- Opinion

- 14 Mar 23

The Whole Hog: Woody Guthrie, Irish Music Month, and the enduring power of three chords and the truth

As Irish Music Month begins, it is worth remembering the power of great songs – and the importance of local radio in the campaign against bigotry and exclusion. Put the two themes together and we would doubtless see some powerful public service radio…

Just over seventy-five years ago, on January 28, 1948, a plane with 32 people on board plummeted to earth at Los Gatos Creek in the Diablo mountain range near Coalinga in California. Everyone on board died.

The plane had been chartered by the US Immigration and Naturalization (they use a ‘z’) Service to ‘repatriate’ – it is a euphemism for the harder word ‘deport’ – guest farm workers and illegal immigrants to Mexico.

The great American songwriter, poet and activist Woody Guthrie was living in New York at the time. He couldn’t help noting that the New York Times, named only four victims in its reportage of the tragedy: the flight crew and the security guard. The rest were described as “deportees”.

This was also the case with many other newspapers and radio stations.

In response, Guthrie penned a powerful, poignant, angry poem, giving the dead symbolic names:

“Goodbye to my Juan, goodbye, Rosalita,

Adios mis amigos, Jesus y Maria, You won’t have your names when you ride the big airplane, All they will call you will be ‘deportees’.”

That first version of the tract is best described as spoken word music, Guthrie chanting it with only very basic accompaniment.

Ten years later, when schoolteacher Martin Hoffman gave it a melody, it assumed the form in which we know it now – the song is called ‘Deportee (Plane Wreck at Los Gatos)’.

Not long afterwards, Woody Guthrie’s friend Pete Seeger started singing it at concerts and festivals. Over the years it has been sung and performed by a wide range of artists, including Guthrie’s son Arlo, Joan Baez, Cisco Houston, Willie Nelson, Dolly Parton, Johnny Cash, Bruce Springsteen and Ani DiFranco.

It’s well known in Ireland and has been interpreted by many, most notably the legendary Kildare folk hero, Christy Moore.

To be fair to California, and Californians, local coverage was much more extensive in the immediate aftermath and the names of the other victims became known. However, it wasn’t until 2013 that a definitive list was published and a memorial unveiled in Fresno.

The tragedy later led to the foundation of the United Farm Workers Union by Cesar Chavez, whose reaction to the tragic crash was that farm workers should be treated “as important human beings and not as agricultural implements.”

The cynicism and disrespect to which those who died were subjected is a central target of Woody Guthrie’s protest:

“They’re flying ‘em back to the Mexican border,” he wrote, “To pay all their money to wade back again.”

And then this: “The sky plane caught fire over Los Gatos Canyon/ A fireball of lightning, and shook all our hills…

“Who are all these friends,” Woody asks, “all scattered like dry leaves? The radio says, ‘They are just deportees’.”

It’s a powerful work that is still ragingly relevant. Woody Guthrie famously inspired Bob Dylan to pick up the guitar in protest – and to write some of the greatest folk songs of the modern era, including ‘Masters of War’, ‘A Hard Rain’s A Gonna Fall’, ‘Hurricane’, ’Maggie’s Farm’ and ‘The Times They Are A Changin’. He also inspired Bob Geldof of The Boomtown Rats, with the Irish band taking their name from Woody’s teenage gang, as described in his autobiography Bound for Glory.

With that debt to Woody writ large, The Boomtown Rats went on to score an impressive sequence of hit records starting with ‘Looking After Number One’ in 1977. The following year, they became the first Irish rock band to have a UK No.1 with ‘Rat Trap’.

They started 1979 with another UK No.1, ‘I Don’t Like Mondays’, which became their first Irish chart topper, as well as becoming a hit in a dozen countries, including Canada, where it helped to turn the band’s third album The Fine Art of Surfacing into a platinum record. The band also hit the US charts for the first time.

And in 1980, they had a global hit and an Irish No.3 with ‘Banana Republic’, a protest song that owed more than a little bit to both Guthrie and Dylan – as well as The Clash and Bob Marley – and delivered a scathing denunciation of a shambolic country run by a venal nexus of corrupt police, politicians and priests.

It makes sense to remember these events during Irish Music Month. The Boomtown Rats achieved all of this success with very little support from Irish radio – because all we had then were RTÉ and pirate stations. So what might they have achieved in they had started out with a network of independent stations to support their work via radio play?

Well, that would depend on whether or not the stations were prepared to embrace Irish music in all its gnarly glory. Which is, of course, what Irish Music Month is all about.

The bottom line is that there is not a single artist who would say other than that having the support of radio locally can make a huge difference, if you are attempting to forge a career in music internationally. Ask Dermot Kennedy. Ask Aimée. Ask CMAT. Ask Róisín O. Ask even a newcomer like Cian Ducrot. Radio play can make all the difference.

TWISTED AND WRONG

Like Bob Geldof with ‘Banana Republic’, Woody Guthrie knew what he was talking about in ‘Deportee’. Migrants in the US don’t steal anyone’s jobs: as elsewhere in the world, including here in Ireland, they largely do the dirty, menial jobs that the middle classes need done but don’t want to do.

They’re drawn northwards by the same need that’s inspired migrants for two centuries and more: that is, by a desire to build a safer, less precarious life and to give their children greater hope than their parents ever gave them.

That wish has grown ever more urgent in parallel with the rise of the related scourges of narco-terrorism, authoritarianism, land-grabbing and eco-vandalism – vices that still prevail in far too many parts of the world, and also seem to be becoming more prevalent.

There’s nothing new in the reality of migration. Around the world over the past two centuries, whether they were fleeing war, persecution or famine, vast numbers have left their homes to pursue the dream of finding a better life and greater freedom to live it.

They left from Europe and Russia to the United States. In the middle of the 19th Century, two million Irish left a country ravaged by famine, most of whom ended up in North America.

From China they spread right across the Pacific basin, including the western States of the US. From Central and South America they headed north, also to the US.

And as old colonial powers exhausted themselves in war after apparently endless war, their depleted human resources were replenished – first, by people from the old colonies and then by those drawn north and west by the prospect of a better, freer, life.

Notwithstanding the fact that they are essential to our economic life and hugely positive contributors to our social and cultural tapestry, migrants everywhere are too often met by ingrained prejudice, exploitation and violence.

Sadly, right now Ireland is no exception, with an increasingly vocal minority expressing hatred and hostility towards people from war-torn places like Syria and Ukraine who land here. Of course it is pathetic. After all, the Irish went everywhere, well, everywhere that spoke English. So, by what twisted logic do some Irish people feel that they have a right to resent migrants coming here?

It makes no sense. It is evil, nasty and wrong. It is also racist. But here’s the thing: given their strong bond with local communities, independent radio stations are uniquely well placed to play a huge part in countering that by demonstrating that – in truth – migrants are no threat whatsoever to local communities.

We might begin by playing ‘Duel Citizenship’ by Denise Chaila. “I am tired of proving that I am as much Denise,” the Limerick Zimbabwean rapper complains, “As I am Mkawa/ So cén scéal?/ Because I learned how to be Irish/ Knowing that some people/ Would always think I was beyond the pale.”

When, of course, it is the haters whose view of the world is twisted and wrong. Local radio can show that to people too, far better than if they heard it on RTÉ.

DOING THE DIRTY WORK

The writer Tash Aw is Malayan and Chinese. He explores migration and identity in his fascinating book Strangers on a Pier. While his focus is on the Chinese experience, his insights are universal.

In Malaya, where he grew up, ethnic Chinese citizens don’t have the legal right to own certain kinds of land, vast tracts of prime forest or real estate.

“Wrong race, wrong religion,” he says, adding that “We didn’t think of ourselves as immigrants – very few immigrants do – but here was a reminder. We could possess the nationality, but we couldn’t fully possess the earth.”

Some so called Irish people want to deny even that nationality to Denise Chaila and others like her. It is a form of prejudice and exclusion that would make a good editorial theme during Irish Music Month. So cén scéal? What’s the story? That’s a question we need to ask, as we listen to the music of the new Irish…

The version of ‘Deportees’ on the official Woodie Guthrie website concludes with questions:

“Is this the best way we can grow our big orchards?

Is this the best way we can grow our good fruit?

To fall like dry leaves to rot on my topsoil

And be called by no name except ‘deportees’?”

It’s as pertinent today as seventy-five years ago, perhaps more so. In the UK, the government persists in its grotesque plan to fly asylum seekers to Rwanda. Here, thugs and bullies gather outside direct provision centres and hotels where asylum seekers are being housed.

Yes, there are differences around the world. It remains true that immigrants are treated a great deal better here in Ireland than in very many other countries.

But it can’t be just a matter of how we behave in this country or in Europe. We can’t allow ourselves to forget that the hard labour of migrants around the world helps to support our lifestyle.

Food production, cheap fashion and sportswear are global industries.

For example, fresh blueberries from Ireland appear in a handful of outlets for only a couple of weeks every year. Otherwise, they come from the US, Chile, Peru, Morocco, South Africa, Poland, or the Netherlands.

Migrants are also critically important in seasonal harvesting and production – for example the grapes for our wines, the hops for our beer, the strawberries that make our summer, the apples that define our Autumns are mostly picked by migrant labour.

Even now, as prices rise, few stop to ask about those who put in the hard graft, who do the dirty work. Nope, our key worry – apparently – is about inflation.

Migrant workers picking cabbage

PUBLIC SERVICE BROADCASTING

Migration is nothing new. Nor its twin sister, emigration. Think of ‘The Fields of Athenry’. Of ‘Botany Bay’. Of ‘The Mountains of Mourne’. Of Barry Moore’s ‘City of Chicago’. Of Damien Dempsey’s ‘Apple of My Eye’. Of ‘In Ár gCroithe Go Deo’ by Fontaines D.C. We know all about it here in Ireland and express it through our music and through our songs.

We are not alone. In ‘Across The Borderline’, Ry Coder, John Hiatt and Jim Dickenson wrote about the terrible disillusionment felt by those who make it across the border from Mexico into the US.

“When you reach the broken promised land,” the chorus runs, “And every dream slips through your hands/ Then you’ll know that it’s/ Too late to change your mind/ ‘Cause you’ve paid the price to come so far/ Just to wind up where you are/ And you’re still just across the borderline.”

Aren’t we all, in a way. But it doesn’t have to be like that.

Looking back at the last 120 years, never mind the previous 1,000, political upheavals, wars and weather disasters have repeatedly displaced many millions of people, perhaps even billions.

Bigotry and violence are age-old problems. Ignorance and fear may be at their root but some people are just nasty.

There have been many other great protest songs over the years. Sadly, disgracefully, autocrats, oligarchs, warlords and criminals will ensure there are many more – and then try to suppress them.

‘Deportee’ shows how a song can capture and channel anger, can call for action and compassion, for respect, care and protection. And last. It’s the enduring power of three chords and the truth.

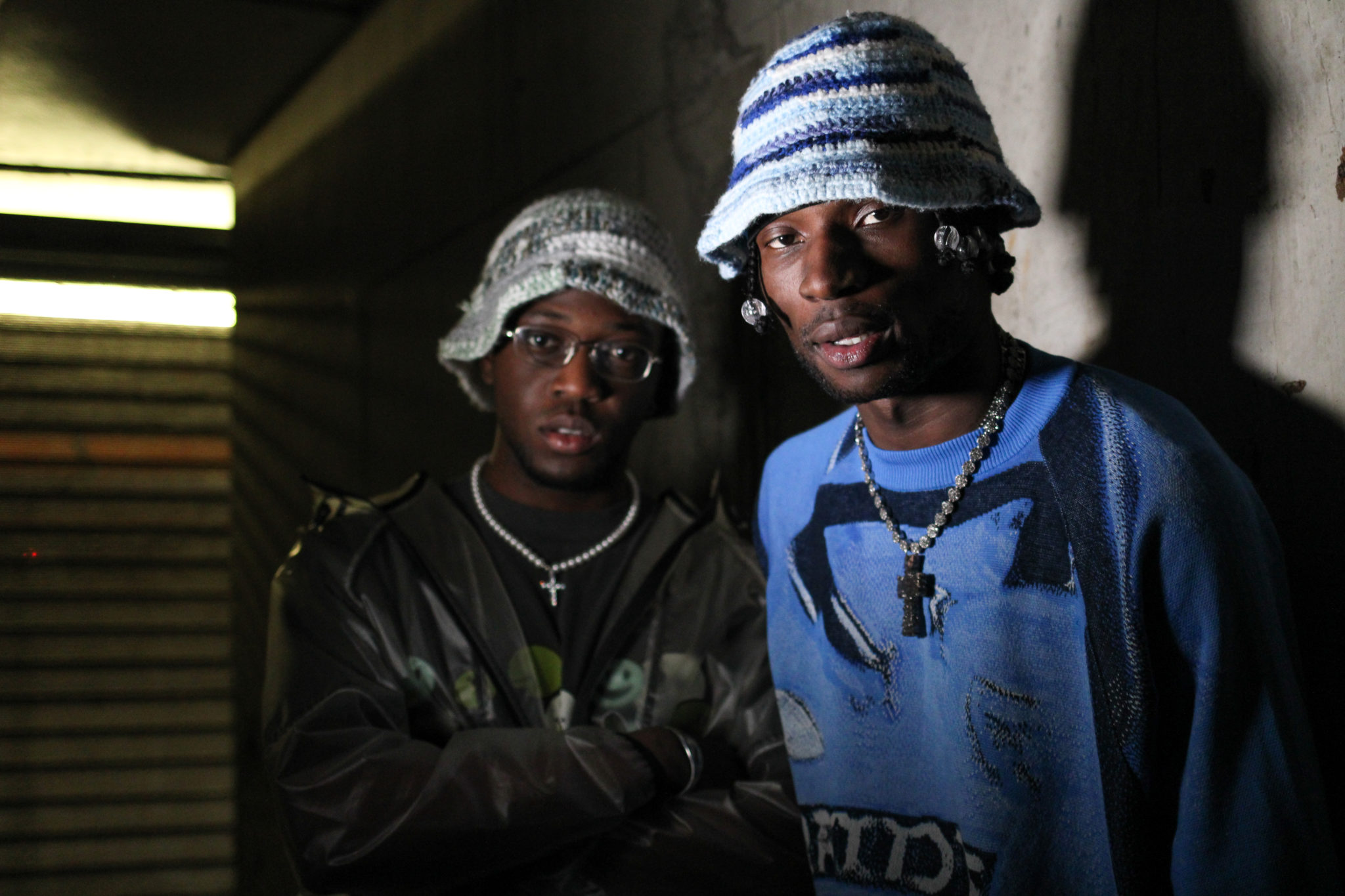

That is something we can celebrate in Irish Music Month. Let Irish independent local radio be a place where those unpleasant and dangerous attitudes to migrants are exposed and shown up for what they are. Let us hear the voices of the new Irish: of Denise Chaila, Tolu Makay, Sello, JyellowL, Celaviedmai, Jess Kav, TraviS & Elzzz, Offica, Loah – and all the rest of the new crew.

Now that would be public service broadcasting at its best.

TraviS and Elzzz. Credit: Abigail Ring

RELATED

- Pics & Vids

- 20 Feb 23

Ireland For All protest in Dublin (Photos)

- Opinion

- 17 Jan 22

Hot Press Top 30 Folk Albums Of The Year 2021

- Opinion

- 22 Nov 19

Album Review: Christy Moore, Magic Nights

- Opinion

- 09 Apr 19