- Opinion

- 24 Nov 20

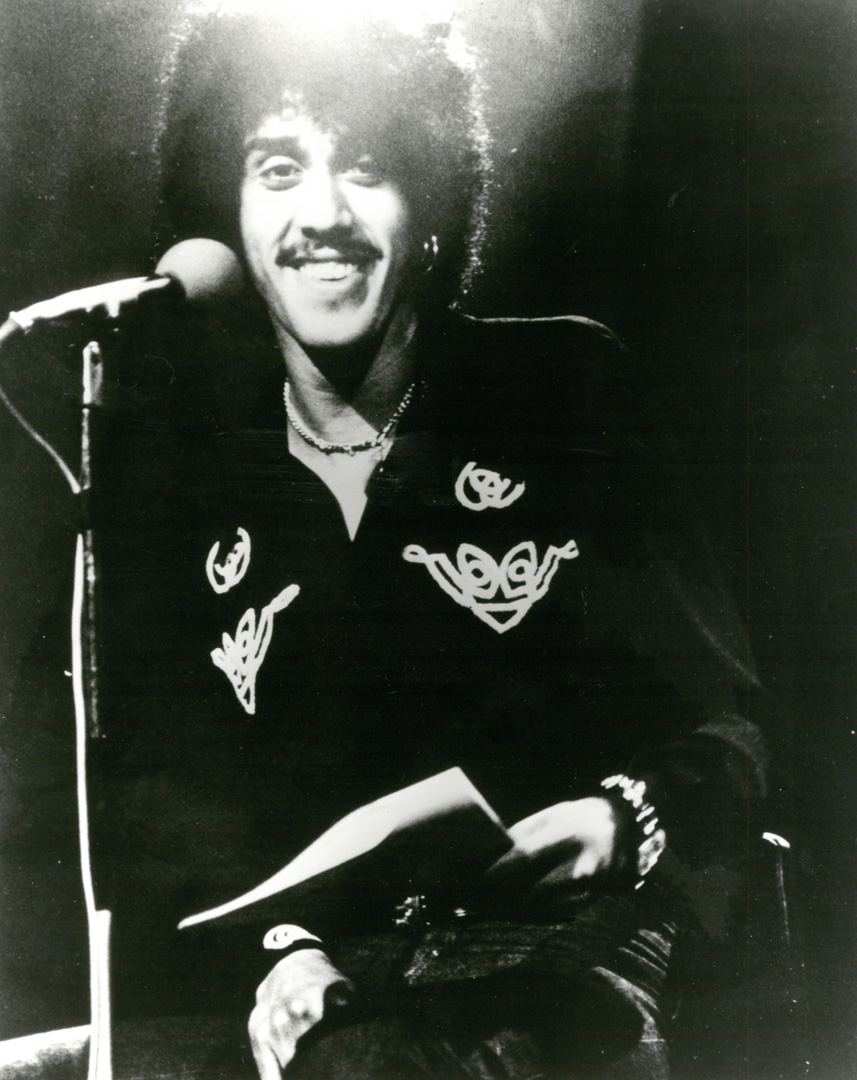

The Message – Philip Lynott: Songs For While I'm Away – "A film that is warm, generous and hopefully healing in its effect"

The new Philip Lynott: Songs For While I’m Away documentary strongly resonates with Black Lives Matter, and is set to win him a whole new generation of fans.

I remember when I got the first call about the idea of doing the definitive documentary on Philip Lynott, one that would tell the true story of Ireland’s legendary, brilliant, magnetic, rock star.

It was in the wake of the success of 2015’s Amy that the idea started to get long, Phil Lynott-like legs. That fine and very moving film about the rise and shockingly sad demise, of the extraordinarily talented Amy Winehouse had made people in the entertainment industry freshly aware of just how powerful and emotionally charged a movie about a major music icon could be – all the more so if the story had a tragic ending.

That Philip Lynott seemed like a suitable candidate for the documentary treatment was hardly surprising. For a start there were the tunes: he wrote a couple of poker-hands worth of utterly memorable pop songs, many of which had so far failed to realise their ultimate commercial potential. As with Amy herself, his extraordinary charisma and good looks were a factor too: it was not hard to imagine a whole new generation of rock fans, and women especially, falling in love with Philip Lynott, and with his and Thin Lizzy’s music.

This would be the story of a working class Dublin kid making it as a rock ‘n’ roll star against the odds. More tellingly, he wasn’t just any old rock star. A black Irishman, he was truly one of a kind. And thus, he was the sort that was referred to not once but twice – and some might argue, in the eyes of British Tories, three times – in the infamous slogan that appeared regularly in the windows of digs, flats, apartments and houses that were being rented in the UK in the years after the war: No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs.

Ticking the boxes was easy. He was born to a single mother. He had been separated from her as a result of societal pressures. He had a decidedly unconventional upbringing. He had always shown an exceptional love for the women in his life – from his grandmother Sarah through to his daughters Sarah (again) and Cathleen.

There was his belief in himself as an Irish romantic poet. His marriage to the glamorous Caroline Crowther, daughter of the TV star Leslie Crowther.

The mischievous grin that said there was always more to it – whatever ‘it’ might be at any given time.

The cosmic wink. The thumping bass. The Spiderman shapes. The unique rapport that he enjoyed with fans and believers. And, after the ball was over, there was the success that his mother Philomena Lynott uniquely achieved in her own right following Philip’s death.

He was a phenomenon.

Phil Lynott.

Phil Lynott.So a documentary was on. There were false starts. Asia Kasadia, the director of Amy, was mooted to take on the project. It was an intriguing possibility, but didn’t pan out. Directors, who I felt would do the job well, were talked about, but also fell by the wayside. There were moments when, observing from the outside, you might have imagined that there was some kind of jinx involved.

As often as not, making a film is a marathon, not a sprint. David Lynch started casting Eraserhead in 1971 and it was finally released in 1977. Francis Ford Coppola took five years to make Apocalypse Now. Short cuts are hard to find.

In Ireland there are possible tax breaks to be explored. Funding sources to be wooed, including Screen Ireland. Other investors to be convinced. Potential broadcast partners to be spoken to. A bad break or two and the concertina starts to stretch. Sometimes it is impossible to squeeze it back into shape, to get the music flowing.

Finally, around the start of 2017, word came through: Emer Reynolds was on board. A multiple award-winning film editor, Emer made her directorial debut with Here Was Cuba, in 2013. That widely praised film was followed by The Farthest, a documentary about the US Voyager programme, which won the Audience Award at the Dublin Film Festival in 2017. You could discern, in the lyrical, poetic feel of that documentary, her credentials for making a film about an Irish dreamer, musician and poet.

Emer Reynolds hadn’t the remotest interest in painting a graphic, sensationalist picture of what went wrong in the life of Philip Lynott. She wanted to take a far more measured approach.

Bring your own natural empathy to the table. Build trust. Focus on the songs and, in part at least, allow them to tell the story. Find the best possible interviewees to give a rounded portrait of the man and his work. Dig out the kind of historical archives and footage that long-standing fans would love and new ones might swoon over.

And above all, respect the unique character of the man: his charisma, his drive, his charm, his ambition, and his desire to find the words that would express the complexity of the experiences he himself had been through.

Underneath, of course, there would have to be recognition of the things that gnawed away at him: that created feelings of insecurity, loneliness, and in the long run, loss of self-esteem, dependency – and finally despair. It would be impossible to make a film about Phil Lynott and not refer to songs like ‘Gotta Give It Up’.

But ultimately, in Philip Lynott’s case, there is room for a strong counter-current – a feeling that what happened was as much an aberration, or an accident of circumstance, as anything else. That events might have turned out differently. That, on balance, the ballad of Philip Lynott – archetypal Irish rocker – can be sung now as a bittersweet story rather than an angry one, laced with an aching sense of loss, of course, but loaded still with an awareness of the fact that he was indeed a hugely inspirational figure, who played a vital part in the evolving story of modern Ireland – and who remains widely and deeply loved not just here but around the world.

The plan, naturally, had been to release the film first in his home country, where he was so revered, in the hope that it would gather momentum and acclaim in Ireland, which would then carry it into the international arena on a high. But the pandemic – and the decision taken by Government to close cinemas – made that impossible. Where it has been seen already, for example in Sweden and the UK, it has been very well received. Fans have shown their appreciation.

They will in Ireland, too, and in big numbers once people are allowed back into cinemas. Hopefully that will be for its latest planned release date, on December 26th. I am sure that Emer Reynolds, among others, is keeping her fingers crossed.

We all know that the pandemic is a curse, but for anyone who was in the throes of getting a big project out into the marketplace, it is doubly devastating, to see three years of work being cruelly derailed. The effect is that Songs For While I’m Away has been denied the kind of hoopla and hype in the US that might have surrounded it in normal times, and there is a concern that it might not find its audience quite so easily there now.

There is no doubt that the story of the first great Black Irishman – and the way in which he was embraced by the chronically pasty-faced Irish – has a potentially potent resonance in the here and now of Black Lives Matter. But the question remains: can they get that message across in the right way to the greatest possible number of people? That is a big ask.

There are other regrets. Central among them, from the point of view of someone who helped a small bit along the way, is that the almost five years it took to get from the original discussions to the finishing line saw the loss of two key figures in Philip’s life: his mother Philomena and his long-time consigliere Frank Murray.

To an extent, this is in the nature of making documentary movies. Time is a brutal master: it waits for no man or woman. Frank died suddenly almost four years ago, at the tail end of 2016. He would have been a great interviewee because he knew Philip better, for longer, and more intimately than perhaps anyone else on the planet. I’d have loved to hear his voice and to have pondered his wise words, his wit and his eloquence one more time. But there is no arguing with the toll that death takes, and the havoc that it wreaks, especially when it is sudden. That he is missed here by those who knew him is an inevitable catch-in-the-throat factor.

Philomena, to whom Philip had meant so much, for so long – and who had dedicated the final thirty-plus years of her life to keeping his memory alive – would have loved to see the film, and to revel again in the spotlight cast by the love and appreciation of so many for Philip and his work. But illness caught up with her, and there was a sad moment when it became clear that she would not be well enough to play her part in shaping the story.

Philomena is in there, and it is adroitly handled. It is part of the charm of the film that, in the end, what you feel more than anything else is not the differences that she might have had along the way with Philip’s wife Caroline, which were famously written about with so much relish in the tabloids, but what they had in common – in that for a period of time at least, the great Irish rocker was at the centre of their respective lives.

On that theme, an extraordinary note is struck by Caroline in Songs For While I’m Away, when she says that she was really only getting to know Philip. She was very young at the time. Only eight years passed between when they got together and his death. But of course they had two children together, Sarah and Cathleen, who also appear in the documentary – and who take the opportunity to pay tribute to Philomena.

This is a mark of the sensitive, careful approach taken to what might have been a difficult or even contentious subject by Emer Reynolds. She brings the gentleness that is characteristic of her personally into her work. And the end result is a film that is warm, generous and hopefully healing in its effect.

There is so much great music, and there are so many wonderful images of Phil – as Emer prefers to call him – Lynott in the film that it should, and most likely will, win the quintessential Irish rock star new fans aplenty. He remains a seminal figure in Irish music, and it is vital that his legacy should live on, and inform everything that happens in rock ‘n’ roll here as we continue to evolve and change.

I can imagine what Phil would have felt about the emergence of a new potential superstar like our other cover star this fortnight Denise Chaila – and indeed about her musical partners God Knows and MuRli. He’d have been proud of the part he played personally in changing Ireland. He’d have been curious to hear what they have to say, and also the music that they are making. But most of all, he’d have been competitive. He’d have wondered could he go one better. Capture the new zeitgeist. Be, still, the one that they all looked up to.

Perhaps, even in death, he has achieved that. For fans of Philip Lynott, it is a thought that’s worth holding firmly onto. Some people really do change the way things are. Let us hope that Denise Chaila and her Limerick buddies achieve a similar feat, in the long run, to the great Philip Lynott.

That would be the ultimate victory for us all.

* * * * *

Main Image: This unique Philip Lynott art-piece is an original linocut print by Hot Press’ illustrator extraordinaire, David Rooney. It was produced specially for the Hot Press Awards in 1986, with the limited edition art-print being presented to that year’s winners, in what was the year of Philip’s untimely death...

* * * * *

The new issue of Hot Press, featuring flip cover star Philip Lynott, is out now. Order a copy of the new issue below: