- Opinion

- 27 Aug 20

Susannah Dickey On Tennis Lessons, Female Friendship and Writing Trauma

“In writing trauma, I felt the most evocative way of doing it was to take a reader and force them to either be complicit in what was happening or to have to consistently actively reject their friends and the narrative."

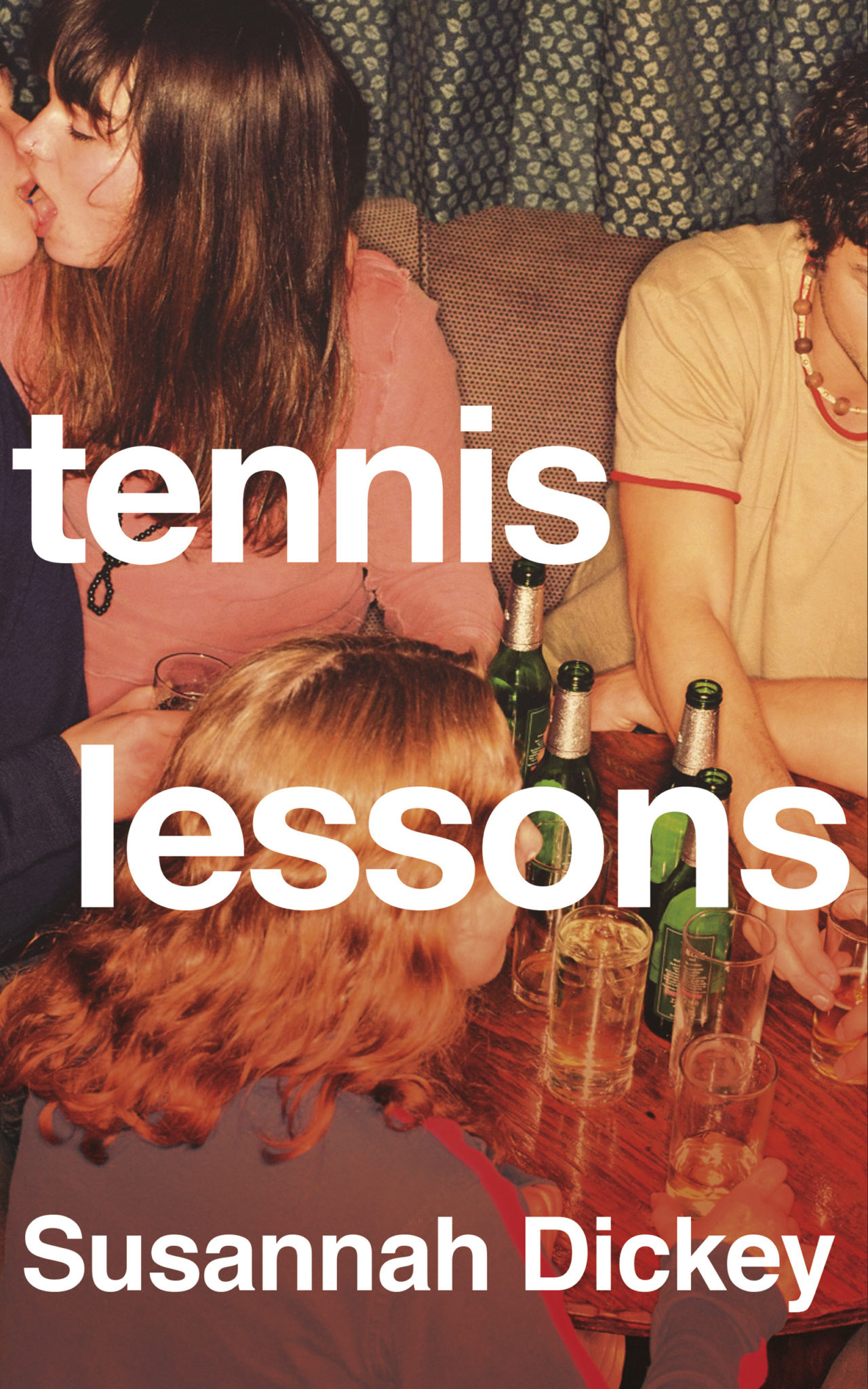

“I write poetry because I love language, and I write prose because I hate myself,” says Susannah Dickey, the author of Tennis Lessons, an offbeat coming-of-age novel released in July from Doubleday.

The Derry native is finishing her answer to my question about the relationship between her poems, which won the inaugural Verve Poetry Festival competition, and her debut novel, which has the vividness of verse. It’s just like Dickey to end her response on a startling admission: Tennis Lessons brings almost every paragraph to such a moment of dark and hilarious clarity.

Tennis Lessons follows a Northern Irish woman from ages 3 to 28, capturing in both gross and lovely vignettes her struggles with her body, sexuality and social position. Dickey knows that watching her main character limp from childhood to mediocrity is far from uplifting: “I wonder why this idea of growth, improvement, change in a character should be an aesthetic principle when so few of us are growing or improving,” she says. “Like, I'm someone who is very familiar with stagnation, so I thought, you know, why not write that?”

The main character of Tennis Lessons remains unnamed, addressed by the narrator as “you.” This second-person narration inserts the reader into the story, forcing us to imagine exactly what it’s like to be a young woman who abuses alcohol, suffers sexual violence and watches her parents quietly drift apart. By the end of the novel, readers find themselves looking at their own bodies in the protagonist’s self-loathing way.

Dickey meant this reading experience to be challenging: “In writing trauma,” she tells Hot Press, “I felt the most evocative way of doing it was to take a reader and force them to either be complicit in what was happening or to have to consistently actively reject their friends and the narrative.” “Complicit” is a good word, here — because another strength of Dickey’s second person is that it makes readers experience their interconnectedness to others, the way even their smallest gestures can hurt a person such as Dickey’s lead.

Dickey can be self-deprecating, and she undersells the importance of this project. Think of recent popular coming-of-age novels — Looking for Alaska, Middlesex, The Kite Runner; all are bildungsromane, meaning they chart the kind of growth and change Dickey rejects. A better reference for Tennis Lessons might be The Catcher in the Rye. But unlike JD Salinger’s iconic rendering of teenage angst, Dickey’s novel is not oppressively male, heteronormative, or even pessimistic.

Tennis Lessons is dark, but it lets light through its cracks; that light just doesn’t come from the college-to-career pipeline or heterosexual romance.“It’s not a book that is perceived as a fun book,” Dickey says, “which is a bit sad for me because I think there is joy to be found in it.” She elaborates: “It never felt to me like a book that would prioritise heteronormative romantic relationships,” she says. Instead, for her, “a close friendship is a safe place where there's often a tireless amount of patience, and there's unconditional love there.”

The heart of Tennis Lessons is the dynamic of care between two women: the main character and her best friend, Racheal. Dickey finds something political in their intimacy, which exists outside of the normative relationships and life paths her protagonist despises. “Their friendship felt really important to me in showcasing the quotidian concerns of young Irish women,” Dickey says. “It might not be a novel that’s viewed as explicitly political, but I think the concerns that manifest through the politics at play come through in their friendship.”

So what’s next for Susannah Dickey? She’s finished another novel, split between two female protagonists who live in the same apartment building and are locked in a “non-intuitive plot of revenge that involves cutting fingernails and the other woman's shoes.” She’s also exploring “media perception and media portrayal of dead women” by writing poems about the Isdal Woman, whose burnt body was found in Norway in 1970 and who may have been a Cold War spy.

Whatever Dickey puts out next, we have a lot to look forward to — more of her startling perceptiveness and a “bizarre interaction involving a pregnant woman, a fur coat and an ATM” that she cut from Tennis Lessons. “I think I’m going to try to shoehorn that into something else,” she says with a wry laugh.

Tennis Lessons is out now.