- Opinion

- 05 Sep 24

Education is vital. Of course it is. But only if it is approached in the right spirit. It is not just about getting exams and qualifications, but rather about learning the kind of skills that are needed in real life and proper work situations. Oh, and it is also about recognising just how little we know – and opening up generously to what others are bringing to the table…

They say that politicians campaign in poetry and govern in prose. Blue-sky promises founder on the hard rock of reality.

That duality of poetry and prose also captures attitudes to education in Ireland. We value it. Ours is one of the most highly educated countries in Europe and, indeed, the world.

According to the Central Statistics Office, over half the adults in Ireland aged between 25 and 64 have received a third-level education, well above the EU average of 34 per cent.

It’s even higher among younger people. Here, in 2022, over 62% of those aged 25–34 had completed third level. The EU’s target for 2030 is 45%.

Being top of the class certainly helps boost investment and employment. It may also be significant in the global cultural heights we seem to reach.

Advertisement

But it can also mask weaknesses. For example, if we’re that smart why can’t we deliver critical infrastructure?

And for all the high percentages, there’s a serious mismatch between the output of the higher education system and the demands of the labour market.

GROWING STUDENT NUMBERS

Looking at it critically, the focus on education here can be obsessive, even neurotic. For students, all of this is worth thinking about, maybe even thinking deeply...

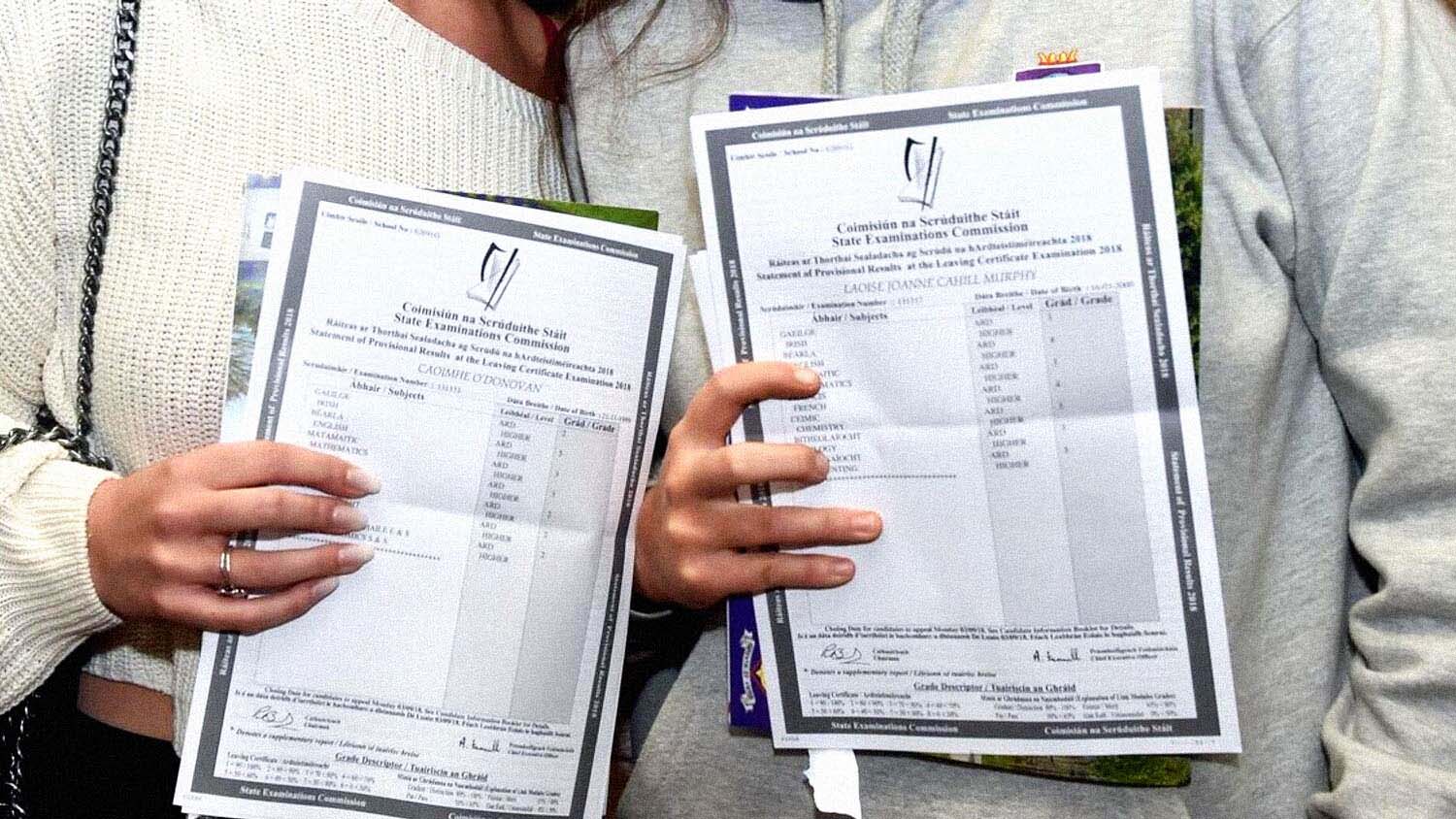

Look at the broadsheets in the last days of August where Leaving Certificate results are parsed and analysed. The rise and fall of points requirements for this programme or that gets far more coverage than the ups and downs of global stock markets.

It doesn’t happen anywhere else.

It reflects a deeply embedded, yet never articulated, pact that Ireland’s chattering classes have with young people: that there is such a thing as a perfect course and that it will be part of your perfect journey in life.

Advertisement

But might it also express our innate love of learning, ideas and knowledge, a dreamscape, a hope and an aspiration?

If so, it’s the poetry.

For the prose, turn to student satisfaction with their school and college experience, the perceptions of academics of their student intake and the views of employers on graduate capacities and preparedness for the demands of the workplace.

It’s not all harsh, but a whole range of new notes are added to the page.

For example, one research project surveyed first year students in DCU in 2018. The results are still very relevant.

Most (83%) believed that the Leaving Cert programme had prepared them well to persist when learning was difficult, be well organised (83%), be self-disciplined (75%), manage their time (72%) and cope with the pressure of heavy workload requirements (75%).

Advertisement

However, only one in four – that’s a miserable 25% – thought that the Leaving Cert had prepared them well to use technology to improve their learning, to interrogate and critically evaluate information or ideas, to compare information from different sources or even to identify the real sources of information.

Only three in ten – 33% – felt the Leaving Certificate prepared them well to explore ideas from a number of different perspectives.

These are all critical skills to a successful and fulfilling experience in higher education and, unsurprisingly, many academics complain at how much time (and energy) goes into helping students develop them – a complaint that increases in vehemence in parallel with growing student numbers and digital immersion.

NO CONTROLS OR STANDARDS

That’s just the study side. But higher education encompasses so much more.

For those entering from school, it’s the pivotal period in transitioning to independence, to the identity they’ll carry for much or all of life.

As well as new ideas and knowledge, there are new friendships to be made, streets and districts to be explored, new experiences to be had.

Advertisement

It’s the last sustained period in which young people have the time to range far and wide, to freely generate a vision for themselves and the world; to espouse ideals rather than practical realities; to dream the dream and live the poetry and song, without the chilling winds of the real world and its complications and compromises.

But it doesn’t necessarily work that way, as we learn from the Higher Education Authority’s annual student survey.

Yes, there’s some good news.

More than four in five students would go to the same institution they attended if they had their time over.

• Over half rated the general quality of interactions in their institution as high.

• Three in four believed their experience contributed to their knowledge, skills and personal development “quite a bit” or “very much” in thinking critically and analytically.

• Three in five think that their college put sufficient emphasis on supporting students to succeed academically.

Similar numbers think their college experience has helped them develop job or work-related knowledge and skills.

There is also a 9% increase in students reporting having someone in their university they can talk to about their day-to-day problems.

Advertisement

But there’s also bad news.

Only one in five reported that they regularly discussed course topics, ideas or concepts with academic staff outside of scheduled class, tutorials, labs or studios.

Almost 37 per cent of students said they’d seriously considered dropping out of college. The figure is 5% higher among postgraduate research students.

They cited financial pressures, long commutes, high rents and a range of personal reasons and external stressors, especially to do with health, and mental health in particular.

Traditionally, Official Ireland fretted over alcohol abuse in higher education. But in the 2020s young people drink less but take more drugs.

Cocaine, cannabis and synthetics are everywhere in Ireland. Higher education institutions are no exceptions.

A particular concern is that, unlike alcohol, there are no controls or standards with illegal drugs. You could be taking anything.

Advertisement

The drug testing provided at Electric Picnic and other festivals happens for a reason.

IT SHOULD BE CHALLENGING

As regards the academic experience, as well as coping with the scale of the institutions and the degree to which you won’t be spoon-fed by lecturers, students now also have to navigate new territories and potential tyrannies.

Being ‘cancelled’ is a serious issue in higher education. It shouldn’t be. It’s a modern equivalent of book burning. They do it in Iran, Afghanistan and far right Alabama. Is that how we want to be?

Social media may liberate young people in many ways but you’re always on show and on alert.

They have hugely increased the pressure to be perfect and live the perfect life – as if that were ever a remotely reasonable expectation – but also to be angry, intolerant and aggressive.

Many academics also argue that social media and digital technology have compromised both students’ attention spans and their ability to deep-dive into a subject.

Advertisement

On the one hand, the amount of available information is infinite. On the other, it is curated by algorithms that chase what a person seems interested in rather than a broad picture of a topic.

And now we have AI, already in the wild and creating massive issues for teaching and testing, not to mention writing and communicating.

These issues all undermine an education project which purports to be about nurturing inquiring minds, questioning, testing the boundaries, broadening perspectives, learning about other people, deepening understanding, embracing culture and diversity, and promoting knowledge rather than information (and especially disinformation).

It shouldn’t be easy: it should be challenging, a stretch, an opening up. And not everyone will succeed. It wouldn’t mean anything if everyone did.

But it should also be caring and considerate. There are vulnerable people all around. There is loneliness and heartbreak. We may need help ourselves. But what is certain is that we can help others.

In the meantime, let’s have the poetry. The prosaic can wait!

You can read the full Student Special in the current issue of Hot Press – out now: