betraying the union.

Advertisement

But there was no gainsaying it: they had been out-thought, outnumbered, and out-manoeuvred. The tide had turned. Barely aware that the deal had finally been struck, after the Awards show had been filmed, we partied through the night in the Europa Hotel and wakened up late to hear the good news.

A brave new world beckoned. The day of the bigots was done. Or was it?

whytes.ie

whytes.ieTHE INNOCENT VICTIMS

Looking back over what I had to say at the time, it is clear that my assumptions about the likely impact of what had happened that day in Belfast were wrong. But that is true of almost everyone. No one foresaw that the centre parties who had worked hardest to bring about the deal would be sidelined so soon. No one forecast that politics, and the Northern electorate, would treat John Hume and David Trimble – and the rest of the foot-soldiers in the SDLP and the Ulster Unionist Party – so badly. No one imagined that the extremists would begin to dominate – and that we would see Dr. Ian Paisley and Martin McGuinness become First Minister and Deputy First Minister of the Government of Northern Ireland.

For many the rise of the duo – who became known as The Chuckle Brothers – was an especially bitter pill to swallow. But that it was far preferable to the alternative – the continuation of political and sectarian violence ad nauseam – was indisputable.

Advertisement

So much has changed over the 25 years since the deal was signed. The Unionist stranglehold is over. The idea of a Protestant state for a Protestant people is dead. Sinn Féin is in the ascendant – in the North and in the South too. But there is more to it than that: a far higher number than ever identify as atheist or have otherwise left the baggage of religious dogma and tribal affiliation behind. Young people are more open and progressive. But we can afford to take nothing for granted. The poison injected into the body politic by Brexit has already created a more dangerous dynamic, with the DUP demonstrating once again that they are nothing more than self-centred enemies of peaceful co-existence.

And in a world where Russian spies covertly link up with dissidents of every shade and stripe, and likely provide funds and cyber support to the attempts being made separately by right-wing Nationalists and likewise Loyalists, to stir up old ghosts, and create havoc where and whenever it is possible, the danger of slipping back into the bloody muck and vile slime of brute sectarianism, hostility and violence is real.

Twenty-five years on, it is also more apparent than ever that the Belfast Agreement carried within it the seeds of its own destruction. In many respects, it reinforced the long-nurtured, grudge-held divisions, rather than shaping a truly sustainable, egalitarian, political future.

By now it is obvious that changes are needed, for a start to remove the veto that the DUP are currently exercising so destructively. But that way too, a different kind of perdition may lie. The situation demands – as did negotiations in 1998 – cool heads and stout hearts.

A way forward can be found. To get there, perhaps we need to think again of The Miami Showband – and of all the other innocent victims of the senseless violence that saw over 3,500 people killed and countless more maimed, injured and traumatised – and to decide this much collectively: as sentient human beings, we will never countenance a return to that grisly hell-on-earth.

Then the hard work will begin.

Read The Hog's reflections on the 25th anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement in the new issue of Hot Press: