- Opinion

- 28 Dec 22

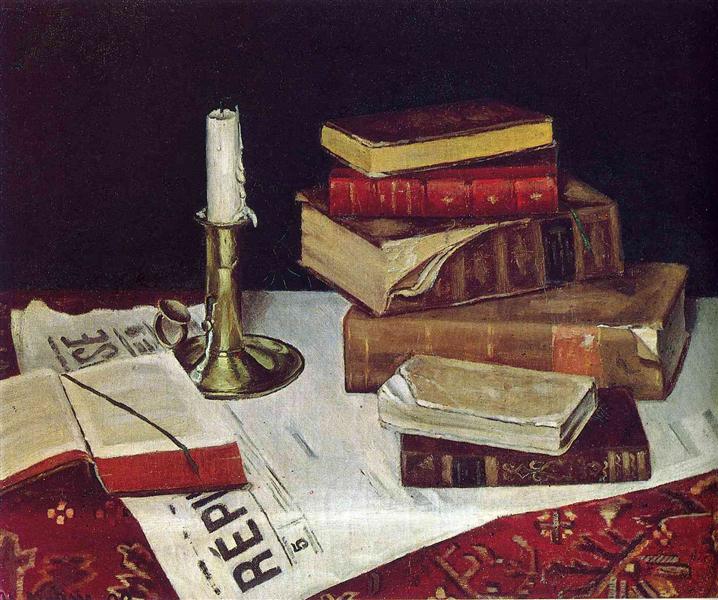

Pat Carty puts down his pocket Dostoevsky, lights a pipe, and selects several books that tickled his fancy in 2022.

“A reader lives a thousand lives before he dies,” George R.R. Martin once said. “The man who never reads lives only one.” Wise words indeed, and the last twelve months have offered us all ample opportunity for such between the covers. Here, in no particular order or preference, are just some of the books of 2022.

Irish Fiction

Trespasses – Louise Kennedy (Bloomsbury)

Delivering on the promise that roared out of her short story collection, The End Of The World Is A Cul De Sac, Kennedy’s debut novel tells the love story of Cushla, a catholic primary school teacher, and Michael, a protestant solicitor, in 1970s Belfast. The era is perfectly evoked – Johnny Giles is playing for Leeds, Chinatown is in the cinema, and Cockney Rebel are on the radio – and Kennedy’s characters get on with everyday life despite the constant shadow of The Troubles which has even small children employing the terminology of terrorism. People are stopped by soldiers, Cushla knows to scrub the ash Wednesday evidence from her forehead, and a weekend in Dublin with no security forces on Grafton Street is a relief but it’s the human story at its centre that shines out from this beautiful piece of work.

Review

The Amusements – Aingeala Flannery (Penguin Sandycove)

Another debut, Flannery’s episodic look around her beloved Tramore mainly concerns two friends separated by economic circumstance. Stella’s allowed to go out into the world while Helen's hopes are dashed, chained as she is to her hometown, which is as much a main character as anyone else. The supporting cast is equally well-drawn with Flannery skilfully wrong-footing the reader when it comes to Stella’s mother. She seems horrible, then you’re forced to reconsider, before her actions confirm that she’s a despicable auld yoke. Flannery then casually goes all Joycean when the butcher takes a walk around the town. Marvellous.

The Deadwood Encore – Kathleen Murray (Harper Collins Ireland)

Laugh out loud funny novel about Frank, a seventh son of a seventh son for whom the healing touch is proving elusive, and a brother about to make a life choice that will throw the numbers off anyway. He takes his deceased father, who has returned to this plane in the form of a wooden statue – stay with us – on a road trip in order to uncover the late pater’s past. Murray’s ear for dialogue is unerring; look out for Frank’s inner monologue concerning the problems of eyeing up a potential mate who is expected to deliver the required number of offspring.

Advertisement

The Singularities – John Banville (Alfred A. Knopf)

Brilliantly layered final - according to the man himself – ‘serious’ novel from the author who should have won the Nobel a few times at this stage. Characters return from pervious works into a world that is folding in on itself thanks to the theories of Adam Godley, Sr. which show that this universe is being rent apart by its uncovering, just as Banville is pulling down the shutters on the dimension he’s created, compressing it all down to a glorious final full stop.

Review

The Raptures - Jan Carson (Doubleday)

Antrim’s mistress of magical realism came out of the traps early in 2022 with her best work yet. A mystery illness starts to claim the lives of school children in 1980’s Ballylack, allowing Carson to paint a remarkable picture of both grief, as some families are devastated, and relief as others are spared. Her shots at religious extremism all hit the bullseye but it’s the manner in which she elicits sympathy for characters where you wouldn’t expect it, like narrator Hannah’s father or the bigoted but naïve Alan, and small acts of bravery from Hannah’s mother, that really impress.

Review

Bonus Round: Five entries are just not enough to cover all the great Irish fiction from 2022 so we’re going to borrow a few chairs from the international section and crow about a few more of our own.

Spies In Canaan - David Park (Bloomsbury)

Taking a break from the usual setting of his native Northern Ireland, Park’s astoundingly great novel, which bares comparison with the Steinbecks and Hemingways he mentions in passing, flashes back from today to the last days of the Vietnam war. Michael Miller is dragged back to his past, a place that can “pull you in like quicksand, drag you down until you go under,” where he worked with ruthless senior CIA analyst, Ignatius Donovan, a man who knows the war is lost and the best that can be hoped for is to get out in one piece. Saigon falls, people are left behind, and, years later, questions must be answered.

Review

The Marriage Portrait - Maggie O’Farrell (Tinder Press)

Remember when O’Farrell broke your heart with the story of Shakespeare’s son and the grief of Anne Hathaway in Hamnet? Well, that was no fluke. Taking a painting by Agnolo Bronzino and Robert Browning’s My Last Duchess as jumping off points, The Marriage Portrait charts the destruction of a free-spirited woman forcibly tethered by marriage in language rich with its own poetry – the descriptions of the wedding ceremony and a caged tiger warrant awards on their own - which further bestows immortality on Lucrezia de’ Medici.

Review

International Fiction

City On Fire - Don Winslow (Harper Collins)

The bad news first. Winslow announced he’s retiring from writing to concentrate his efforts elsewhere. The good news is that City On Fire is the first part of an already-written trilogy, and if the concluding parts are even half as good, we’re laughing. A treatment for the best gangster film you’ve never seen where the uneasy peace in eighties Rhode Island is shattered by loose-cannon Liam and Danny Ryan is forced to step up to protect what’s his as the Italians go all out to drive the Irish Murphia into the sea. The dialogue, the characters and the set-pieces are uniformly superb and Winslow even quotes from Homer and Virgil in his epigrams to show how serious he is.

Review

Advertisement

The Passenger - Cormac McCarthy (Picador)

You wait sixteen years for a new McCarthy novel and then two show up. The master has been working on The Passenger since the 1970s and a character doesn’t come more McCarthy than Bobby Western who’s working as a salvage diver but used to race cars in Europe. He’s sent to investigate a plane crash but one of the passengers is missing. Soon enough, government agents are on his trail. That’s only part of it of course, there’s also room for quantum theory as Western’s father was a physicist who was in at the start of the whole atom-splitting business, Vietnam stories, the real reason Kennedy was shot and, most of all, grief over beloved, deceased sister Alicia, a beautiful genius who takes over for the second novel, Stella Maris. Western goes on a road trip on a two lane blacktop paved with poetry to outrun his pursuers, confront his grief, and contemplate “the abyss of the past into which the world is falling.”

The Candy House - Jennifer Egan (Corsair)

A follow-up – or ‘sibling’ novel, according to her publishers - to Egan’s 2010 Pulitzer Prize-winning A Visit From The Goon Squad, in that characters reappear and it’s written within the same episodic structure, with further stylistic flourishes like a chapter of tweets and one of emails and texts. In an imagined future that’s not very hard to imagine at all a software platform called ‘Own Your Unconsciousness’ allows all our memories to be uploaded cloudwards so past events can be viewed from the perspective of all present at the time. Egan, as she told this very magazine, is “interested in the relationship between data and the human experience” and The Candy House is both an rumination on the human need for connection and a paean to fiction itself, the art form that already “lets us roam with absolute freedom through the human collective.”

Music

This Woman’s Work: Essays On Music – edited by Sinéad Gleeson and Kim Gordon (White Rabbit)

Hard to pick a highlight from this collection of essays but co-editor Sinéad Gleeson’s examination of the fascinating life and career of electro-pioneer Wendy Carlos would be up there as would Anne Enright being tongue tied in the presence of Laurie Anderson. If I have to pick just one, I’ll go for Leslie Jamison’s ‘Double-Digit Jukebox: An Essay In Eight Mixes’ which proves that the best music writing is as much about the listener as it is about the art itself. According to the press release, the book was "published to challenge the historic narrative of music and music writing being written by men, for men." No arguing with that but what’s really important is that it’s all great.

Review

Themes For Great Cities: A New History Of Simple Minds – Graeme Thomson (Constable)

Perhaps when you think of the words ‘Simple’ and ‘Minds’ at the same time, you only picture doves and Belfast Children and endless ‘Ooh, Ooh, Ooh’ refrains – and what the hell is wrong with any of that – but there is another version of the ‘Minds, the Eurocentric dance/rock band who peaked with 1982 masterpiece New Gold Dream and it’s this version that Thomson documents, brilliantly. It’s the story of the friendship between Charlie and Jim, two Glaswegians who travel across Europe reading Camus and listening to Chic and Kraftwerk and then distil it all down to “artful trance-rock buoyed by warm, hummable hooks.” He also points out, quite correctly, how much of U2’s post-War rethink came from listening to these great Scots with The Unforgettable Fire “profoundly in thrall to its [New Gold Dream] fuzzy ambience”.

Review

The Philosophy Of Modern Song – Bob Dylan (Simon & Schuster)

Yes, he could have included a few more women and some actual ‘modern’ songs but The Hibbing Hipster uses the work of everyone from Bing Crosby to The Clash as leaping off points to free associate about everything from New Orleans voodoo to his ‘solution’ for divorce. He does drop the odd clue about himself, such as a possible reason why he’s still on the road when he’s talking about Willie Nelson or perhaps explaining the need to change his name while listening to Johnny Paycheck but this is more akin to calling around to Dylan’s house for a jar while he spins a few records and rattles on about them, and who wouldn’t want to spend an evening like that? Don’t bother with the ‘signed’ copies, mind.

Review

Surrender: 40 Songs, One Story – Bono (Hutchinson Heinemann)

You might have missed it but Bono put a book out this year. It’ll hardly comes a major revelation to learn that the human dynamo knows how to spin a yarn and weave a tale, although it probably helps if you’ve had a life as full of incident as his. Taking us all the way from Boy to Man, Surrender has the remarkable supporting cast you might expect – everyone from Guggi to Gorbachev – including his late father who looms large, and it's reassuring for the rest of us to learn that even yer man out of U2 still longs for affirmation from the Da. Bono also heaps praise on his bandmates at every turn and has anyone ever loved their partner as much as this fella? The Ali Hewson in these pages proves the old saying; out in front of every good man is an even better woman showing him how it’s done.

Advertisement

Carty's House, yesterday.

Carty's House, yesterday.The Islander: My Life In Music and Beyond - Chris Blackwell with Paul Morley (Nine Eight Books)

If, like me, you count Island records as one of the greatest labels of them all then Blackwell’s book is an absolute joy. He’s one of those old school gents who was born into enviable circumstance; Ian Fleming and Errol Flynn were family friends growing up in Jamaica with Flynn being ‘especially fond’ of Blackwell’s mother. Blackwell worked on the production of Dr. No and then moved into music through stocking jukeboxes and then supplying precious wax to the island’s growing sound system scene before heading for Britain to sell his wares. The Island years feature a cast of characters that’s scarcely believable – Roxy Music, Nick Drake, John Martyn, Toots Hibbert, Grace Jones, Tom Waits, and that’s not to mention Bob Marley or U2. Blackwell’s preference for the outsider artists marks him out for others in his position and his love for Jamaica would nearly bring a lump to your throat. Just try to imagine the last fifty-odd years of music without him. The audiobook, read by a perfect Bill Nighy, is also highly recommended.

Editor's Choice

The Road To Riverdance - Bill Whelan (Lilliput)

In a career that began in the 1960s, Bill Whelan has worked as a composer, producer and arranger with some the biggest names in Irish and international music, including Kate Bush, Van Morrison and U2, as well as Irish Eurovision winners like Johnny Logan. Over the years, there have been extraordinary highs – culminating in the global success of Riverdance. But it all began in post-war Limerick, a time and a place which is brilliantly evoked in The Road to Riverdance. The book is written with unflinching honesty – including his battles with the demon alcohol – and often wry, self deprecating humour. It paints an unforgettable picture of how one man navigated the rapids of music in Ireland – and came up trumps in the long run. Along with Paul Brady's Crazy Dreams, it's an essential read for anyone who loves Irish music.

Advertisement

International Nonfiction

Rogues: True Stories of Grifters, Killers, Rebels, and Crooks - Patrick Radden Keefe (Picador)

A greatest hits collection from on one of the world’s best journalists’ tenure at the New Yorker. He’s so good, in fact, that even when he runs risk of falling foul of El Chapo – which would probably result in something more stinging than a mean tweet – by revealing his Viagra use in ‘The Hunt For El Chapo’, the drug lord actually asks Radden Keefe to write his memoirs. Fearing a scenario where the writer “does not necessarily survive Act III”, he wisely demurs. That’s not even the best article here. What about Mark Burnett, the man who gave us Donald Trump, or Hervé Falciani versus the Swiss banking system, or the total bullshit of the high-end wine market? According to the preface, the younger Radden Keefe reckoned that “where nonfiction was concerned, a big magazine article might be the most glorious form.” Rogues argues his case very convincingly.

Review

Colditz: Prisoners Of The Castle – Ben Macintyre (Penguin Viking)

I grew up on a diet of Sunday afternoon war movies so I already knew of the titular castle on the hill, deep in Nazi Saxony. This last stop for prisoners with a history of escape attempts was all stiff upper lip, daring-do, and Fritz being outwitted, right? Well, that’s part of it but thanks to his usual exemplary research, Macintyre illuminates the dark corners of das Schloss with class conflict, treachery and even Gerry’s personality getting a look in. There’s still plenty of action, mind, with various tunnels, disguises and forged papers worked up on cobbled together typewriters using photographs taken on cameras fashioned from cigar boxes. While not afraid to show the tedium of captivity either – have you ever been bored enough to parachute a mouse out the window? - this really is thrilling history. If public transport was as reliable as Macintyre, you’d never be late for work again.

Burning Questions - Margaret Atwood (Chatto & Windus)

If you, as I, thought the only way to get away from a gaggle of crocodiles was to run across the top of their heads à la Roger Moore’s Bond in Live And Let Die then prepare to have your world turned utterly upside down. The wiser approach, according to double Booker-winner Atwood, is move in zigzag patterns as crocodiles have problems with corners. This is but one of the pearls on offer in her latest essay collection, although heavier fare is tackled in the form of Trump, #MeToo, Obama, 9/11 and all the other subjects you might expect from the last twenty-odd years. She also offers appraisals of fellow authors like Alice Munro and L.M. Montgomery, a piece about The Handmaid’s Tale making it on to the telly, and the passing of her long-term partner, Graeme Gibson, in 2019. She’s good company no matter what topic she lands on.

Happy-Go-Lucky - David Sedaris (Little, Brown)

Long-time fans of Sedaris, one of the funniest writers in the world, will already know of the ‘troubled’ relationship he had with his father, a seemingly thoroughly unpleasant fellow called Lou. Sedaris the younger got his own back by making money out of writing about their conflict and “better yet was the roar of live audiences as they laughed at how petty and arrogant he was.” Sedaris Senior passed away last year at the ripe, old age of ninety-eight and more than a quarter of the essays here concern his final days. Naturally, these are more serious than we might be used to but he still has the craic elsewhere at the gentle expense of his partner, Hugh Hamrick. Lockdown meant they were together more than was probably good for them but at least they’ve discovered that “sleeping is the new having sex”. I could have told him that years ago.

The Extraordinary Life Of An Ordinary Man: A Memoir - Paul Newman (Century)

An unusual memoir in that Newman was that rare star who never bought into his own myth. In fact, he likely didn’t want this published at all, having sat for a series of interviews with his pal Stewart Stern during the eighties only to then burn the tapes. Thanks to surviving transcripts we meet a man who reckoned he owed it all to ‘Newman’s luck’. He was certainly fortunate to have been blessed with the face of Apollo but he’s too hard on himself and his acting talent, as anyone who’s ever watched anything from Hud to Road To Perdition can attest. He’s also honestly critical about his first marriage, the death of his son, and his famous – and highly laudable – charity work, reckoning it was easy for him to give because he had plenty. While it’s always good to hear that immortals are just as messed up as the rest of us, you’ll come way from this admiring Newman even more.

Advertisement

Irish Non Fiction

Negative Space – Cristín Leach (Merrion Press)

Leach is, with apologies to all others ploughing a similar furrow, the leading Irish fine art critic. She knows her onions, especially if said onions have been painted as a still life or hewn from clay or plaster. No surprise then that this memoir is a work of art in and of itself. “Writing about art,” she quite rightly argues “must be personal and objective” and it’s in the gaps between what is said and unsaid that “writing comes alive.” The writing in this series of overlapping essays with little heed for linear structure really does come alive as Leech is having reviews published at an impossibly early age one minute and dealing with betrayal the next. Negative Space is both a howl of pain at a life derailed and a celebration of the power of the written word and art as bulwarks against ill fortune.

A Guest At The Feast - Colm Tóibín (Viking)

Tóibín could probably write a manual for a gas boiler and still make it gripping. Here, he gets his teeth into a couple of popes, the work of John McGahern, and light and shade in art, but he’s even better when he turns the focus on himself. He takes us through his own cancer experience – don’t call what all started with his balls a battle - and transports us back to the Enniscorthy of his youth and the excitement of the Fleadh Cheoil, and then his mother becomes the kind of reader every author dreams about. His piece about Francis Stuart, the Irish writer who decided to take a post in Berlin in 1940 and ended up broadcasting back to Ireland from Nazi Germany, is worth the cover charge all on its own.

The Written World - Kevin Power (Lilliput Press)

Power is another fella who would sicken anyone. Reviewing books at the same time as him is a very frustrating business because he’s so bloody good at it. He’s also written some decent novels too, which only further marks him down as a complete bastard. In The Written World he’s expounding on literary theory one minute and putting the boot into the work of Marlon James or William Gibson the next. He can go all high-brow, exposing the debt Martin Amis owes to Oscar Wilde, and then prove he's a man of the people by praising Ross O’Carroll-Kelly and a God-awful/great sport Bill Clinton/James Patterson collaboration. When he quotes Clive James, who knew a review “was not just where culture happened but where art could happen too,” he’s summing up his own admirable approach.

Heiress, Rebel, Vigilante, Bomber: The Extraordinary life of Rose Dugdale - Sean O’Driscoll (Sandycove)

If you could recall the name Rose Dugdale before opening O’Driscoll’s book, you most likely know of her as the Brit toff who was involved with the Russborough art theft of 1974, art that Dugdale and her cronies then threatened to destroy unless IRA prisoners were transferred to Northern Ireland so that they might attain political prisoner status. Dugdale ended up inside herself as a result although her partner Eddie Gallagher tried to get her out with a kidnap plot. O’Driscoll colours in the background of this former debutante who holds an economics PhD and was convinced by a lover that supporting the IRA was the right thing to do. Once she gets out of prison, it’s not long before she’s up to her old tricks again. According to her son, she just liked to rebel.

Fierce Appetites - Elizabeth Boyle (Sandycove)

Boyle, a medieval historian currently clocking in for the Department of Early Irish out in Maynooth, draws on her vast reservoir of ancient knowledge – was Queen Medb created as a warning against giving power to women? – to also tell her own story, and much else besides. She’s a heavy metal fan who had visions of the divine as a child, celebrated her fortieth birthday with a threesome – who didn’t? – and uses hooch to quell the “raging cacophony in her head”. Why wasn’t this person lecturing when I was in St. Patrick’s? From the toppling down of statues as a way to write history to the medieval melting down of murderers, this really has it all, although I don’t agree with her assertion that were he still with us, Cúchulainn would be trying to chop my head off on the internet.

![Minister James Lawless: "How do we have two different rules [for alcohol and marijuana]?" Minister James Lawless: "How do we have two different rules [for alcohol and marijuana]?"](https://img.resized.co/hotpress/eyJkYXRhIjoie1widXJsXCI6XCJodHRwczpcXFwvXFxcL21lZGlhLmhvdHByZXNzLmNvbVxcXC91cGxvYWRzXFxcLzIwMjVcXFwvMDRcXFwvMDMxNzA1NTZcXFwvTWluaXN0ZXItRURVLWJ5LUFSLTI2LmpwZ1wiLFwid2lkdGhcIjpcIjMwOVwiLFwiaGVpZ2h0XCI6XCIyMTBcIixcImRlZmF1bHRcIjpcImh0dHBzOlxcXC9cXFwvd3d3LmhvdHByZXNzLmNvbVxcXC9pXFxcL25vLWltYWdlLnBuZz92PTlcIixcIm9wdGlvbnNcIjp7XCJvdXRwdXRcIjpcImF2aWZcIixcInF1YWxpdHlcIjpcIjU1XCJ9fSIsImhhc2giOiI5Nzg2MDBhOGZkZTdmZjcwMGM3ZDE5MDdkZjhlYmE1MmQ3YjAzZjMwIn0=/minister-edu-by-ar-26.jpg)