- Opinion

- 12 Jul 20

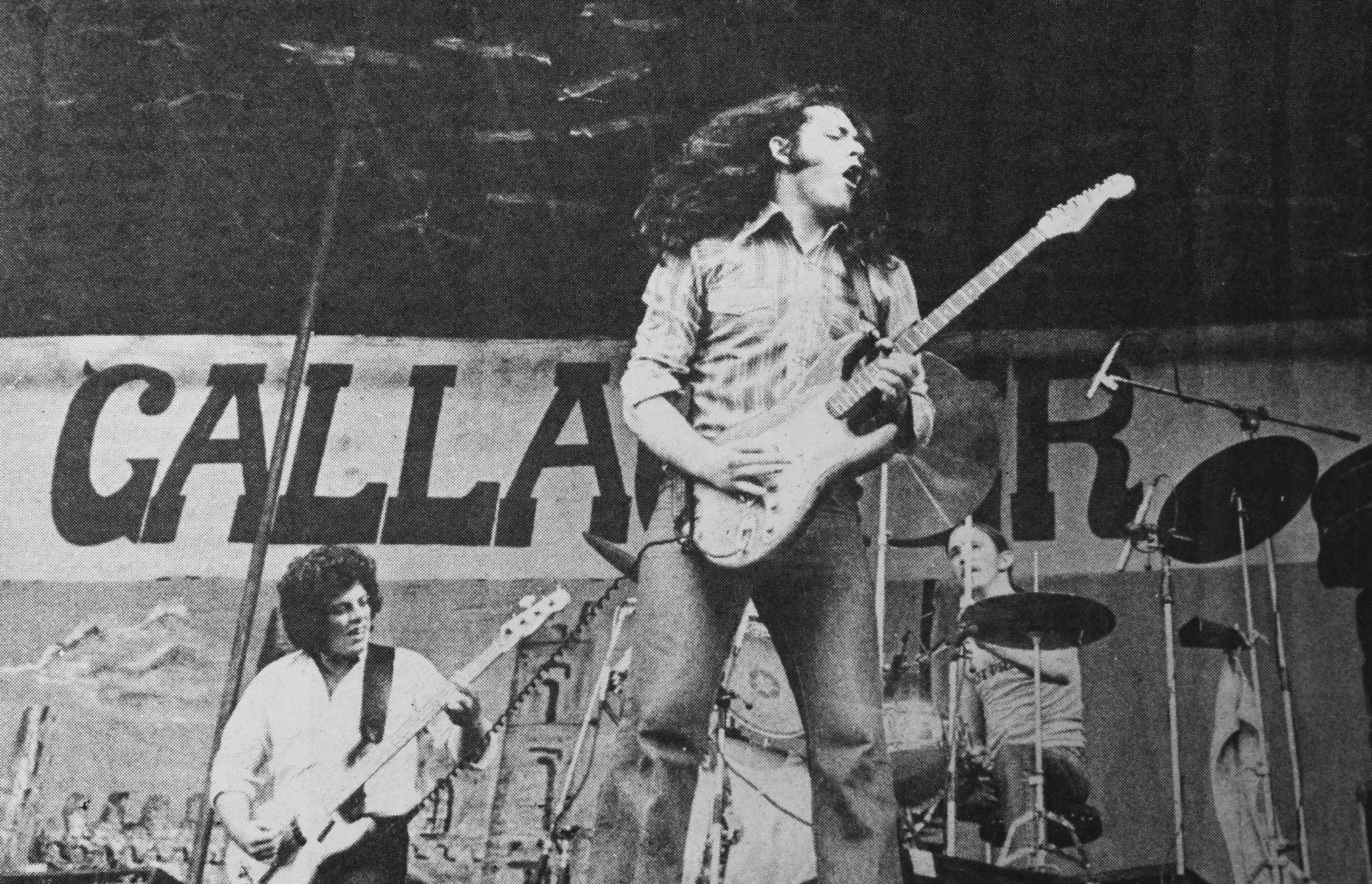

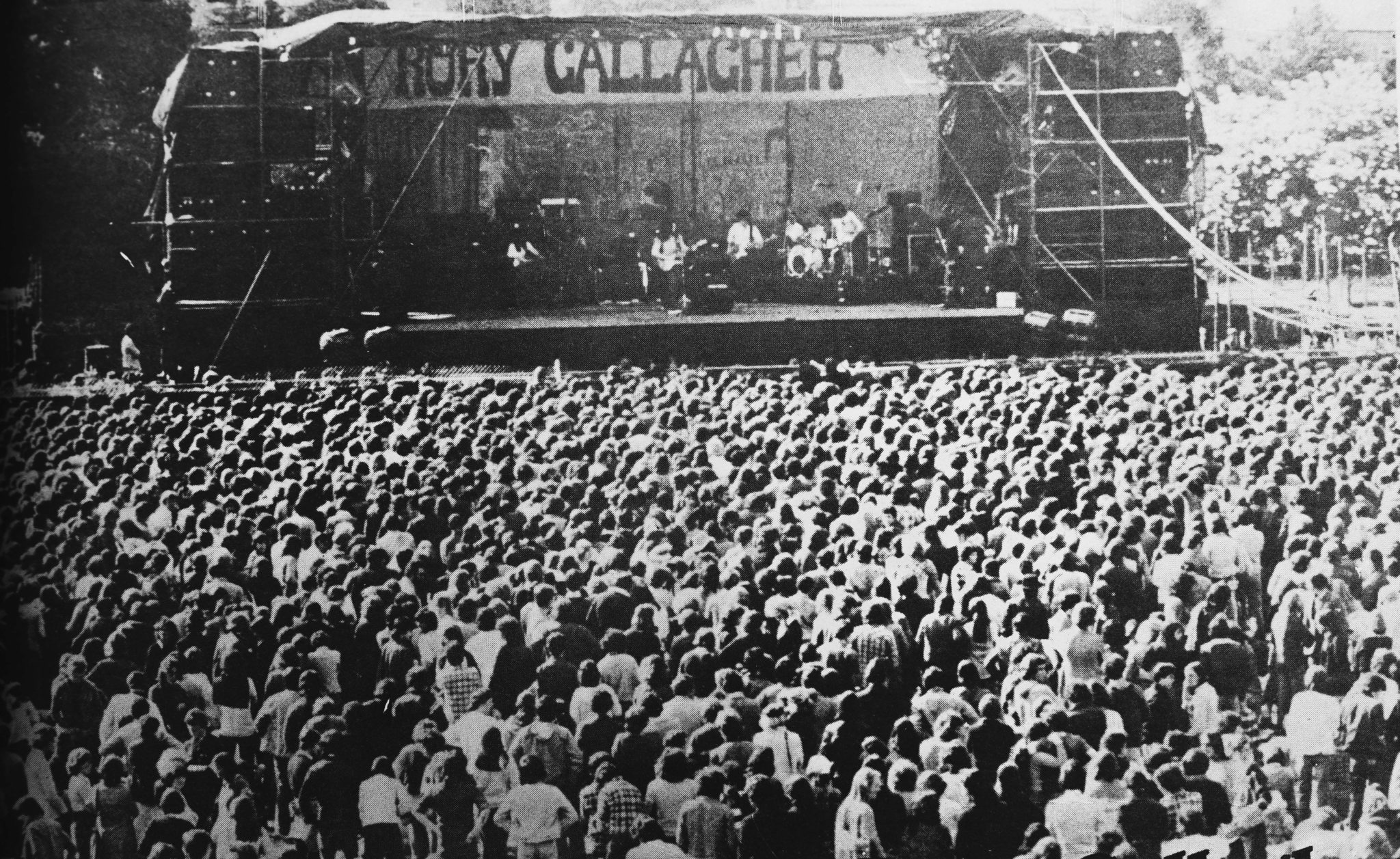

When Rory Gallagher hit the Macroom stage in 1978, it was against a fascinating if turbulent backdrop. Here’s his pre-festival interview in full...

It has been an exciting if often bruising period in music, with punk rock challenging the established order in a big way. Not that it was a period without its achievements for Rory Gallagher. Heading off the Rockpalaast Eurovision gig was one highlight, which saw him going out on the box before 28 million viewers across the continent – undoubtedly one of the contributing factors in his continuing rise throughout Europe. It was a shrewd move opening that particular show too, as anyone who misconstruced it in thinking he was ‘bottom of the bill’ will have failed to realise. By four o’clock in the morning, with Roger McGuire and Thunderbyrd on, the home-audience had dwindled to about one million. Understandably, some people prefer bed at that time of the morning.

More recently, there was his sell-out return tour of Britain, an achievement which underlined his continuing credibility there in spite of the changes in attitude precipitated by the whole New Wave buzz. Gallagher has always stood aloof from trends, charting out his own idiosyncratic course, through all the changes, building a reputation that’s based on a fundamental unwillingness to compromise his pervasive musical integrity.

But his profile was lower generally, for a couple of reasons. Initially he moved base to the continent from where he launched on a series of festival gigs and later into another area where he’s currently building well, Japan. But that move automatically meant less media attention in Britain, particularly with the music papers there concentrating so heavily on New Wave.

The element of bad luck didn’t help either. Rory went to Toronto to record his follow-up to Calling Card with Eliot Mazer, renowned for his work with Neil Young, handling the production. But in the middle of the sessions Rory broke his thumb by slamming a taxi door on it. That moment must have represented the ultimate musician’s horror, like some malignant fate has come to roost.

Rory recalls the incident: “I was just going back to the hotel one night. I got out of the taxi. It was about six o’clock – I was stone cold sober, I swear, and I paid the taxi driver and closed the back door. I must have been grabbing the frame of the taxi – why I should be doing that I don’t know – and the thumb stayed in there. Luckily the cab didn’t drive away. I looked for a minute – then I had to open the door and get it out again.

Advertisement

“So much for the Edgar Allen Poe bit, but there was a split second when I thought it was gone. Anyway I couldn’t do anything with it for five or six weeks, it was in a splint. I can’t even bend it yet. I can play with it but it just won’t bend. But I imagine over the months it’ll loosen.”

On the evidence of the recent London gig which I caught, it hasn’t adversely affected his playing at all but it can’t but have been a chastening experience.

“It makes you appreciate your hands more. You only have two of them! It’s funny how things run through your mind. For the first week I wasn’t sure what the story would be. You start getting all these Django Rheinhardt complexes. But it was irritating from the point of view of trying to make serious decisions on the album and on doing the tour. But we got over it, you know.”

But there was a major surprise in store at the end of the tour when Rory split his band line-up of seven years standing, dropping drummer Rod d’Ath and keyboards person Lou Martin and retaining bass player Gerry McEvoy. What was behind that decision?

“When you spend so long playing with the same people, you get inquisitive – you feel the need for a new beat and fresh personalities around you. There’s no technical reason. I just felt like a change. When you stop looking forward to playing with a particular line-up, you know deep inside that you should change. It was a good time to change, before it became a bore for everyone.”

Rory’s still uncertain as to what form the new band will take, though there’s the obvious priority of getting the long-delayed album finished. In fact he’ll probably scrap most of the work done with Mazer in Toronto and start afresh with a basic three-piece. At the moment, it seems certain that Les Binks will feature in the new line-up, taking on the job full-time after he completes his commitments with his current band, Judas Priest.

“The immediate thing is that I just want to get back to the bare brass knuckles of the sound. I’m going back to a three-piece for a while and if that sounds good, I’ll stay with it. There’s so much that I do guitar-style wise that can stand up in a three-piece because I play a cross between lead and rhythm and because of the acoustic knowledge I have. So far at rehearsals it’s sounded great with just three, so I’ll probably start the album on that basis and then just overdub myself on rhythm – or someone else.

Advertisement

“That’s more my thinking – getting away from the multi-layered sound. Going down to the bare bones. I’ve scrapped a lot of the songs – kept a couple of the ultra-hot ones – and added a few new ones.”

The ultimate question is whether one benefits enough from the added space afforded by the sparser set-up to compensate for the loss of an extra instrument to lean on and play off when desirable. Rory openly admits to being uncertain about the answer and indeed about the final outcome of his search for a sound that more satisfactorily represents his vision at this stage of his musical evolution.

Finally of the change he comments: “I guess it was probably just instinct.” With Rory Gallagher, that’s as good an inspiration to follow up as any other – indeed, it’s probably the best. Ireland’s guitar hero is above all else an instinctive musician; a natural born player who relies purely on his ability as such to gain attention in an increasingly hype-dominated field. It’s a refreshingly unorthodox stance and one that may stand in his favour in the long run.

My own feeling is that the media have consistently failed to recognise Gallagher’s merits. He has a very Irish reticence which may well have caused the British press at least to underestimate not only the range of his musical knowledge and prowess, but his intelligence also. The irony is that most writers could learn a hell of a lot from sitting down with Gallagher and letting the conversation flow.

Inevitably it’s emerged that he’s a voracious listener who’s often capable as a result of throwing an extremely interesting light on current developments.

We begin by discussing the resurgence of British R’n’B courtesy of the Feelgoods and the Pirates. I’m wondering if that’s been influential in bringing about Rory’s change of attitude. I ask how he expects his new sound to compare with Calling Card, which was his mellowest album – though it had its scorchers.

Advertisement

“It’ll be different from Calling Card – it’ll be a rougher sound, though even that album had a lot of live lead guitars on it. I still try to on for that. As the albums went by I gave up the idea of singing live. On Tattoo and Blueprint they were literally live vocals – but it was really impractical. I used to go for an ethnic blues approach whereas I wasn’t really doing ethnic blues material, so that was a bit off-centre.”

But whatever about returning to a more basic R’n’B sound, there’s no way he’s about to abandon his song-writing muse. It’s a department in which his ability obviously outstrips that of the bands who’ve emerged during the past couple of years.

“You can always do a couple of old R’n’B numbers and the album will work as that but when you’re trying to write songs and to marry the two things together – your own feeling for R’n’B and blues and rock – that’s where you sink or swim. You might get away with just doing old R’n’B numbers nowadays – everyone would say it’s neo-R’n’B and so on, but that wouldn’t satisfy me.

“If you can come up with new compositions that still have the blood’n’guts of R’n’B, that’s really what I’m aiming at. I feel my new material is good enough to stand up as songs on paper, but there’s plenty of room for meaty playing.”

In other words, Gallagher has long surmounted a crisis that still afflicts the likes of The Pirates, Feelgood and Wilko. On the question of using keyboards, he ruminates.

“Elvis Costello’s This Year’s Model – the keyboards are great but that’s a very peculiar style - that’s almost like a 1960’s Dave Clarke Five-type organ sound. The Vox organs and the Farfisas are back. Soon showbands will be made again,” he laughs. “There’s so many weird bits that creep in to Costello’s music. You can hear Tommy James and the Shondels, Del Shannon and lots of other non-hip things. I’m sure he’s a renegade from a London showband. I’m sure I saw him years ago in a showband. He even uses a Fender Jazzmaster which was the showband guitar. Not that I’d hold that against him, but it’d be a scream to find out he was a member of one of the early showbands.

“The jazz-master was a really out-of-style guitar – because the pick-ups on a jazz-master are actually steel guitar pick-ups, they’re ultra-clean. They were mainly used for Ventures kind of music, so you can’t really distort them no matter how much you turn them up - but they respond to pedals very well, so the fuzz tone works well on them – they’re not very high output.

Advertisement

“I saw them in London going for £90 in the shops – no one could sell them ‘cos you couldn’t get the blues sound out of them. The funny thing is that you notice all these other groups using them now – the guy from Television has one, I think Jonathan Richman has one. They must be the guitars to get! Everyone will be selling their Strats and Les Pauls. That’s great – I love to see old guitars show up again. Burns will make a comeback next and Hofner. I saw a couple of queries about Hofner in International Musical. That’ll be the next thing.”

It’s clear that he’s well aware of what’s currently going down, and laughs at the thought of Steve Jones of the Pistols going through the guitars – a Gibson Black Beauty, white Gibson Les Paul Anniversary and a Gibson Firebird respectively, on the group’s Amsterdam gig, the last in Europe, which Gallagher caught.

He comments: “I catch up on things in my own time. Between trips to the States and things, you pick up an odd album, like the Ramones, and the New York Dolls when they happen here. Costello’s the most important of the new lot but he’s so conventional really when you take away the press image. He could be an American neo-bubblegum band (laughs).

“While I like to keep up with what’s new, I don’t like to discard good things from the past. Having listened to so many records, you spot little things that subconsciously must influence them, whether it’s something like The Ventures... it almost seems to be the trick at present, to absorb influences of this that aren’t hip to like – like Tommy James and the Shondels. Tommy James is not on – but if it’s squeezed in under Costello’s name, it’s alright. Maybe that’s because it’s second time around and the lyrics are crazier...

“What Costello is doing is writing all these spiteful songs, which is great, but he’s moved away from the blues and rock background.”

Gallagher also regards Graham Parker and the Rumour highly – but closest to his heart among recent developments is undoubtedly the revival of the blues in the hands of Muddy Waters and Johnny Winter in the States.

“This time they’re modernising the blues not by adding synthesising tricks and things. They’re just doing it like it was, except sharper and slicker and prouder. They’re not trying to hide it like on ‘Electric Mud’, behind a load of wah-wah and things. You can hear it in Muddy’s voice too – he’s not inhibited. They just went ahead and had a damn good blow.”

Advertisement

And be fucked to all the fashion, an attitude much like Gallagher’s own. There was a time when things weren’t so clear in Johnny Winter’s head.

“Yeah. He was inclined to jump on various glitter bandwagons. He never completely lost it but he was getting pretty low. This was the last obvious step for him to take, so he could get back to the blues and groove out of that. I’d be keen to see him move on again, but not in the same way he did before.”

One of the real joys of Waters’ transformation is that he no longer feels the need to tear off on those crazed ten-minute solos that cover a vast expanse of ground and yet end up going from nowhere to nowhere, which afflicted his later playing. Rory might make things a bit more compact too.

“But I wouldn’t revert straight away and start doing six songs a side. I always like room to kick around on the guitar. The thing is that there’s only twenty minutes decent cutting time per side. I like room to roam around and play the guitar, even though it’s not hip to play guitar anymore. I write songs to enjoy singing them, to get the lyrics across and to have a good belt on the guitar.

“With a different line-up I might get away with shorter songs without them sounding shorter. I’m only wondering what the guys who’re putting on six songs a side are going to do next year. They’re bound to want a stretch out musically, or maybe they’re happy enough within the confines of what they’re doing.”

Gallagher’s obvious love for the most divergent strands of rock in all its related musical forms poses the question of how he sees himself. Where does he stand between the different idioms?

“That’s a good question really, ‘cos I’m always caught in vacuums and generally misunderstood press-wise. I don’t want to be categorised – but not in the usual sense in which that’s said. But I’m not really a rock’n’roll artist, even though I’m crazy about Eddie Cochrane and Gene Vincent. I’m not really a blues reviver in the sense that John Hammond is or Stefan Grossman is, even though I’m very fond of the old blues and country blues. I incorporate a bit of rock’n’roll, R’n’B, a bit of blues and a bit of folk into my playing – and quite often with the market if you’re not prepared to streamline yourself into a fairly recognisable bag, it’s very difficult to sell those extra albums or for the press to pick up on you.”

Advertisement

There was a country flavour on Calling Card, indicating another sphere of interest for Rory – Waylon Jennings being a favourite.

“I like all these kinds of music. But blues-based is still the best description for what I’m doing. In the end though, the songs I write usually dictate where I’m at.”

One area we haven’t touched on at all is jazz-rock. Whereas Rory feels a certain admiration for the likes of Jeff Beck and Al di Meola, he’s got his reservations about the whole development.

“When it comes to jazz, I’m a saxophone fan. Trumpets too. I’m not a great jazz guitar fan, even though I like some players. I’m fonder of ‘50s jazz – Don Cherry, Pharaoh Sanders and the Coltrane era. The new stuff can be interesting enough but the manic element is smoothed out to an electric cool.”

Yeah, it misses a gut feeling. Rory has one final comment on the subject that maybe says it all: “Simplicity in music can be much more effective than technical escapism.”

For Gallagher himself, it must be perturbing that he hasn’t had a new album for nearly two years. He doesn’t make any bones about it.

Advertisement

“It’s frustrating because some things have had to go into the locker forever. It’s nice to have an album every year. If you don’t have an album for two years, people assume you’re having a dry-out or that you have to do something radical about your playing – or that you’re on safari or something! But it can be hard when you’re working and touring constantly. I’d hate people to think I’d dried up for songs – the opposite is the case. Sometimes a gap isn’t bad – it gives the old albums time to settle down and the compilations time to get out of the way. What happened on Calling Card was that a compilation album and a pirate album came out at the same time and shops in New York had all three, in equally striking sleeves. That really caused problems. But I wouldn’t like to have a gap of two years every time. If this next one goes according to schedule, I’ll try and follow it up fast, six months later or something.”

In all probability, the whole issue won’t worry Gallagher’s following unduly. Most of them know his attitude too well to misconstrue the situation – and anyway they’re a particularly loyal bunch. They go for his no-bullshit anti-star style. He’s human-size even if he can be brilliant. He’s also a worker like the majority of them. Gallagher has built up his audience through the hard grind that constant touring involves, through working the grass roots and giving real value for money, rather than via promotional hype and image-projection. The result is that often the scale of his success can be underestimated, especially in the States.

“We’ve a bigger following in America than would meet the eye. And that’s not just a line. We haven’t been there for a while because of the various delays and trying to catch up on commitments in Europe and Japan. Europe is definitely the stronghold – but you get the impression from the lack of what you’d read about the States that there’s nothing happening there. We’ve done twelve tours – even if it were on a humble basis, that wouldn’t be a bad achievement – and we’ve done a lot of important gigs, played a lot of great gigs... but then there’s so many little limitations that I put up against myself that slow up the success process in the States. I suppose somebody should kick me.

“I’m not hung up that we’re not in Madison Square Gardens. I’m just keen on getting that elusive top ten album and retaining the audience we have in the colleges and clubs and some of the civil halls. Some days you get frustrated and think, ‘This is ridiculous, we should be so and so’, and other days you see the compromises that musicians have to make to get to that high level and think, ‘I wouldn’t do that’.”

So what sort of limitation is he talking about?

“It’s quite hard to sell me over there image-wise and I do just as much promotional work as I think reasonable. Basically, one could crack through on a Bob Seger level, which I think is fairly respectable. He’s still playing what he likes, it’s just that people caught up with him eventually – that approach appeals to me more than becoming last year’s model! But the music business in America is weird. You find people in the top ten there and they can’t fill the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles or something – we wouldn’t have the top ten hit, but we’ve outsold people who have, in concerts.

“My ambitions are still high but the Shea Stadium isn’t on my list. If it happens, fine, but I always specify to the agents when we go over, to keep in some club and college dates so we wouldn’t end up in that second or third on the bill, big rock’n’roll stadium-touring routine, that you can end up on.

Advertisement

“I’m not as pliable as a lot of artists. I wouldn’t do something if I think it’s going to haunt me for the next couple of weeks, some old publicity stunt or something. But we were stuck on a very weak label in America for years unfortunately, which didn’t match the popularity we’d achieved. Everyone knows it was Polydor. Unfortunately, the Polydor years were the years we were really hammer and tongs touring in the States. Since the Chrysalis days, the gaps between the albums have been longer and there’s been more of an emphasis on Europe – but I don’t think we’ve lost ground. You have to be a little bit philosophical and patient in the Chinese way.”

One thing which has certainly worked against him is his consistent refusal to release singles – a policy which underlines the extent to which Gallagher remains his own man, refusing to be pushed into the standard packaging process of the business. However, it’s not something which he sees in solely black and white terms.

“I go through phases of saying, ‘Take the song off the album and bring it out. What the hell?’ But if anyone says to me ‘Edit that single’ or ‘Fade it out’ then down go the shutters, so as often as not, the album’s been out and gone before I make up my mind. But then I get excited when I see a good single going up the charts – I think it’s great. I’m probably a bit naive about it. Any other person would probably bring out a single from the album, if it takes off great. That should really be the only standard. It’s just that I got a bad feeling about it at one point – I saw a lot of good bands and artists who were playing their own music, trimming it down to the old two minutes and next thing they’d be on Top of the Pops and Junior Choice and so on – though the New Wave thing has brought a little hope into the singles charts.”

The frustrating thing is that radio the world over is so singles-oriented. By not releasing 45s, Gallagher has effectively denied himself access to 90% of radio air-time throughout the last decade. And, as he puts it himself: “How many times can you end up on the Nickey Horne show or John Peel - or Alan Freeman might play my record?”

Clearly an awareness of the music business’ capacity for dragging musicians of talent down to the level of puppets has given rise to a kind of puritanism that may well have some justification, but is ultimately impractical – and basically pointless when someone of Gallagher’s integrity is involved in the first place.

“Maybe I’m just too cynical about the whole system. Maybe with the new album I’ll have a bash and see what happens. You can get so hung up on ethics and idealism to the point where it outweighs the whole issue anyway.

Advertisement

“I don’t set out to be a pill about the whole music business. I just try to do my own thing – the old cliché – and it turns out like I’m at odds with a lot of what goes on. I don’t have any crucifixion complex about it. I have a big following. I can do what I want on the albums. I can play what I want at the shows... it could be that I’m a folk-type person in a rock world. The other side of it is too time-consuming.”

A folk type person in a rock world - that could offer the perfect analysis of the root of the tension. With Gallagher, the music is everything. He plays rather than acts. Nor is he in the slightest bit concerned with projecting an image, which has become such an integral part of rock, for better or worse, in the ‘70s – whereas those concerns are central to, say, The Boomtown Rats.

“I saw them miming on Top Of The Pops and heard some of the album. They’re a good bouncy band. They’re full of beans and so on. But they seem to me to be too conscious of the media, too conscious of publicity. They’re clever at it. You have to salute Geldof for being the best PR man around. But in time – it’s probably the square thing to say – you have to make music a bit more memorable. It’s one thing to have supercharged energy but you have to balance it out with a bit of substance.

“But they’re getting into the top ten, so from their side of Ludo, things are working fine. They did kick up a bit of a storm and liven up the scene, which is great, and it’s another Irish act which has made it in a pretty big way, which is also great...”

But their’s is certainly not Rory Gallagher’s way - and however many kudos the Rats have garnered, you can’t but advance the former’s maverick independence. There’s one way that he knows he can make contact with the fans and that’s on the road, so that’s how he’ll do it. It’s his life.

“I love it. I’m addicted to it. But it does get to you eventually, in the sense that you can’t do without it. It becomes harder to function off the road, which has always been the case with me. I’m really looking forward to getting back in there with the new line-up and new songs.”

I don’t think there could be a more appropriate ending for a Rory Gallagher interview. But what strikes me at the end of our conversation is this – that Rory Gallagher will always be a musician. Obvious maybe – but important. In that sense, he’s the real thing – dedicated, committed and one of the finest guitarists around to boot. And whatever else gives, he and Bob Seger and Dave Edmunds – you can name a few others I’m sure – represent the past, the present and the future of rock’n’roll.

Advertisement

New waves come and go – and I can see plenty who’ve gained prominence in the most recent schemozzle becoming film stars, PR men, journalists and even poets in a few years time.

But there are human-size stars around for whom music is life, who get on with their playing and give satisfaction wherever they gig. They’re the ones who’ll endure, irrespective, and Rory Gallagher is one of them.

Never underestimate an old warhorse.

The special Rory Gallagher 25th Anniversary Issue of Hot Press is out now – featuring reflections on Rory's legacy from President Michael D. Higgins, Imelda May, Johnny Marr, Mumford & Sons, Mick Fleetwood, Steve Van Zandt, Slash and many more. Pick up your copy in shops now, or order online below:

![Minister James Lawless: "How do we have two different rules [for alcohol and marijuana]?" Minister James Lawless: "How do we have two different rules [for alcohol and marijuana]?"](https://img.resized.co/hotpress/eyJkYXRhIjoie1widXJsXCI6XCJodHRwczpcXFwvXFxcL21lZGlhLmhvdHByZXNzLmNvbVxcXC91cGxvYWRzXFxcLzIwMjVcXFwvMDRcXFwvMDMxNzA1NTZcXFwvTWluaXN0ZXItRURVLWJ5LUFSLTI2LmpwZ1wiLFwid2lkdGhcIjpcIjMwOVwiLFwiaGVpZ2h0XCI6XCIyMTBcIixcImRlZmF1bHRcIjpcImh0dHBzOlxcXC9cXFwvd3d3LmhvdHByZXNzLmNvbVxcXC9pXFxcL25vLWltYWdlLnBuZz92PTlcIixcIm9wdGlvbnNcIjp7XCJvdXRwdXRcIjpcImF2aWZcIixcInF1YWxpdHlcIjpcIjU1XCJ9fSIsImhhc2giOiI5Nzg2MDBhOGZkZTdmZjcwMGM3ZDE5MDdkZjhlYmE1MmQ3YjAzZjMwIn0=/minister-edu-by-ar-26.jpg)