- Opinion

- 23 Feb 23

The Hog - Even a Genius Like Samuel Beckett Can Be Banned

He was one of the greatest literary figures of the 20th century, open-minded, inclusive, laugh-out-loud funny – and an extraordinarily brilliant chronicler of the human condition. But apparently that’s not enough any more. Even a genius like Beckett can be banned, as new dogmas take hold…

We’re admirers of Samuel Beckett up here on Hog Hill. It’s not just the ultra-cool Left Bank photos or the quotable quotes. We’ve done the hard yards, seen the plays and read the books.

That a man who strictly rationed his public utterances should now be quoted, often incorrectly, by entrepreneurs, especially in techs and start-ups, and by sports motivators, seems ironic.

It’s not that the quotes don’t have meaning in these contexts. “Ever tried? Ever failed? No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better” is as good as it gets in redefining how we might think about resilience and endurance.

But how did a writer so Spartan of utterance become an icon in this age of needy preening, excessive sharing, uber-revelation and – allegedly – ‘living our best lives’?

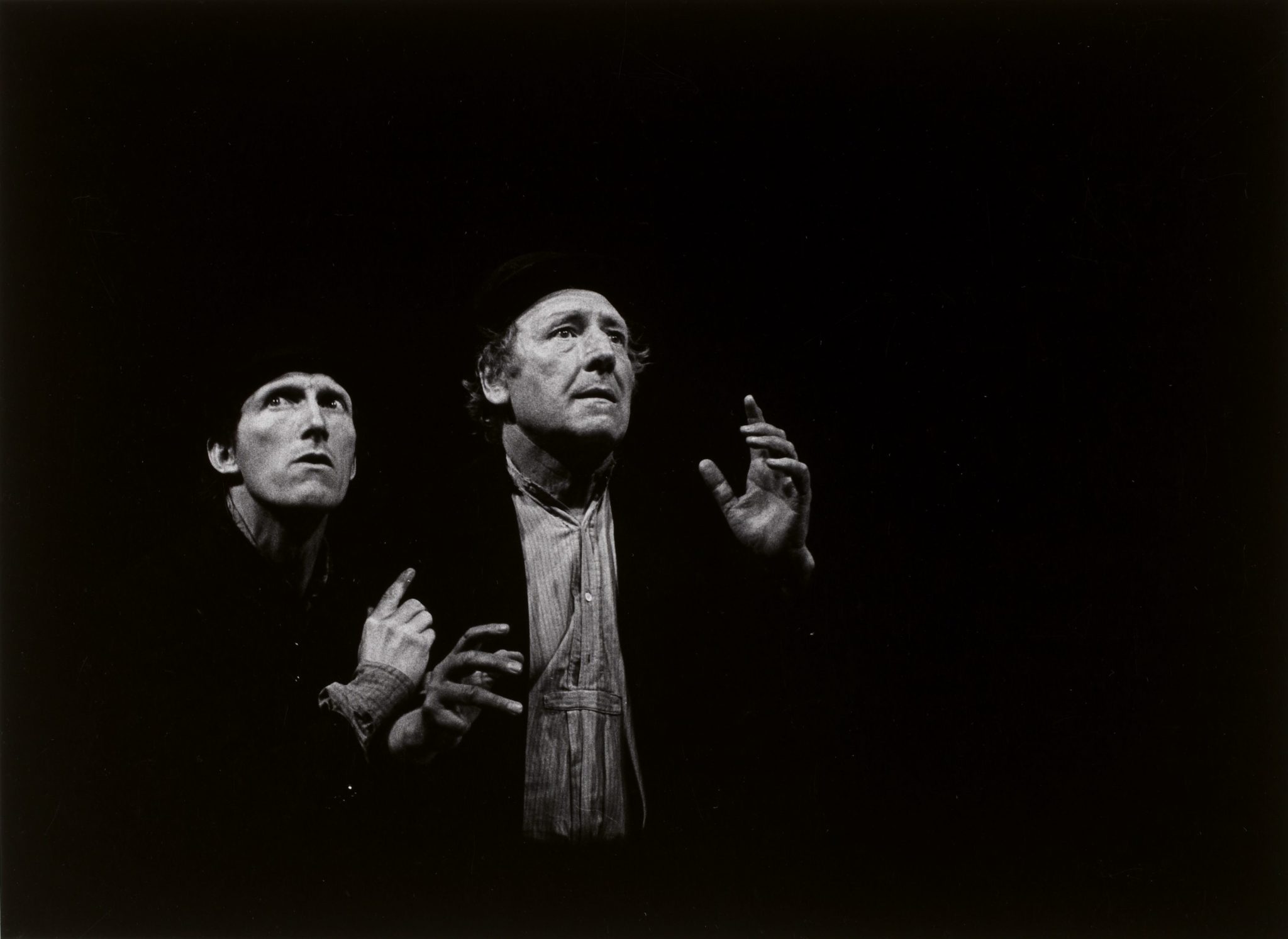

En attendant Godot, staging by Otomar Krejca, Avignon Festival, 1978.

En attendant Godot, staging by Otomar Krejca, Avignon Festival, 1978.AVALANCHE OF NOISE

The very antithesis of 21st century celebrity, Samuel B went out of his way to avoid attention and, in marked contrast to behaviour in our self-promoting, ultra-connected digital world, he very deliberately chose isolation and silence.

In the context of Oscars excess, Beckett’s response to winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in October 1969 is worthy of recall.

Having received the word from the Swedish Academy, his publisher Jérôme Lindon immediately telegrammed Beckett and his wife, who were in Tunisia.

“Dear Sam and Suzanne. In spite of everything, they have given you the Nobel Prize – I advise you to go into hiding.”

“Catastrophe”, said Suzanne as she realised how it would compromise their reclusive lifestyle.

Beckett, of course, was badgered for interviews and comments. To no avail.

He made just one exception, an interview with a Swedish broadcaster. But he agreed to this on the specific condition that no questions were to be asked.

Now known as the “Mute” interview, it’s available on YouTube: Samuel Beckett - “Mute” Interview for Swedish Television – 1969

There he is, looking very much himself – a late 60s Left Bank intellectual, but also timeless. He says nothing. The camera moves around him. They’re by the sea so you hear the waves. And that’s it.

Today, there would be an avalanche of performative noise and comment, of heart and handclap emojis, of upticks.

But Sam was the great under-sharer, and in these overwrought times that makes him not just a role model for all artists and awardees, but a role model for all. The world might be a better place if we were all a bit more like Sam.

Patrick Stewart and Ian McKellen in 'Waiting for Godot' at New York City's Cort Theatre, 2013. Sara Krulwich—The New York Times/Redux.

Patrick Stewart and Ian McKellen in 'Waiting for Godot' at New York City's Cort Theatre, 2013. Sara Krulwich—The New York Times/Redux.MANY CHURCHES AND ALTARS

How ironic, then, to hear that the great Irish writer’s best-known play Waiting for Godot has fallen victim to cancel culture.

It was to be presented at a student cultural centre in the University of Groningen.

Now, Beckett was very precise in his stage directions and often closely oversaw productions of his works.

He specified that the cast for Godot, should be all men. And there apparently is the issue: the cultural centre said it didn’t object to the play being performed by five men, but rather that the casting procedure wasn’t inclusive.

The great British actress Billie Whitelaw was Beckett’s muse, appearing in half a dozen of his plays. She said “he used me as a piece of plaster he was moulding until he got the right shape.”

In Not I, she said, she felt like an athlete and a musical instrument; whereas in Footfalls she “felt like a moving, musical, Edvard Munch painting”.

He was a great writer. His plays are iconic. If you look at his oeuvre as a whole, he was certainly inclusive and egalitarian. And he was even a member of the French Resistance during World War II.

So, on what reasonable basis could a play of his be cancelled?

When Beckett was awarded the Nobel Prize, it was clear which orthodoxies a reasonable person should oppose, at home and abroad.

Fifty odd years later, we live in strident, neurotic and increasingly intolerant times and, far from bringing clarity, the digital age, for all the innumerable oceans of information it has made available, has muddied the waters and the skies.

So called ‘social media’ unleash vast, global torrents of fads and fashions; hand-curated “facts”; and unsavoury behaviours, including far too much neediness, dispute and rancour.

There are, you might say, many churches and altars, myriad texts, orthodoxies and dogmas. They all broadcast into the echo chambers, are all heard by their faithful and, making no concessions to alternative perspectives, increasingly alienate everyone else.

The cattle are herded into the pens and notions of objective truth falter and decay.

BOOK BURNING

The dominant view seems to be that if you’re not with me you’re against me – and any disagreement with my position is a personal attack that must be terminated with extreme prejudice.

Rebels of the 50s and 60s, and onwards into the punk explosion at the end of the 1970s and the emergence of rap, resisted the tyranny of conformity. Do the self-styled rebels of the 2020s want to impose it? Remember, values and expressions may change but tyranny is what it is.

Monty Python’s Flying Circus was an expression of that earlier rebellion.

Its writers and performers were influenced by absurdist and surrealist art and theatre, including Beckett’s work – hence its very British ‘charladies’ discussing Jean Paul Sartre.

Flying Circus was first broadcast in October 1969, just as Beckett was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. How fitting.

A gag line from its second series in 1971 offers a lampoon for today’s censoriousness.

Whenever someone said: “I didn’t expect the Spanish Inquisition”, three fevered Spanish cardinals in red barged into the room, led by Cardinal Ximenez who says, “NOBODY Expects the Spanish Inquisition!”

But of course, absurdist humour or not, the Spanish Inquisition wasn’t a joke. It was deadly serious. A lot of people suffered.

Among its aims, the enforcement of orthodoxy was paramount. Whole populations were intimidated and suppressed, trials were held and thousands of executions were carried out, many by burning at the stake.

Books were banned and burned. It was cancelling, medieval-style.

There have been many grotesque twists as humans struggled to present our carnival of dogmas. History is full of deliberate strategies to isolate outsiders; to banish the unorthodox and those deemed to think differently; and to remove the perceived contamination.

How else can you describe the fatwa against Salman Rushdie?

Or, in the context of 20th century Ireland, religiously-driven censorship (cancellation!) of publications and films, and even book burning?

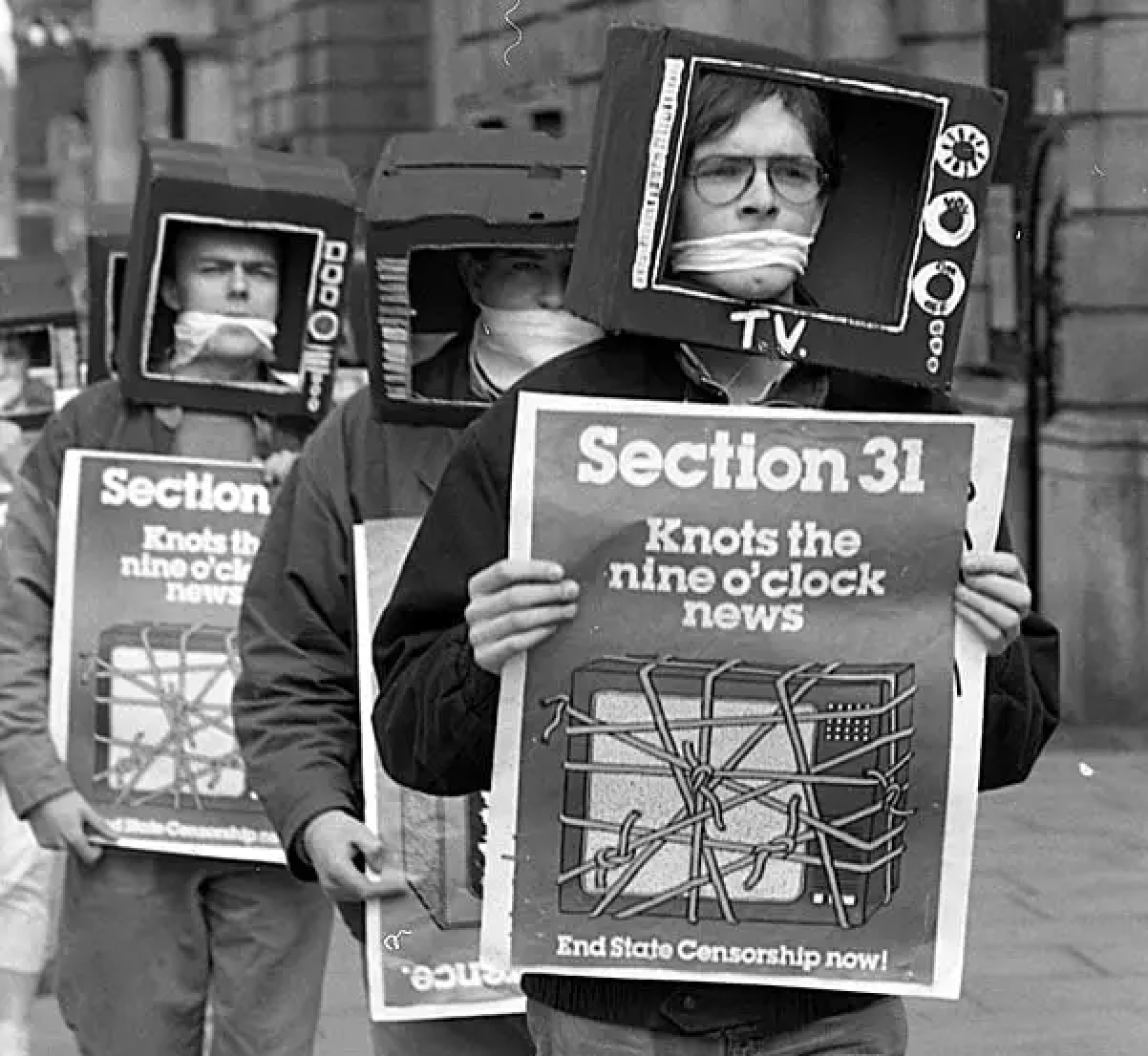

Or the 1976 banning, under Section 31 of the 1960 Broadcasting Act, of spokespersons from specific organisations from the airwaves entirely, including various IRA groupings and Provisional Sinn Féin?

A photo from An Phoblacht depicting a demonstration against censorship and a new video from Sinn Féin about RTE’s latest silencing shenanigans.

A photo from An Phoblacht depicting a demonstration against censorship and a new video from Sinn Féin about RTE’s latest silencing shenanigans.SUP WITH A LONG SPOON

That restriction continued until January 1994, when the then Minister for the Arts, Michael D Higgins, decided not to renew it.

Unspeakable horrors had been perpetrated by paramilitary murderers in Northern Ireland, and in Ireland – things immeasurably worse than writing or uttering words that offend one constituency or another.

But when you contrast the terror that went before with the peace process that eventually followed, wasn’t it better to un-cancel them, to have Sinn Féin and the IRA, and their actions and apologists, subjected to direct scrutiny in the media? To achieve peace by inclusion and force of argument and agreement rather than by exclusion and an attempt to terminate?

As Nelson Mandela said, “If you want to make peace with your enemy, you have to work with your enemy.”

When Beckett had teeth removed late in life, a friend mumbled “It could be worse.” To which he replied: “There’s nothing so bad that it can’t grow worse. There’s no limit to how bad things can be.”

No matter what the campaign or mission, we must not allow ourselves to forget that.

Do what must be done to reach careful consensus.

By all means, stick to your principles. Sup with a long spoon. Hold your nose if you have to. But always remember, persuasion trumps coercion every time.

As Samue Beckett’s work demonstrates, freedom of expression is vital.

• The Hog

RELATED

RELATED

- Opinion

- 17 Oct 25

2025 International Famine Commemoration to be held in Chicago

- Opinion

- 16 Oct 25