- Opinion

- 29 Dec 20

As part of the The 12 Interviews of Xmas, we're looking back at some of our classic interviews of 2020. Long-fancied and admired, David Keenan surpassed all expectation with his quite brilliant debut album, A Beginner’s Guide To Bravery. Back in January, Pat Carty caught up with an artist on the cusp. Photos: Miguel Ruiz.

It’s a couple of years since I first heard of David Keenan, his management having to practically break my arm to see him do a support show in which I had little interest. I was wrong – of course - and that unique voice which seems to meld the swoop of Buckleys Tim and Jeff with elements of sean nós that you remember even if you don’t remember, the rolled up sleeves and the braces that also hark back to a different time, and, most importantly of all, his songs, won me over. I heard early versions of both ‘Good Old Days’ and ‘Tin Pan Alley’ that would have made even the staunchest opponent of the sensitive-types-with-acoustic-guitars contagion that had swept through Irish music take notice. Here was an artist who seemed very close to fully formed, although we would have to wait a while for the opening chapter to arrive in the shape of an album.

In reality, the story started long before that, in his grandparents’ house in Dundalk to be precise.

“There were subtleties, I think purposely, left around," Keenan says in that soft burr, over his cup of tea in the Library Bar. “My uncle left his guitar in view on top of the wardrobe when I was a kid, and he’d half-heartedly say ‘don’t touch that!’. My grandparents’ spare bedroom, there was always gems in there. Voltaire, Dostoevsky, Flann O’Brien, all the things you’re told you should read, they were all there. You’re stumbling with these sparing partners, picking things up, ‘What is this language?’ I tried to infiltrate it.”

We’ve had this discussion before, so I know where he’s coming from, but Voltaire and Dostoevsky just laying around is unusual.

“It is odd, it was my grandmother, she would never boast about any of that, but it was present and available. That was a council estate in the heart of Dundalk, it’s not as if I came from a certain standing, except the one that I knew and that I’m proud of. Art and literature are accessible to all of us, it’s just a fucking spell concocted by the powers that be to make you feel that they’re not. It’s the generosity of all these masters, these men and women who leave these things behind for us to find, these bread crumbs.”

Advertisement

Road maps?

“Road maps to the soul,” he agrees.

There was music too, a lot of country played in the house. “I’ve a great respect for American country music, it condenses a lot of intricate emotions into three-chord songs,” David acknowledges, although the Irish version gets short shrift. “My father would try to indoctrinate me into Irish country music but even back then I found something very suspicious about a Leitrim man singing in a Texas accent.”

It was music of a slightly more authentic stripe that got him going. “Hearing Leonard Cohen’s voice for the first time, I was entranced by that, and ‘The Mercy Seat’ by Nick Cave as well. I remember listening to that at twelve years old and thinking that’s not Nick Cave, that’s a fella on death row. It put the chills up me and I think I found in that moment that you could create and invent your own world.” When pushed about the exact nature of his attraction to Cohen and Cave’s work, Keenan reckons it’s the fact that “it’s lived in, there’s an honesty there, a celebration of all aspects of the psyche.”

Into The Music

We’re not quite there yet. At seventeen, having completed a computer course, Keenan stood at the threshold to a certain kind of life. He took one look and ran. To Liverpool.

“I was looking for escape and adventure and some flag to fly under,” he remembers now. “Liverpool seemed like this Mecca. I felt I could be somebody there, live off my wits on the streets.”

Advertisement

If that doesn’t sound completely planned out, that’s because it wasn’t.

“The God’s honest truth, coming in on the boat to Birkenhead, it dawned on me, where the fuck was I going to stay? I was so green, I got on Google maps, found the cheapest hotel, and stayed there for two nights.”

Two similar yet different sets of musicians had attracted him. Hearing the Libertines’ second album at fourteen from “a Protestant, on a bus, who spoke in an English accent, wearing a pair of leather fucking cowboy boots! They were a gang, it was their whole thing while everyone else was listening to Lady Ga Ga or some shit which just didn’t translate”, and that great lost loon/mystic of Merseyside, Lee Mavers and his band The La’s. Keenan’s eyes light up when he talks of them. “I’m thinking of the BBC sessions, it’s acoustic and rootsy. It’s the sheer brilliance of the musicianship, the harmony and that skiffle Mersey beat. In terms of melody, Mavers is one of the greats. People talk about Brian Wilson, but I think Mavers is right up there.”

God takes care of artists and fools. “The second night in Liverpool I found Barry Sutton (former La’s guitarist) in a café. I’d read somewhere he’d done a gig with Jinx Lennon, so I had an in with him. I was mesmerised, he played like Bert Jansch, he never stopped talking, and he was as mad as a brush. They all seemed like that there, every kid was the best musician you’ve ever heard, they all looked great, beautiful girls, excitement, you know?”

It sounds like freedom, the diametrical opposite to the shirt-and-tie shackles the other world offered.

“That scared me,” David agrees. “I was afraid of the sadness that I saw in people like the course instructor, the boredom, anger, and frustration that was in everyone. I didn’t know what it was then, but I know now it’s about finding something that you love and holding on to it, because we’re all gonna die anyway!”

The odyssey to Liverpool, then, is the beginner’s guide to bravery, the bravery to see out a different kind of life, through music and art.

Advertisement

“Yes, it starts there,” nods Keenan. “I had never even thought about getting out of Dundalk. Music and art was the portal, it was something that I understood. When I started reading the Beat poets, something just clicked – it was the rhythm and their sense of freedom.”

Kerouac’s philosophy of living for kicks?

“Their sense of carelessness. People were so full of fear, coming from a small town. I was trying to break the chain and taking that step - going to Liverpool - that was it. When I came back, I knew I had a story in my arse pocket, I had lived it.”

Inarticulate Speech Of The Heart

David’s talent first came to people’s attention through a drunken back-of-a-taxi rendition of ‘El Paso’ that ended up on YouTube, a song he quickly outgrew, but his foot was now in the door. He moved to Dublin, attracted as much to the myths of the city as anything else. “You know yourself, in Dublin it’s easy to feel like you’re walking the same streets as all those people you’ve read.” His reputation grew with the release of songs like ‘The Friary’, ‘Lawrence of Arcadia’ and ‘Cobwebs’ – none of which would make the cut for the album – and high-profile support slots with the likes of Damien Dempsey, Glen Hansard, Hozier, and Hothouse Flowers.

Advertisement

“There was a sense of deep connection watching the Flowers, Liam Ó Maonlaí especially, surrendering to the music every night.” Keenan recalls, with obvious affection. “The improvisation is something I brought back to my own band: we need to drop our shoulders more. I never dance but I saw Liam moving and I started dancing.”

Momentum built – he headlined Whelan’s, he opened the Electric Picnic - but the album still didn’t arrive, Keenan waiting until the conditions were right to capture what he was after. He had dropped hints of a possible double album with different backdrops.

“I did it, I recorded it in three different environments, with The Organics (a sort of string quartet), on my own in the room, and with the band, but when I put them up against each other, it didn’t happen. I was kind of looking for this Orson Welles radio play, but it didn’t sit together on a record. I was ready to make an album a couple of years ago, but things didn’t align – I didn’t have the right band and I wasn’t mature enough to stand by what I was saying in these songs.”

Keenan agrees that the waiting has made for a stronger calling-card.

“I think the fat was trimmed off. The songs are condensed memories and it is a fucking live record. The temptation was there to rush it, but I was holding on to these burning notes. The songs are part of the experience of living life the last couple of years, I’m glad I gave it the time that it needed.”

As well as newer work like ‘The Healing’ – “that came in the post in August and demanded to be on the record”, songs as far back as ‘Love In A Snug’ and ‘Good Old Days – “they were there pre-moving to Dublin, those songs are four years old” - are also given space on the record. So much has happened over the last few years that surely there is now a little impatience with the older material?

“There is," David admits, “but I learned to be patient over the summer, to let go of the burning rope. You want this to be a strong body of work and the next record is already written, and the one after that. There’s always songs in the post and I realised ‘Hold on a second, I’m not going to cease to be at the end of recording this album.’ This is a starting point, this is chapter one.”

Advertisement

His Band And The Street Choir

The main recording for the album was done over five days in May of last year – with two additional days in August – under the eye and ear of producer/guitarist Gavin Glass in a studio near Dublin’s Hellfire Club.

“It was an intense, physical experience. Things had to align and it’s not just about who’s a great player, it’s about who you can fucking trust. I wanted to record in a certain way and it was just fucking time. We didn’t leave the studio.” There’s pride in his voice as he tells the story. “I think there’s three first takes on the record, and every other tune is three takes max. I don’t speak a musical language, but I can speak an emotional one. I use images as a reference and tell the lads what I’m seeing in my head.”

And that’s where the expertise of his crack band came in.

“It’s a subtle move on the piano from Gavin, it’s a melody from Gareth on the violin, that’s the exciting thing about collaborating with people in such an intimate way. This band can read my body language. I had references – chain smoke, colours, Degas, fluidity, movement. ‘Unholy Ghosts’ for me was a DMT release in the brain, I’d be screaming ‘more colour!’ at Gavin’s guitar playing.”

Like his heroes before him, Keenan’s lyrics are about world building, a romanticised Hibernia populated with bowsies, poets and lovers that we’re invited into. “I wanted the lyrics to be read and stand up on their own,” he says, “without the music.”

Advertisement

You dream of 'James Dean' working for Irish rail: are we talking about the beauty in ordinary toil?

“I love that, the beauty in ordinary toil. He’s confiding with me in the bar about his rejection of being an icon, he's harping for the holistic life, driving a train. Characters in my songs say things that I'm not brave enough to, and I get the satisfaction of being able to vent.”

Are you the “poor Samuel Beckett”?

“Beckett was stabbed by a pimp when he moved to Paris. I was reading this at the breakfast table and it said you fucking write this or somebody else is going to, so that was my opener.”

In 'Unholy Ghosts' it’s “the ones destined to get left behind interest me the most.” Is it a kind of a doomed romanticism that you revel in, those who refuse to fit it the way they are expected to?

“I think I revelled in that kind of romantic way of life, living in a coat covered with dog hair with a suspicious moustache, drinking wine every day, meeting street people who were incredible poets, people who don't get a look in in life and it's a kind of celebration of them.”

There’s a Donleavy-esque sense of careening through the city, life at a hundred miles an hour feel, but also a sense of wanting the preserve that part of the city that is being taken away.

Advertisement

“Yes, I think we're living in a time where it's the death of the character. If we were living in a different time, the street people would be revered.”

A few decades back, you and I would be in the Catacombs with a bag of stout?

“I think that's in our emotional DNA, our make-up,” David offers. “I think you and I are drawn to the same era and try to carry that. Do you know that great Anthony Cronin documentary where he has the three writers by the Liffey and he says that the middle-classes were on their tram home, contented to be sat by their fire with their whiskey, contented with Yeats and Synge but little did they know, genius as sharp toothed as ever was still swimming in these waters, and it's happening again, there's a rebirth.”

The man who gets even with God might be the artist, the only figure with God-like powers.

“I was gifted a book called The Man Who Got Even With God and when you're a young man with notions, to get that into your hand... But I've been on that search, if you look up in the stars, you see a divine order of some sort.”

I’ve never been completely convinced of that, a divine order in chaos, but I know the artist who creates his or her own world establishes their own holy order.

“Creativity is an expression of man's ability,” David says, countering my agnosticism. “It's the soul speaking and that's why I pursue it.”

Advertisement

When pushed on spirituality, Keenan pairs it with music.

“Music for me is a gateway to a higher state of being and a means to connect with more than one individual. It unifies, it’s an arena in which to express and heal, and to feel connected, to feel part of something. Atheism for me is a dead end, I’m a storyteller and that’s no good to me. You observe nature and you think ‘wow, I’m not running the show here’.”

Poetic Champions Compose

Perhaps the most successful example of Keenan’s world building that I alluded to earlier is the song 'Love In A Snug'.

“I thought you'd like that one alright. That's probably the oldest song on the record, it comes when I was discovering the words but also living it. There's an old, derelict bar in Dundalk called The Snug and I was walking there after a couple of weeks of bowsieism and the story just came to me. I think you understand: I'm not going around, Wildean, with a flower in my teeth, if there's any romance, it's the romance in the realism.”

It's an aspect that a large part of Irish society want to see left in the past. Drinking, hanging out, it's a huge part of Irish culture and Irish literature in particular.

Advertisement

“I couldn’t stay there forever - I was doing too much physical damage! - and though I demystify the idea that I had to play that role to write, it is important. We're living in a time around Dublin where they're trying to sanitise everything and if that penetrates art then it will sanitise that as well and if you allow your soul to be sanitised, it's a mortal fucking sin.”

I interviewed Fontaines D.C. and they spoke against the same sanitisation of Dublin.

“It's dangerous, we're confident people, intellectual, emotional, passionate, articulate. There's no seedy debauchery in revering a certain type of writing, or a certain type of conversation - it's honesty. If the artist has a role, it's to protect a certain element of culture.”

The song also employs a trick Keenan uses a fair bit, the sing-along coda. Is that a natural thing or a calculated move that works well live?

“Repetition in that is like a mantra, and four years ago, I didn’t have a crowd of people that were coming to my gigs, it was one man and his dog.”

And they were lost!

“Yeah! In 'Subliminal Dublinia' the city I’m talking about occupying with original ideas is the city of the self. I’m calling for a revolution of the mind, of the heart and of the soul and I'm writing it for myself, I’m not thinking about an audience but then it so happens on those occasions that you play it live, people catch on to it, and that's why the live thing is so interesting, it's a collaboration with the audience. It's being there in the moment, I'm not trying to write for anybody else, it's all medicine for me.”

Advertisement

Is 'Tin Pan Alley' your 'Tower of Song', a song celebrating the art of song?

“It came about again from direct experience, walking around London in the pissings of rain in an over-sized coat through all these cobbled alley ways,” David remembers. “I saw these really proud down and out men in my head who wrote all those songs for Elvis and Sinatra but I didn’t know their names, it's revering the elders who have left all this work behind.”

A nod to the tradition that you are part of?

“Just me tipping my hat to them.”

‘Good Old Days' seeks to eulogise the past but wants to move on as well.

“I think it's waving at it from the ship as it's pulling out of the harbour. Maybe it's a longing for that sense of community, men coming out of the shoe factory, rows of bicycles in unison, it’s a kind of historical document that appeals to me.”

‘The Healing' – as its title suggests - celebrates the healing ecstasy in music.

Advertisement

“Yeah, as a poultice. The catalyst for this song was my nineteen-year-old brother, who was holding a mirror up to me. He was going through a period of self-destruction. But it's also me saying art is life is love, let it in. You don’t have to be a martyr, you can drink from the well, you don’t have to lock yourself in the tower to be writer.”

Blake’s road of excess might lead to wisdom’s palace but Keenan isn’t totally convinced.

“Self-destructive enterprises stunt growth,” he reckons.

‘Origin Of The World' explores again the Joseph Campbell idea of learning from the tribal elder to help with the journey.

"That's about Ó Maonlaí, that lyric: ‘spirit of a bird , soul of an orphan, release to me wisdom and happy endorphins’. He said to me one day when I was with him - there was a bit of a silence – ‘you know you have to be welcome in your own company before you can be welcome in anyone else's.’ It was as if he could hear my inner dialogue. There's a whole universe in that song. I was in a hotel room in Vienna on my own, coming to terms with falling in love with a friend of mine. I was reading the story of Actaeon in Greek mythology.”

He sees Diana bathing and she turns him into a stag to be eaten by his own hounds. That’s probably Ovid telling us to avoid love.

“It’s the whole enterprise,” says Keenan. “The voyeuristic nature of men and women, the allure of love. If you love someone, you're living in risk because your heart can be confiscated at any moment.”

Advertisement

If you give yourself to love, you’re opening yourself up to be torn apart?

“Beware what sacred pond you look into!”

The danger of love - “Being chased by this beast many young fellas died, Poets digging their trenches have been buried alive” - is being spelled out.

“It’s the element of danger that excites us,” David counters. “Sometimes the hunt is better than the kill, we all love the hunt.”

A Sense Of Wonder

The falsetto at the end of ‘Origin Of The World’ ascends into pure ecstatic sound - “There's things that just can't be said, most things are unsayable” – is Keenan’s explanation. Some things just can’t be explained, but is music the invisible behind the given?

“Songs are a passport to get to that place, that higher fucking form of being. Sometimes I wonder why don't we get to the wail first, to say everything we need to say without words.”

Advertisement

That wail is part of Keenan’s singing style. Lots of singers have their own voice and sing in their own accent but there’s a freedom in David’s voice when it’s in full flow, a sense of a soul untethered.

“That’s the beauty of it, Pat,” is Keenan’s take on it. “It just kind of happened organically. Even as a kid, when I was singing, it was liberation. I think in some of the new songs my voice is definitely changing. I think now I have the ability to do both: I can be calm whereas on a lot of the earlier songs, I was so full of angst, I was wailing and spewing.”

There’s ecstasy of a different sort in the road romance of 'Eastern Nights'.

“Yeah, again it's fact, I met a burlesque dancer from Finland…”

Well, haven't we all?

“It was me the hopeless romantic saying stay here, I'll marry you, you make love to somebody and you've all the notions in the world, stick around, don't leave, but it's not a practical enterprise.”

‘Altar Wine’ is a panegyric to another “fucked-up muse”.

Advertisement

“It’s a celebration of an anarchic young woman, or the image of one. It came about when I was in the early days of falling in love with this person. Maybe the two of us are twins in that song, and maybe I’m taking ownership of the repression she alluded to when she said ‘I’m just like my mother only she hides it better.’ Taking ownership of her repression – sexual, emotional, spiritual – in an act of rebellion.”

‘Evidence of Living' would seem to swipe at a city that doesn’t need another Starbucks or another hotel, but for Keenan there’s more to it than that.

“There's an element of that but it’s also asking if anyone understands these notions, these ideals, does anyone share them? Why can't we just get straight to the point, why do we have to speak in riddles, why can't we embrace vulnerability? It's against dishonesty and cowardice.”

The “stevedore hauling heavy cargo from the bowels of the ship” in ‘Subliminal Dublinia’ is the poet’s lot.

“It's Dublin and holding it in a certain esteem, but also you feel that you're being untruthful by turning a blind eye to injustice on the street. "Hauling heavy cargo from the bowels.” Bringing up the bile. It's also a celebration of the community I found here, but what I'm saying is that after coming through this whole journey, I've gained a deeper self-acceptance. There's the starting point, the last line of the record is "Isn't that a start?"

Advertisement

Beautiful Vision

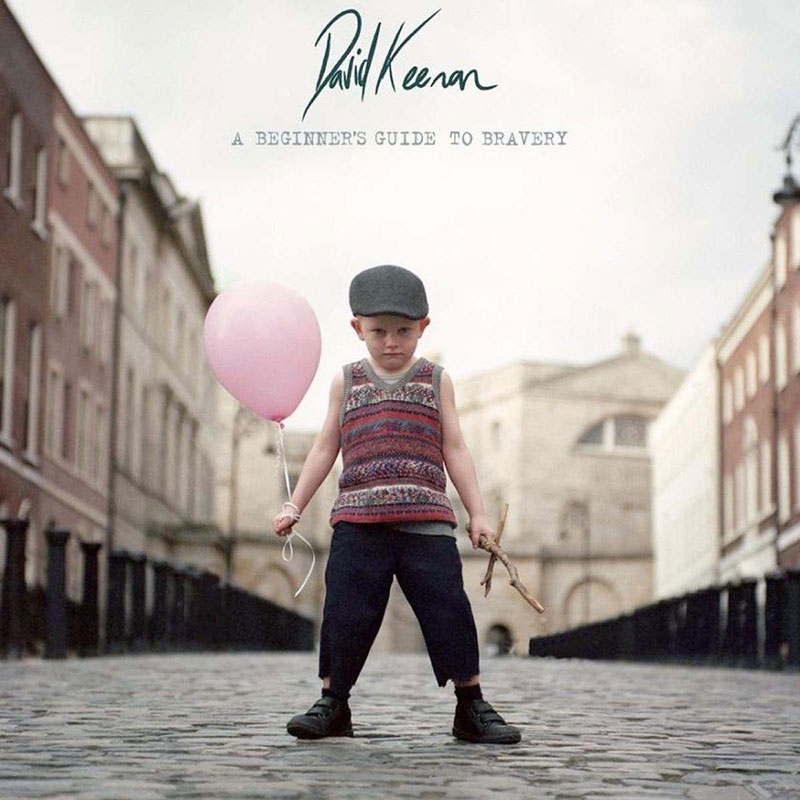

The use of ‘Beginner’ in the album’s title is obviously central to the whole affair. I throw some notions about the young boy on the album’s cover at Keenan, the child is father to the man, etc. but he disagrees.

“I’d say this is more the inner child that is about to set off, the balloon might be his candle, his imagination, that might be a cross, that might be a weapon, he may be a guide, he isn’t taking no for an answer.”

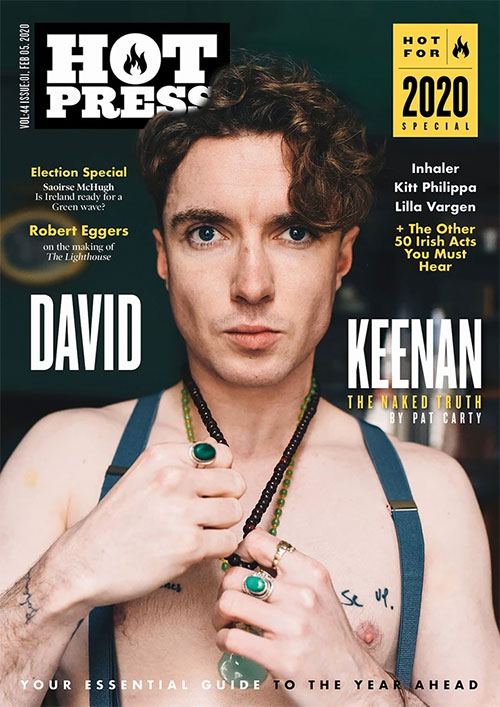

As part of the photo session to go with this article, David was ready to strip down and place his shirt over the back of the chair. It’s an ambiguous image that could be read in a number of ways but the singer refutes the sexual implications.

“That process is about embracing vulnerabilities, our bodies and our naked form is who we are,” he states. “We're living in a world where we're disconnected, if you can't embrace your own vessel, you know... It makes sense to me to stand there with my scars. My arms are bruised - if you listen to the lyrics, there is nowhere to hide. It's openness, and it's truth, this is who I am , for better or worse. The words come out of a certain part of me, the body is another part. If you put a pen on a piece of paper, that's a deliberate act, as is an image of me standing at a window showing my tattoos and my scars with 'Rise up' on my chest - that was literally etched into my chest in a literal act of just hanging on. I clung to life for many, many years, so that little child on the cover maybe points to the act of embracing yourself.”

That’s a good answer, but people may see the image in another way.

“Well, if they had given me a bit of notice, I would have done a bit of work!” he says, laughing the notion off.

Advertisement

As inclusivity is one of his main themes, has he ever deliberately left some ambiguity in the lyrics, to steer away from a strictly man/woman scenario?

“I think - as this is not saying that I'm gender-neutral or anything like that - that I can write from a place of woman and man. Someone said to me - and you don't notice these things - about the line in 'Two Kids' "I run my hands along your forearm, and I see the hairs stand to attention" that the forearm from a woman's point of view is supposed to be one of the most attractive parts of a man. I don't know, I'm just writing as a man, feeling for a woman but also being hurt by a woman. I think that if I ever did reach a place in my life where I wanted to say that I was this or that, well, I probably would, but at the minute, it's not deliberate, it's just how it is.”

The Healing Game

Once the promotional duties are completed, Keenan’s next move is to head to Paris for a few weeks to take up a position as an artist-in-residence. Some might see this as a brave or even foolhardy move when he could be pushing the record further, but he’s not having it

“I have to fill up the well,” is how he explains it. “You have to say I need to do this for me. I’m going to assemble a rag-tag of musicians, finish and record songs so I’ll be refreshed then to return to the tour. At this point, with everyone around me, it’s either take it or leave it, because if this becomes a detriment to my health, then I’m out of here.”

It’s another form of healing then, The Healing might have worked as an alternate title for the record.

“I think in the beginning I was searching for healing and belonging, so it’s a beginner's guide to belonging and healing, but you have to start from the initial realisation and that for me was an act of bravery, and bravery, by the end of the record, is self-acceptance. In this society, accepting yourself is an act of rebellion - to be able to hold yourself and have no judgement and say ‘I'm alright.’”

Advertisement

Keenan declares himself satisfied with the record - “I said what I needed to say,” is his verdict, but when I ask what would constitute a success in terms of how it’s received, he gives me his final word.

“It's a success for me already because of the connection with the band, and the people coming to the gigs. The record is a starting point for me. The themes of the record are all about freedoms. I'd happily sing these songs, I'd happily stand by them. Art is the candle that illuminates the darkness of the soul and it has opened up doors for me that I never would have experienced otherwise.”