- Opinion

- 03 Apr 24

The Pogues: 'Dark Streets of London' – 40 Years On

It was in the crucible of punk rock in the late 1970s that The Pogues first started to take shape. But there was still a long road to travel before the outfit we know and love made their astonishing debut album, Red Roses For Me. Here, Jem Finer of The Pogues, Shanne Bradley of The Nips, Trish O’Flynn of Shillelagh Sisters, Dave Robinson of Stiff Records and Pogues biographer Ann Scanlon guide us through the streets that gave birth to The Pogues in late 70s/early 80s North London – and the recording of their iconic debut single, ‘Dark Streets of London’.

December ’23 Tipperary

In the eaves of the Church of Saint Mary of the Rosary in Nenagh, jackdaws roosted, their little black frowning crowns seeming to mumble: chak-chak, chak-chak, chak-chak. Wind howled. Rain spat. Television crews were setting up their metal and glass menageries, journalists and photographers shuffled for position, while security personnel manning the wrought-iron gates, opened them every few minutes to allow musicians and singers early entry to the church, to rehearse and soundcheck.

People wandered in and out of the side-porch; inside, under the sloping roof of the sacristy, assembled an assortment of Ireland’s finest musicians grabbing coffee, chatting, learning songs and being directed by event organisers through the ceremony’s time-table. In the church itself, to the right of the altar, the band Cronin were setting up their kit. Glen Hansard and Lisa O’Neill were running through ‘Fairytale Of New York’, members of Cór Chúil Aodha, the mighty choir founded by Seán Ó Riada in 1964, now directed by his son Peadar Ó Riada and including Seán O’Sé whom Shane adored, clutched red songbooks and nattered quietly under the shadow of the mammoth church organ.

Outside, large crowds were beginning to gather. Meanwhile, on Denzille Lane in Dublin 2, Shane MacGowan’s coffin was being transferred from the glass-sided horse-drawn carriage that had escorted him from South Lotts Road, down Pearse Street and onto Westland Row, to a motor hearse that would take him on the longer journey he had made countless times before, from Dublin to Tipperary. The cortege led by the Artane Band and a lone piper passed thousands of mourners who lined the streets blessing themselves, calling out ‘Shane!’ and throwing flowers. Reporters gathered tributes from people in the crowd. Dermot Doran told The Guardian, “He was one of the greatest Irishmen. He embodied the soul and spirit of the country. He embodied who we are, warts and all, and expressed it magnificently. We’ll always be proud of Shane, just like the English are of Dickens.”

As the hearse travelled to Nenagh, mourners funnelled into the Church of St. Mary of the Rosary desperate to claim a seat, or standing space if necessary, to witness the epic historical event of Shane MacGowan’s Requiem Mass. When Shane’s coffin, bearing the Irish tricolour, was carried into the church, a sudden hush over-rode the burr of the congregation, then the choir began singing ‘Críost Liom’ and local parish priest Father Pat Gilbert welcomed the congregation, and all those watching online or listening on radio.

Shane MacGowan funeral in Nenagh, Tipperary. Friday 8th of December 2023. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

By now, an extraordinary cast of characters had assembled; they were dotted about the Church, among them Uachtarán na hÉireann Michael D. Higgins, Finbar Furey, Gerry Adams, and Johnny Depp. Even amid the pervasive sadness, the funeral turned into a kind of musical feast. Glen Hansard and Lisa O’Neill performed ‘Fairytale Of New York’; Imelda May and Declan O’Rourke sang ‘You’re The One’; Mundy and Camille O’Sullivan performed ‘Haunted’; former Pogue Cáit O’Riordan and John Francis Flynn sang ‘I’m A Man You Don’t Meet Every Day’; and Nick Cave crooned ‘A Rainy Night In Soho’ – all, more or less, backed by MacGowan’s last band Cronin (a 15-track album, which includes guest appearances from Spider Stacy and Jem Finer, will be released at some point), Colm Mac Con Iomaire and John Sheahan, in addition to George Murphy, Liam Ó Maonlaí, piper Emmett Riordan and Sharon Shannon.

On the spot, and in the moment, one wondered what it must be like for those who were closest to him – his wife Victoria Mary Clarke, his father Maurice and his sister Siobhan. It must be remembered that amidst the outpouring of public grief, there exists a small core who deeply loved, and were greatly loved by, this extraordinary man of letters. At ceremony’s end, Victoria and Siobhan delivered a pair of mighty eulogies to their beloved husband and brother.

And then a quartet of The Pogues – James Fearnley, Spider Stacy, Jem Finer and Terry Woods – once, of course, young people who challenged political and musical establishments, men who Tom Waits memorably described as ‘sailors on shore leave’ – were on the altar, looking fantastic in winter greatcoats. After reading aloud a touching letter from Pogues drummer Andrew Ranken, they performed ‘The Parting Glass’. Leaving the altar, Spider lightly touched Shane’s coffin, the last meeting in this world of the two old muckers, the erstwhile Noodles and Max of North London.

’76 North London

Let’s go back there, shall we? To trace the side-alleys of the long and sometimes winding road that took The Pogues from their genesis in the punk era to the recording of their first single, the inimitable ‘Dark Streets Of London’ in 1984.

We are retreating. Past The Popes’ Crock Of Gold. Past The Snake and its wonderful duets with Sinéad O’Connor and Máire Brennan. Past The Pogues’ optimistic swansong Hell’s Ditch. Past the often overlooked Peace & Love. Past the global phenomenon of ‘Fairytale Of New York’. Past the orchestral masterpieces of If I Should Fall From Grace With God. Past the sacred perfection of Rum, Sodomy And The Lash and Poguetry In Motion. Past the divine debut album Red Roses For Me. Even past when they were called Pogue Mahone, back to before they ever existed. Way, way back to the King’s Cross and Camden of the late ’70s, to a young Shane MacGowan holding court in the upstairs bar of The Cambridge on Charing Cross Road, working at Rocks Off in Soho, serving porter at The Griffin by Charing Cross.

I meet The Pogues’ first biographer, Ann Scanlon, outside Bradley’s Spanish Bar, just a few doors down from where Stan Brennan’s record store, Rock’s Off, once stood and MacGowan once worked, on Hanway Street off the Tottenham Court Road. We nip in for a swift one, before Ann leads me on a trail of old Pogue haunts.

Ann Scanlon

We wander past The Black Horse in Rathbone Place, through Georgian Bloomsbury, past WB Yeats’ old gaff on Woburn Walk, down to Burton Street, lingering outside Number 32 – the hallowed ground, in which Shane MacGowan, Jem Finer, Spider Stacy and James Fearnley all at one time lived, wrote and made music. For many Pogues fans, it is Ground Zero, where it all began, a much-mythologised source. I read somewhere that MacGowan, when asked about Burton Street, replied in typically mischievous fashion, “It was a road and a lot of buildings.” The man wasn’t lying. We sip halves in the Norfolk Arms in nearby Leigh Street, a one-time Pogue haunt, then head around the corner to The Boot, on Cromer Street, where the tour bus used pick up a sometimes-reluctant MacGowan to go gigging.

In The Boot, Ann tells me of hearing Pogue Mahone for the first time. Hearing ‘Dark Streets Of London’ on the radio turned herself and her brother into slack-jawed gawkers – a song like that, on the radio and sounding punk and Irish! She says that growing up in Lincolnshire, when her family were going to Ireland on holidays, her Mayo-born parents would tell her – ‘We’re going home,’ and she would think: ‘If that’s home, where is here?’.

“You feel”, she tells me, that “your real life is taking place elsewhere.”

Then a band such as Pogue Mahone turns up, apparently out of nowhere, possessing incredible songs that are reflective and intuitive of the experience of being Irish in London, and capturing the world of that audience hook, line and sinker.

On the Zoom-line from Cambridge, formerly of rockabilly punk outfit the Shillelagh Sisters, Trish O’Flynn sets the scene for what it was like in London in the early-’80s.

“It was a very hard time to be Irish in London,” Trish says. “Even second generation, the prejudice was huge. My parents were very involved in the Irish community and the Irish Centre in Camden and I their philosophy was, ‘Keep your heads down, get on with it, support us, support the community, we’ve just got to fight through this and encourage our kids to do better,’ as immigrants do.”

The late Pogue Phil Chevron observed to another Pogues biographer, Carol Clerk, that second generation London-Irish, “Grew up learning Irish dancing and hearing Irish songs on pub jukeboxes. They needed physical manifestations of Irishness… The Pogues arrived with the epiphany of writing both within and against the tradition.”

Trish recalls that during that period, many second-generation Irish were educating themselves, reading Irish literature – Shaw and O’Casey – embracing their Irishness and raising their heads above the parapet. Her band The Shillelagh Sisters possessed “a very strong political edge to it because you know, the times were in fracture – the miners’ strike, the hunger strikes in Northern Ireland. I mean, it was a really crazy time to be Irish or second-generation Irish in London.”

In 1975, Shane MacGowan formed a band called Hot Dogs With Everything, with his friend Bernie France, with whom he’d attended Hammersmith College of Further Education. In a 2018 interview with Ann Scanlon, France explained that, “When we were at college, we just had the feeling that all good music was finished, it was over. We would look back at stuff, we listened to ’60s beat groups like The Troggs, Them, The Pretty Things – for us, all the good stuff was in the past.”

France joked that they didn’t ruin the band by playing any gigs or releasing any songs.

In April ’76, Shane attended the Nashville Rooms in West Kensington to watch Joe Strummer’s 101ers. Fortunately, he got there in time to catch the support act, The Sex Pistols. In 2000, MacGowan described to the The Irish Times what it was like seeing Johnny Lydon for the first time . “This little red-haired Paddy up there pouring beer over his head and sneering at the audience shouting insults at him,” he recalled… “I thought this was the pop band I’d been waiting for all my life.” He became a constant at the Pistols’ erratic gigs, becoming a face of the scene, photographs of him featured in Sounds and the Evening Standard. Meanwhile, a review of The Clash at the London ICA, published in a November issue of NME, with the sensational headline, ‘Cannibalism At Clash Gig’, featured a photograph of him with blood flowing from his head. The following month, the first and only issue of MacGowan’s fanzine Bondage featured The Sex Pistols on the cover.

’77 The Nips

All weekend, I’d been trailing Shanne Bradley, founder of The Nipple Erectors, in a friendly haze, across North London. We met briefly in Maddens in Finchley on Friday night, crossed paths the next evening at The Dublin Castle in Camden and agreed to meet on Hampstead Heath the following day.

As good as her word, early on Sunday morning, the striking figure of Shanne strides up to me at the foot of Parliament Hill and we go wandering across the Heath. Shanne is still punk, still rebellious – in addition to being self-deprecating, impish and fine company. She tells me that her first band were called The Laundrettes. “Because we just made a noise like a laundrette,” she laughs.

In 1976, Shanne formed The Nipple Erectors (later shortened to The Nips), in her bed-sit in Drayton Park, beside the Arsenal football ground.

“I met this character called Shane MacGowan,” she recalls. “I’d seen him around various gigs – The Clash at the ICA and Royal College of Art, The Jam at the 100 Club. I said to him, ‘I’m forming a band, would you like to audition for it?’ He went, ‘Yeah, it’s my dream. I’ve always wanted to be in a band’. So, he came around to my place on Stavordale Road, knocked on the door, and just dived in and rolled around on the lino, doing this Iggy Pop impersonation. And he was just brilliant. ‘Yeah’, I said, ‘you’re the frontman.’”

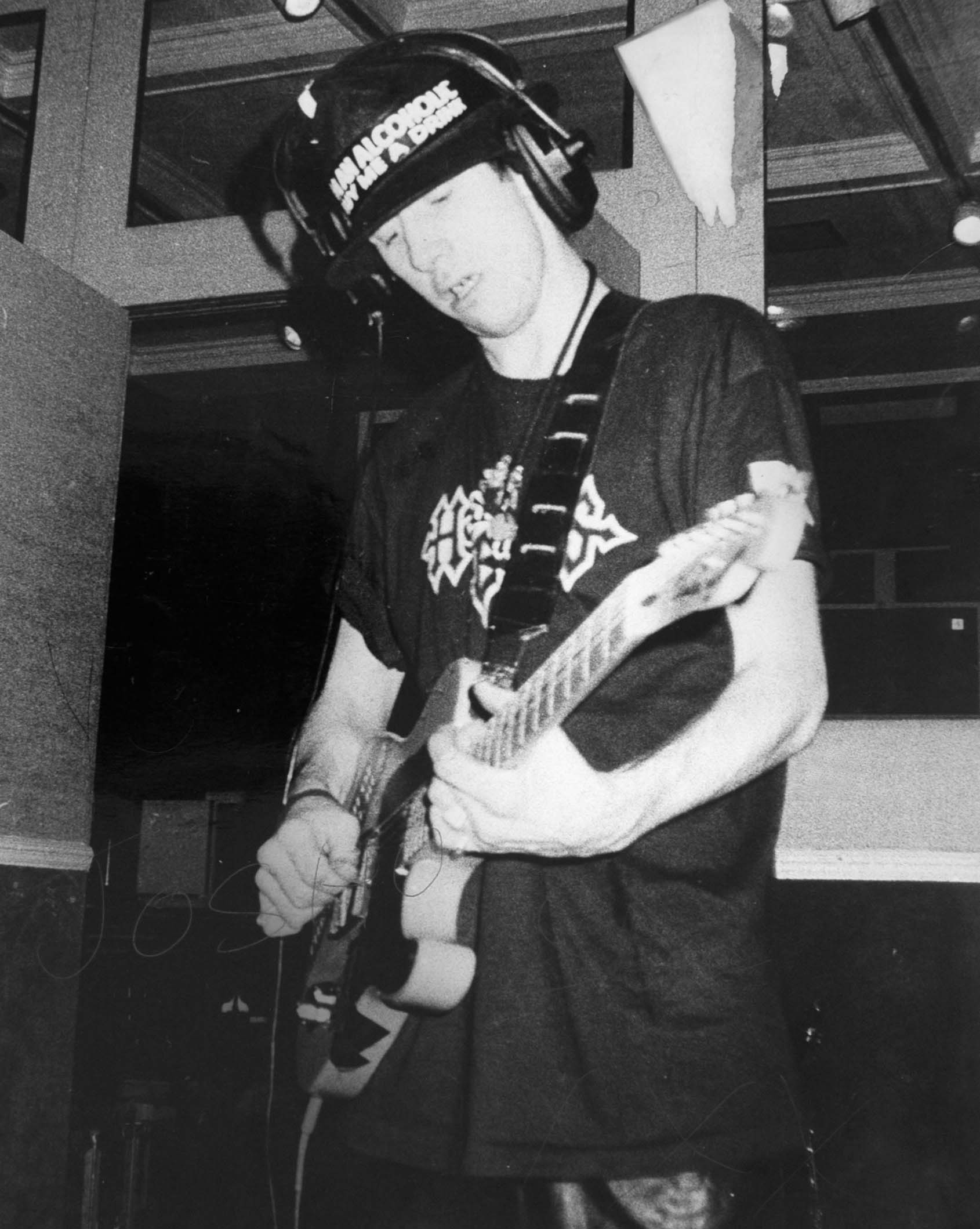

Shane MacGowan. Photo: Pyke

The assembling of The Nips was pure punk, Shanne tells me. “I knew this guy, Roger (Towndrow), who was an artist, and he’d just finished college and had a guitar. And then we’re at the Roxy – we needed a drummer and Captain Sensible was there. And he said, ‘I just met a guy in the bar. He looks good. He probably will be suitable. He reckons he plays and he’s named Arcane Vendetta’, so we got him in – but he just played a biscuit tin.”

The first Nipple Erector gigs were in the autumn of ’77, not long after the first issue of Hot Press hit the streets in Dublin.

“For the first gig at the Roxy,” Shanne explains, “our drummer got a toy drum-kit and I’d got a slightly better bass because I had a toy bass in the beginning. The audience consisted of Paul Weller, his mom, dad and sister; Captain Sensible and a lot of our mates – that was probably it. Sensible brought some gladioli and showered me with them and Shane poured a pint of beer over me as a baptism for my first gig!”

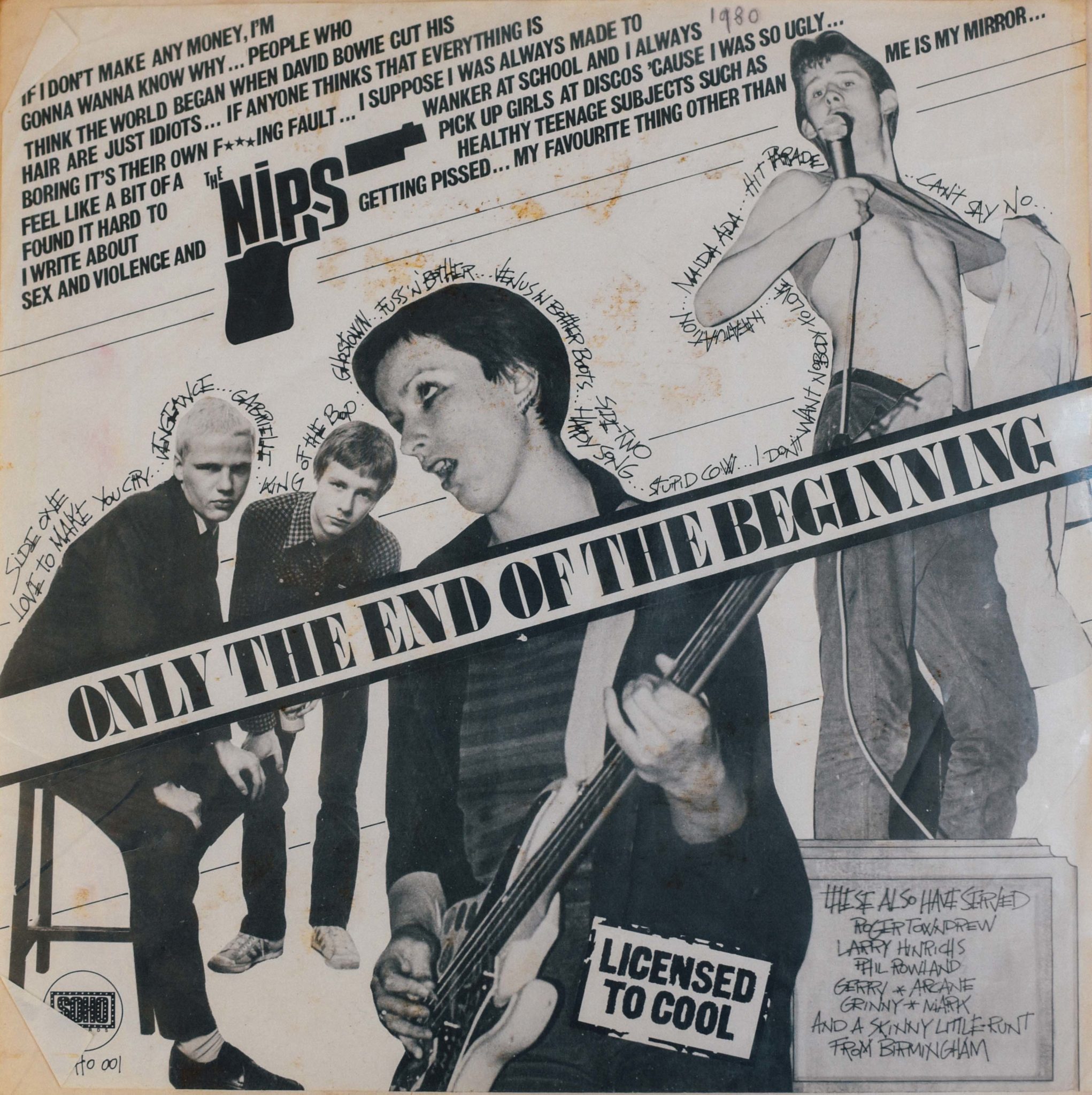

The Nipple Erectors were up and running, and began gigging across London. In October 1978, they would play The Harp in Belfast, with one Terri Hooley promoting. The band recorded six tracks in a reggae studio in Belmont Street, opposite the Roundhouse in Chalk Farm. The single ‘King Of The Bop’, with ‘Nervous Wreck’ as the b-side, came from those sessions, produced by Stan Brennan and issued in early summer 1978 on Soho Records, the label he ran with Phil Gaston.

Further singles – ‘All The Time In The World’ and pop banger ‘Gabrielle’ – were issued on Soho before their fourth and final single ‘Happy Song’ was released in 1981 on Test Pressing Records. However, by that time, The Nips – now including a recently recruited guitarist, one James Fearnley – had reached the end of the road.

’80 Burton Street, London

When I tell Shanne about visiting Burton Street the previous evening, she gently chides me. “You should have brought me, I lived there,” she says.

She did. As did a gaggle of future Pogues – MacGowan, Finer, Fearnley and Stacy, who had moved there en masse with his band The Millwall Chainsaws in 1979.

By way of detailed correspondence, Jem Finer sets the scene for me.

“I was offered a room in a house in Burton Street sometime in the autumn of 1978. I had my name down on a list with an organisation called SCH – Short Life Community Housing – based in Cromer Street. They had some deal with the council whereby they licensed unused properties on a short-term basis and rented them out cheaply to people on their books. I called them every few weeks and one day they said there was a room, in 32 Burton Street, if I wanted it.

“I was living in a squat in Kentish Town, at the time,” Jem continues, “and needed to find somewhere else to move to. I got on a bus to Euston and walked to Burton Street to have a look. It was a terraced cul-de-sac of squats and short-life housing, not many people about. There was one guy propping up the railings near 32, looking at me slightly quizzically, a mixture of curiosity and mild threat, an interesting looking young gentleman. That was the first time I met Shane and as time went by, we became friends in the way one seemed to in that community, by degrees through living as neighbours, going to the same pubs etc...

“Shanne Bradley lived in number 32,” he recalls. “I can’t remember who else was there when I first moved in. James Fearnley moved in at some point, after he’d passed his audition for The Nips and eventually Shane ended up living there too, in the room next to mine.

The Nips, with Shanne Bradley (centre)

“It seemed like every other person played in some band or another, rehearsing in basements. I didn’t play music then. At some point Matt Jacobson, the bass-player in the Millwall Chainsaws, had a good laugh when I said to him, ‘I’d love to be able to play guitar’. He seemed to think it was hilarious that anyone couldn’t and asked Matt Ducasse, who played guitar in the Russians, to write me out some chords. I got hold of a cheap guitar and started learning.”

Jem vividly depicts the first time he played with Shane.

“Cathy Cinnamon lived in Number 32,” he recalls. “She was a teacher and she wrote songs and played guitar. The first time I played with Shane was with Ollie Watts (the Chainsaws drummer), in a band formed to record some of her songs. I think Shane played bass. We rehearsed a bit and went to a studio near Gray’s Inn Buildings. We ended up recording a couple of songs and then digressed into recording some music of our own invention – a reggae version of ‘Banbury Cross’ and an industrial-funk jam.

“Living in London, music was everywhere,” Jem adds. “Reggae, dub, jazz, country, rockabilly, Turkish, Greek and Spanish music, Northern Soul, Irish music, punk, new wave, free improvisation etc. etc. – in restaurants and bars, pubs and clubs, concert halls and on street corners, in movies and on jukeboxes. It was hard to get away from, and all of it found its way into our music at some point in time.”

He’s digging deep now.

“The most important and seminal thing for me though,” he ruminates, “in the immediate musical culture around me, was the permission to play music, to disregard its rules and conventions, to play it badly, but seriously, while learning, rather than wait to become a virtuoso, something that was never going to happen. And now 40 years later, still has not.”

In the spring of 1981, The Millwall Chainsaws renamed themselves The New Republicans and included Shane MacGowan in their line-up. They only ever played one gig – a five-song set of Irish ballads and rebel songs at Richard Strange’s Cabaret Futura.

“We were thinking of it as a one-off,” MacGowan later reflected to Ann Scanlon. “But we quickly realised that if it caused that many people to be upset, or to wonder what the fuck was going on, then it was worth continuing with.”

Jem takes up the story.

“Shane asked me to play guitar in whatever was to be the next incarnation of The New Republicans. It took a while to get going with that – we’d make a plan to meet up to go through some songs and something would get in the way. The procrastination was almost endless. And then sometimes it worked and we’d spend a few hours in Shane’s flat. He’d play a song on guitar and I’d try and work out a part on mine. Increasingly, there was an idea to try and make my parts sound like a banjo, some kind of driving, fast picking, as opposed to strumming, which eventually led to the brilliant realisation that getting hold of an actual banjo might be a good idea.”

The New Republicans never did get around to playing another gig; rather, the first public appearances by Jem and Shane were outdoors.

“Another thing we realised,” Jem explains, “was that rather than sit around in the flat we might as well try and earn some money while we practised by going busking. So, we started going down to Tottenham Court Road tube station, or Finsbury Park, and playing for an hour or two.”

I ask Jem about writing songs with Shane during that period.

“Some songs were pretty much fully formed,” he explains. “Shane had all the parts worked out. With ‘Streams Of Whiskey’, for example, there was the instrumental tune, the verses, the chorus. But with other songs, like ‘Boys From The County Hell’ and ‘Dark Streets Of London’, there was no arrangement save for verses and a chorus.

“I’d improvise a tune while Shane played through the chords,” he says, “and eventually a melody would emerge that we both liked, and that became part of the song. I didn’t think of it as writing at the time – it just gradually dawned on me that it was. And then I took it more seriously – it was another thing I’d never thought I could do, and I began writing by myself, at that time instrumentals, which I’d take along to our sessions.

“I remember with ‘Boys From The County Hell’ thinking there was something spaghetti western about it,” he says. “The long E minor chord, the story, so we worked out the intro in that vein. Shane was strumming the E minor while I picked out the notes. ‘Dark Streets’ was more of a response to the existing melody, looking for something that fitted the chords and the feel of the song, rather than taking the more kind of genre-inspired approach we had to ‘Boys From The County Hell’.”

’82 The Birth of The Pogues

Jem and Shane decided that they needed an accordion player. Once again in true punk style, they recruited who they knew.

“Shane and I spent a while looking for a mythical woman who played accordion,” Jem recalls. “He was convinced she lived somewhere on the Hillview estate, but we couldn’t find her. Funnily enough, I now know exactly who Shane meant! But at the time, the best we could do was find a battered old, small accordion to borrow.”

Step in ex-Nips’ guitarist James Fearnley.

“We remembered,” Jem confides, “that James used to sometimes play the piano if he came across one in a bar or backstage at a Nips gig, and figured that maybe he could learn the accordion. At that time, following our eviction from Burton Street, he’d ended up living in a flat in Mornington Crescent. We knew the block but not the flat number.

“Ever since he first moved into Burton Street, I knew you could always tell where James was by following the sound of a typewriter. He was forever tapping away writing his diaries and novels. I took the accordion to the block, went in the door, walked up and down the ground floor corridor, no sound of a typewriter... eventually though, maybe on the third or fourth floor I heard it, and found the door from behind which it came, knocked, and there was James. It was a bit like handing someone a summons. I said hello, smiled at him and put the accordion in his hand before he could resist. From that point on, he couldn’t say no.

“Shane and I sat around with James and taught him the songs. We made him a cassette actually, so he could learn his new instrument and practise by himself in his flat. Later when Cáit, John Hasler and Spider came along, we’d rehearse in my flat in Hillview. I can’t remember why we moved to Kathy McMillan’s flat, but I do recall that’s where we worked out Pogue Beat, reducing the drum-kit to a floor tom and snare; boom chk boom chk boom chk boom chk... or boom chk chk boom chk chk boom chk chk... a kind of thumping minimalism.”

With Ann, I take the short walk from Burton Street to the site of Pogue Mahone’s debut gig on 4 October, 1982 at The Pindar of Wakefield (now The Water Rats). Ann points down the road at Scala nightclub, the former cinema on Pentonville Road, telling me that Shane went there nightly when Once Upon A Time In America was showing. A few days before their debut show, Shane drafted in Spider to share the vocals with him. John Hasler completed the quintet on drums.

Jem recalls getting to the gig. “It was five minutes down the road. We walked there, carrying our instruments. That much I know. I can’t remember much about it. Seemed to go quite well! I imagine people were surprised – it was maybe not what they were expecting.”

Cáit O’Riordan was brought in on bass in time for The Pogues’ second gig at the 101 Club, Clapham on 23 October, supporting psychobilly outfit King Kurt. In March 1983, Andrew Ranken replaced John Hasler on drums, thus completing the original classic Pogues line-up. They gigged in venues across North London – The Hope and Anchor in Islington; The Bull and Gate in Kentish Town; The 100 Club in Oxford Street; the Sir George Robey in Finsbury Park; The Lady Owen Arms on Goswell Road in Islington; Molly Malone’s and the Auld Shillelagh in Stoke Newington.

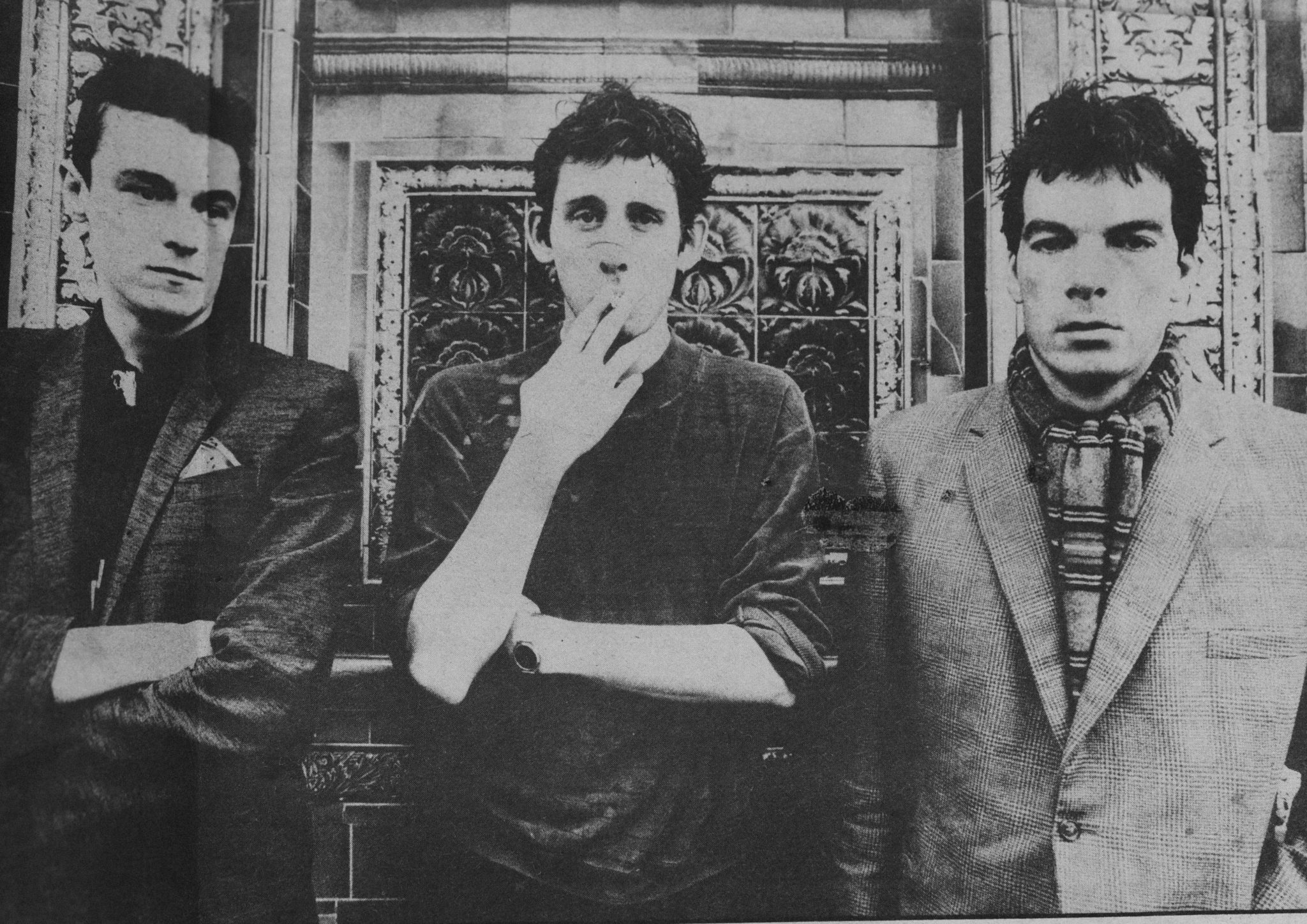

1980. Shane MacGowan with James Fearnley (left) and Andrew Ranken (right)

A representative setlist would have included most or all of these Pogues classics: ‘Streams Of Whiskey’/ ‘Dark Streets Of London’ / ‘Boys From The County Hell’ / ‘Down In The Ground Where The Dead Men Go’ / ‘Poor Paddy’ / ‘Transmetropolitan’ / ’The Battle Of Brisbane’/ ’Repeal Of The Licensing Laws’/ ‘The Auld Triangle’ / ‘Muirshin Durkin’ / ‘And The Band Played Waltzing Matilda’ / ‘Greenland Whale Fisheries’and ‘Dingle Regatta’. It was Irish music alright, for the most part, but with a difference.

They returned regularly to the Pindar of Wakefield to play at a weekly club run by latter-day Pogue Darryl Hunt and Fiona Muray, called Haywire. Other bands on the Haywire bill included The Shillelagh Sisters, Boothill Foot Tappers, the Blubbery Hellbellies, the Skiff Skats and Shanne Bradley’s The Men They Couldn’t Hang.

Trish O’Flynn recalls the make-up of the audience at those Pogue Mahone gigs.

“Initially, it was a mixture of Irish-born, second generation Irish and a few English who appreciated the energy and the vibe,” she says. “And as time went on, the second generation numbers increased. At The Pindar Wakefield, you might have had 60 people on a good night; The Hope and Anchor I think had a capacity of 100. So, they were very small venues but packed. There was a real sense among the second generation Irish that, ‘This is ours’, it’s not ‘Four Roads To Glenamaddy’ or ‘Four Green Fields’.”

’84: Dark Streets of London

Ann and I hop on the tube to Camden town, finishing our tour in The Devonshire Arms, a one-time Pogues HQ, before they moved around the corner to The Good Mixer.

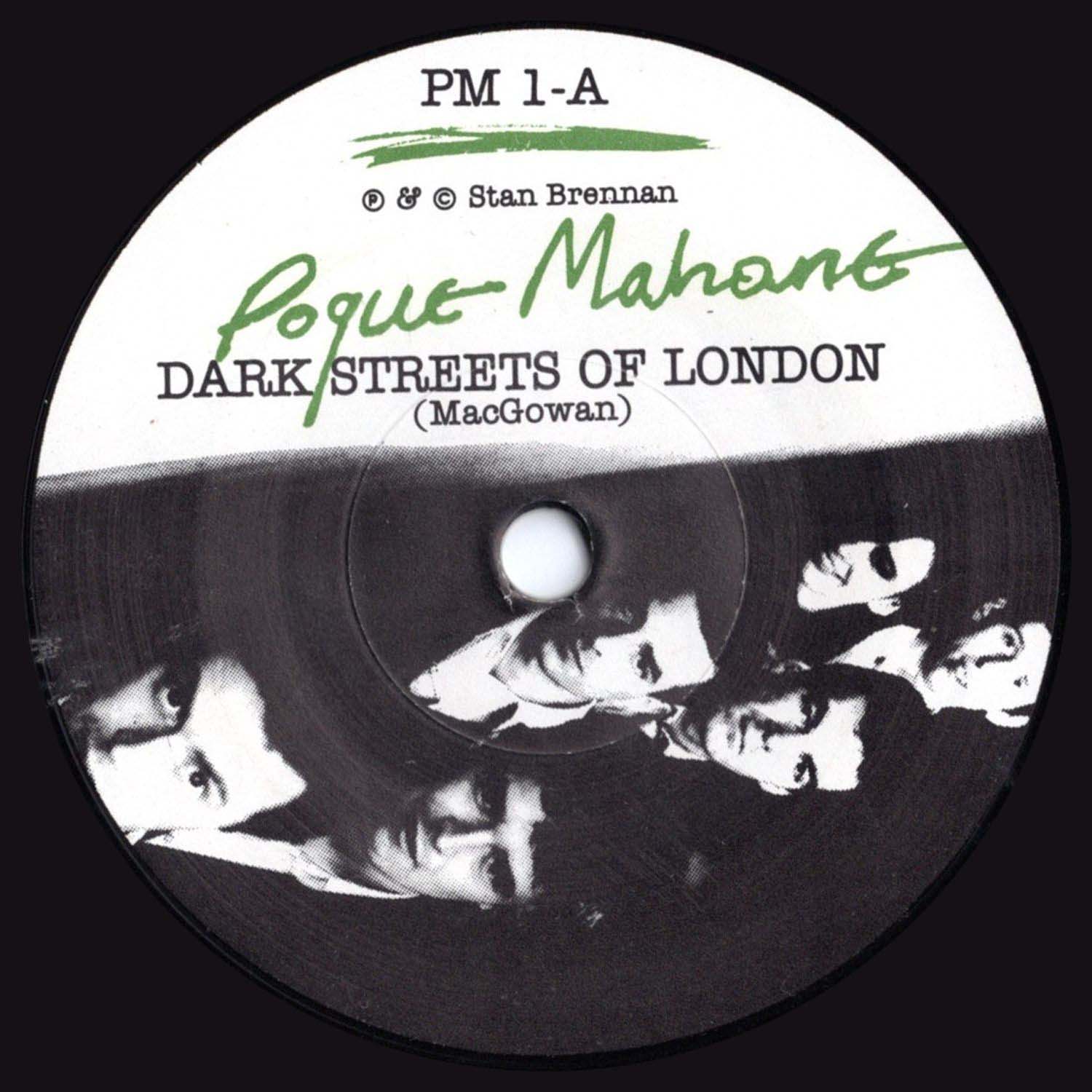

Stan Brennan offered to release The Pogues’ debut single. In January 1984, the band recorded ‘Dark Streets Of London’, at Elephant Studios, Wapping with Stan in the production chair, mixed by Nick Robbins. That was all of 40 years ago in January 1984.

“We got to know the studio well over the years,” Jem says. “But at that point, I’d never been in a proper recording studio. It was all interesting and exciting and new, save for the banjo. Nick Robbins came in with what I now know was a channel strip, raving about its amazing EQ – I was wondering what was he on about? My banjo was deemed not to be of a suitable quality for recording and a ‘better’ one was hired which was really hard to play. It had a wider neck and much heavier strings. So recording was a struggle.”

MacGowan’s marvellous singing of innocence lost forever in London was released on the Pogue Mahone label (PM 1-AA), with an initial pressing of 234 white labels, which were sold at the Irish Centre in Camden Town on 16 March, 1984 – the first place Pogues records were ever purchased.

John Peel and Kid Jensen gave the track some airplay, but record labels weren’t biting – except that is, for Stiff Records. Founder and label boss Dave Robinson remembers his first sighting of the gang.

“I heard of this band, Pogue Mahone, and thought I gotta go and see them,” he says. “Shane was always good value for money. So, I went down to King’s Cross – it wasn’t exactly jammed, but it was a good crowd. And they did three fast – very fast! – numbers. I was just getting the first pint and then they fell off the stage and disappeared. So only the drummer was left – he had one snare drum and the bass drum.

“I went into the public bar, and they were all there having a drink and laughing. And so, I thought, ‘Yeah, why not?’ So, the first thing I said was, ‘You can’t allow Pogue Mahone, I’m not interested in Pogue Mahone. I think it’s very funny and it’ll be good in the press down the road, but what about The Pogues?’”

A deal was struck, initially for the re-release of ‘Dark Streets Of London’ and then later for the album that would become Red Roses For Me – but hey, that’s another story…

The Pogues in the mid-80s

December 23: Tipperary

At the end of Shane’s Requiem Mass, the congregation left the church to the strains of ‘Mo Ghile Mear’ and we made the short journey to Noreen Cavanagh’s public house, The Thatched Cottage in Ballycommon, close to the MacGowan’s old farm cottage in Carney Commons in rural north Tipperary, for what proved to be one hell of a wake.

Johnny and Mick Cronin, Fiachra Milner and Brian Murphy from MacGowan’s last band, Cronin, backed by Colm Mac Con Iomaire, Sharon Shannon and one-time Pope, Andy Nolan, played for hours, through a fair puck of Shane’s songbook, including ‘If I Should Fall From Grace With God’, ‘Sally MacLennane’, ‘Victoria’ and ‘The Broad Majestic Shannon’.

Shanne Bradley herself joined them for ‘Gabrielle’; Mundy leapt up with them for the euphoric heights of ‘Summer In Siam’; Glen Hansard was aboard for ‘Bottle Of Smoke’ and ‘Fairytale Of New York’; Lisa O’Neill marvellously appeared for ‘Lullaby Of London’; Kae Tempest rocked the joint with ‘A Rainy Night In Soho’; Niall McNamee jumped up for ‘Thousands Are Sailing’; Camille O’Sullivan delivered an incredible version of ‘The Song With No Name’; Imelda May recited Behan; George Murphy boomed out ‘Dirty Old Town’; The Doran Brothers blasted off with ‘The Rocky Road To Dublin’; BP Fallon sang his version of ‘Gloria’; MacGowan’s close friend Tom Creagh delivered a fantastic rendition of ‘Ballingarry’; and local Tipp man James McGrath played on ‘White City’.

Wonderfully, Spider Stacy joined the band on stage for ‘The Sick Bed Of Cuchulainn’, ‘Poor Paddy’ and ‘Boys From The County Hell’. They are songs that will be sung in one hundred years’ time and in among them, sounding as fresh as a daisy, was The Pogues’ immortal debut single ‘Dark Streets Of London’.

“I’m buggered to damnation and I haven’t got a penny,” Shane MacGowan would sing, “To wander the dark streets of London.”

Even then, he knew.

RELATED

- Opinion

- 16 Dec 25

The Irish language's rising profile: More than the cúpla focal?

- Opinion

- 13 Dec 25