- Opinion

- 06 Jul 23

Trainspotting turns 30: Revisit a classic interview with Irvine Welsh

Irvine Welsh took to Twitter this morning, to mark the 30th anniversary of his iconic debut novel, Trainspotting. "I maybe should say that it seems like yesterday and where has all gone. But no. The truth is it feels ages ago, not just a different era but a different life lived by another person." To celebrate, we're revisiting a classic interview with the Scottish writer...

Originally published in Hot Press in 2002...

Irvine Welsh is full of shit. Or, in keeping with his bawdy vernacular, should that word be ‘shite’? Either way, every time I meet the controversial Scottish author he assures me that his latest book will be his last, that he’s giving up on all this writing bollix and is about to embark on a brand new career as a musician or a superstar DJ or something. Yet, here he is again, the big baldy cunt, sitting smugly (and somewhat drunkenly) in front of my tape recorder at a table in the Octagon Bar, about to tell me all about his seventh novel Porno – the just-published sequel to his mega-selling 1993 debut Trainspotting.

“I say that every time!” he guffaws into his whiskey glass, when I put it to him that he’s published two novels since he last promised me he’d never write another. “I’m worried that I’m gonna say that I will write another book again, and then I won’t – so I’ll stick to that line. I’m never gonna write another book again! I’ve had it!”

Now aged 44, the former TV repairman and clerical temp’s literary output has been a fairly hit and miss affair over the past decade – undoubtedly as a consequence of him spending so much time hanging out with the likes of Primal Scream and Kate Moss – but thankfully Porno is a fast, filthy and furious return to form. In fact, it’s probably the best thing he’s done since Trainspotting, the book which first introduced the reading public (at last count it had sold more than 800,000 copies in 33 languages) to such immoral characters as the conniving Sick Boy, the troubled, drug-addled Spud, the cynical Renton and the truly psychotic Frank Begbie.

Taking up the story ten years on from where Trainspotting ended, the book reunites the old crew in the most unexpected of ways (for one thing, as the title suggests, they’re collectively making a low budget porn movie entitled, em, Seven Rides For Seven Brothers). How does it all work out? Well, the moral of the story, as they should have learnt ten years ago when Renton fucked off with their money, is still that, “Ye cannae trust nae fucker!”

As a central motif, pornography is to Porno what heroin was to Trainspotting. You were a heroin user at one point in your life, but are you a porn consumer?

IRVINE WELSH: I’m not really. You know, it’s like the Nikki character says at the end of the book, I’m not really that into watching other people fucking. Once you’ve shot your duff, when you’re watching pornography, there’s nowhere else to go. The only time I ever really consumed pornography was as a 14-year-old. And then it was almost one of those things where you watched it for education as much as stimulation. You know, just getting your head around how things looked and all of that stuff. But even then, you’d have a wank and then think to yourself, ‘I really should have a girlfriend to do this with’. So the guilt thing was there. And the idea now of sitting down, watching porn and having a wank, and then having that same guilty fucking feeling is absolutely terrifying to me. But it’s also that kind of thing of watching people shagging, there’s an odd detachment that comes into it as well. You’re thinking, ‘I’d rather be involved in this’.

It’s become incredibly mainstream over the last few years…

IW: Aye. And another thing that’s quite distressing about it is that it’s not really about sex – it’s about the performance of sex. It’s become this kind of circus thing – triple penetration, girls taking five fucking dicks, all this stuff. It’s like, how do you get 100 people in a Mini? It becomes more this kind of humiliation, a Schadenfreude kind of thing that creeps into it. And a pornographic sensibility has permeated mainstream culture.

When I wrote about drugs in Trainspotting, the reason it was so powerful, was because it was about an underground culture that was just about to become mainstream. And drugs are fully mainstream now, you know, there’s no drugs subculture anymore. And I think porn is the same now. It’s a pornographic sensibility. Like, it was only legal restrictions on TV that stopped people in Big Brother shagging each other.

And Channel 4 have been showing highly erotic late-night art house stuff for years anyway!

IW: If it’s middle class it’s eroticism, if it’s working class it’s porn. It’s still the same thing though (laughs).

What was it like revisiting the Trainspotting characters?

Ach, it was great – just great fun. It was almost like meeting long-lost friends again. I had a brilliant time doing it. It was weird because it was, like, all these people that I’ve told over the years, ‘No, you’re not these characters,’ and all that… (pauses). Because I spent a lot of time up in Edinburgh, I just started seeing bits of the characters in everybody I was hanging around with. It was a really funny year because just after Glue came out, I was writing Porno, and a couple of pals died up in Edinburgh. Normally when that kind of thing happens – of course it’s been happening over the years, everything’s been going on in Edinburgh, HIV stuff and the gear and all that – but normally when it happens people go all weird and they don’t wanna talk about it. But this time, when it happened, everybody seemed to pull together, which was great.

How did your friends die?

IW: One of the guys had a really bad accident. He was a pal called John Boyle – who the book’s in memorium to (opens book and shows me the dedication) – and he died in a freak accident. Everybody really pulled together. So, in a strange way, I was on a bit of a high when I was writing this.

It’s a very funny book – probably the funniest thing you’ve ever written…

IW: Cheers! That’s great (grins broadly, raises glass of Wild Turkey and clinks it off mine).

Do you think people have to read Trainspotting – or Glue, for that matter – in order to understand the various characters?

IW: Yeah, that’s the thing. I had to read Trainspotting again, because there’s a lot of things in it that I’d forgotten all about. Especially when I’d seen the film so many times, a lot of my sensibilities had been taken over by the film. Like it’s Leslie’s baby that died in the book, whereas in the film it’s Alison’s. There were a lot of things like that, that I kind of fucked up on, in the first draft.

Did you have the movie characters in your head when you wrote it, rather than your own original fictional creations?

IW: Yeah, but not just the movie characters. I had the characters from the stage play as well. I had this Portuguese guy as Spud. Obviously I had Ewan Bremner a bit as Spud, but I also had this Portuguese actor as Spud, because I saw the whole show in Portuguese. Couldn’t understand a word of it but it was the best production of Trainspotting I’ve ever seen (laughs). I had Robert Carlyle as Begbie but I also had this actor called Malcolm Shule, who was the first Begbie who played him in the stage play. He’s a pal of mine, a fucking huge guy. But Robert Carlyle was great as Begbie as well.

The Begbie-narrated chapters were the ones I most looked forward to.

IW: Yeah, they were great fun to write as well. But the funny thing is that I had Ewan Bremner in my head as Renton, as well as Ewan MacGregor. Because Ewan Bremner played Renton in the stage play. So it was just a mash, you know, everything but my own original images of the characters in my head. And then when I started to write it, I found that I was kind of re-appropriating the characters myself again.

Is there talk of a movie adaptation yet?

IW: Yeah. There’s been masses and masses of e-mails building up. I think there’s been about three or four offers already, so I’m just gonna go through them when I get back.

Would you not just go with the original crew?

IW: Well, the original Trainspotting team have got it, and they’re looking at it now. And they’ve got first option on it. But if they don’t want it, there’s loads of people in America who’re looking at it and who’ve made offers for it. I’ve also got my own production company with Robert Carlyle and Antonia Bird. So we’ll see what happens.

You’ve used characters like Rab and Juice Terry from Glue in Porno, and Spud and Renton also made brief cameos in Filth. Why the interaction between novels?

IW: I think it’s that you don’t want to keep inventing characters with the same characteristics each time. When you get a pool it becomes really easy to just kind of throw them into these slots. I think you get a bit lazy. And there’s probably a bit of social responsibility going on there as well. If you’re writing about a small segment of Leith society, you don’t want to portray everybody as a totally fucked-up waster.

You always think to yourself, ‘Well, this is where I come from, all these people, and I’ve got a responsibility not to have everybody viewed negatively’. The more nutters you introduce, it’s almost like you’re creating this monolithic community of nutters, which isn’t really the case.

What’s the reaction of the real nutters in Leith towards you?

IW: Very positive.

Are they reacting to your writing or just to your fame?

IW: I think it’s the writing. I think it’s actually been more negative since the fame. People are negative about the fame, but positive about the writing. When Trainspotting first came out it only sold about 5,000 copies. I think there must’ve been 4,000 of those 5,000 copies circulating in Leith. Everybody was going, ‘Ach, this is great!’ But you sell 5,000 copies or you sell five million copies, it’s still the same book. But people feel something’s been taken away from them. There’s all these translations and it becomes a much bigger thing. Suddenly it’s not ‘our book’ anymore – it becomes somebody else’s film, somebody in London’s film or wherever. And then it becomes Richard Branson’s train advertisements and all that, and it becomes further and further removed. Everybody feels that. I felt it myself. Certainly a lot of the people who were into it at the time felt that. They felt it was another thing being taken away from the working classes – like football and rock & roll and all the other things that were stolen by capitalism.

So now you’re stealing it back?

IW: Yeah. These are my characters, I’m taking them back, this is what they’re doing now – you can speculate all you want but this is actually what’s happened to them (laughs). The lovely thing about it is, this book has had fantastic reviews everywhere. But the only two papers that have been absolutely really, really hostile have been the two Edinburgh papers – The Scotsman and Scotland On Sunday. They’ve been incandescent. It’s been so brilliant the way they’ve reacted. It’s been fantastic. It’s been, ‘Methinks the lady doth protest too much’ type of hostility. The reviews have been terrible. And I love it. I fucking love it!

So you’re not too bothered about what The Scotsman says?

IW: I live in absolute fear and terror of the day that I get a good review in The Scotsman or Scotland On Sunday. It’s real grist to the mill – especially because everybody else has been giving it such great reviews.

You’ve never really had great press in Scotland though, have you?

IW: No – and not just for the writing. I did this thing on the radio about Edinburgh, about how it’s like this fucking museum, and they’ve exiled everybody out to the estates, and the festival’s too expensive, it’s a rip-off – they suck up the arses of tourists and treat all the locals like shite – and just all the usual things that everybody knows about the place. But I said this on national radio and got all these editorials in the Evening News – how dare you do this or say this about Edinburgh?! There was fucking outrage. I mean, you’ve been through all this yourself ...

Yeah, but you’ve got a lot more money than I have, so you can just fuck off on a plane rather than have to stick around to face the music!

IW: Yeah – you’ve gotta hide at home with a fucking baseball bat (laughs). But no matter how much you anticipate the controversy, you still think to yourself, ‘I’m using such broad strokes here to make my point, surely they’re not actually gonna fall for it?’ With that kind of fucking vehemence! But they do! And they come in so fucking nastily.

Is that the reason you mostly live in London?

IW: Ha, ha (laughs). But the thing is, nobody I know reads The Scotsman or Scotland On Sunday. They do read the Evening News, but they read it for the football – the Hibs and Hearts – and the cartoons. The rest of it they don’t pay a blind bit of notice to. So it’s not that kind of thing of people going, ‘The paper says you’re a cunt so we hate you too!’ It isn’t that. It’s more (snorts loudly), ‘The Evening News – fuck that!’ So it’s basically one or two journalists who drink in their own little bar and don’t have much contact with the rest of the city who’re behind it.

It’s not just journalists though. Didn’t a fellow Scottish writer verbally attack you at a literary festival recently?

IW: That was at last year’s Edinburgh festival. There were two of them that went on the attack, I think.

What were their names again?

IW: I can’t even remember myself now (laughs). I don’t think they’ve ever really written anything. It’s usually these academics that’ve written a couple of poems in their spare time, they’ve blagged a grant from the Arts Council to go to fucking Latvia or somewhere, and then they start claiming to represent Scottish writing. That tends to be the kind of mediocrity that the so-called quality literary press in Scotland champion basically.

Is it true that you became a health fanatic for a while?

IW: Nah. What it was was that I had this sort of strange drunken bet that I could run the London Marathon. This was a few years ago, and I just let it ride for ages. And then a friend of mine was diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis, and instead of letting this get her down, she was really quite inspirational, she went on this diet and she’s great now – she’s better than she’s ever been. Her boyfriend as well. They opened this club in Edinburgh and they started this record label up – they just really saw it as an opportunity to get up off their arses and go for it, and do what they’ve always wanted to do. It was just really brilliant watching them. So I figured that this was giving me a chance to try and do something different as well. So I got into training and said I’d run the London Marathon for the MS society. I’ve done it twice now.

I heard that the second time you ran it, you took 40 minutes longer!

IW: Actually it was 45 minutes (laughs). But the first time I ran it, I stopped everything – drink, drugs, caffeine, the lot. And I just really started to get myself together.

That must have been a fair shock to your system…

IW: It did feel strange. I just got so into it. I got into the whole endorphins thing. I was getting high from getting fit and I was really enjoying myself. But afterwards, I vowed never again. Because it’s not a social thing. And you really do miss the social side of things. I noticed that when I was going out, I could stay with people for a couple of drinks, but that was it. I just realised that after a couple of drinks, or after the third drink, everybody just starts talking fucking gibberish. And when you’re straight, it’s really annoying. It was the first time I’d been straight since I was about twelve or something like that! It’s weird. You get all fucking puritanical, sitting there on your high horse. I thought, ‘Fuck that, man!’ Straight back to partying!!

Are you partying hard these days?

I’m a seasonal person really. I’m prolific during the winter and I enjoy myself the rest of the time. It’s worrying me that I’m coming into my writing period now. You know, if you have a book on, you just have to go with it. But if I’m seriously writing, it’s usually between October and March – six months. I think that’s why I still stay in Britain. I mean, I’ve got the money to go live somewhere nice and warm, but the truth is that I’d get no fucking writing done if I did (laughs).

Are you still hanging out with Primal Scream?

IW: Yeah. But there’s no real plans to do anything together again. I’ve been kind of hanging-out with the Alabama 3 for a long while and we’re talking about doing something together. Watch out for their new album, it’s coming out in October, and it’s called Powder In The Blood. I just got a copy burnt off and it’s absolutely phenomenal – better than the first two.

Going back to Porno for a moment, it struck me that the book could’ve been called Ching, the characters were doing that much cocaine…

IW: Well, it’s everywhere, man. It’s like crack is everywhere now. You cannot go to a respectable household now without somebody getting the crack-pipe out. And it’s funny. The way that crack was first marketed as the new heroin – you know, this is a gateway drug, one puff of this and you’re hooked for the rest of your life. And now you go to a middle class dinner party and everybody’s rocking away in the kitchen, and washing up [smoking crack].

I loved the joke about ‘washing-up’ in the book. But does it worry you that people won’t understand a lot of the drug terminology and therefore miss the in-jokes?

IQ: I don’t think so. I think a lot of Trainspotting relied on that as well. But for a lot of people it was a sort of voyage of discovery – most of the readers weren’t aware of what working class Scottish drug culture is like. They wouldn’t have known what a lot of the references were, but they could figure them out as they went. So Trainspotting almost assumed that you’d read another book first, or at least been in a certain place and lived a certain way.

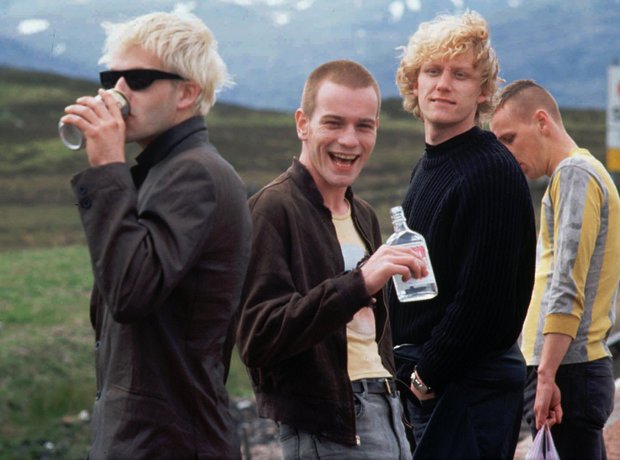

Trainspotting (1996)

Without giving away the ending, you’ve definitely left room for a third instalment…

IW: Yeah, is it the fucking holy trinity or something like that? (laughs). Maybe I’ll do a part three. I’ll probably tease for a bit. That’s the great thing about fictional characters. Actually, I was sitting on an island in Greece this time last year, wondering how I could bring Bruce Robertson [corrupt policeman and central character of Filth] back…

But didn’t he hang himself at the end of Filth? Surely he’s dead?

IW: But is he? At the end of the book, he’s hanging there, his daughter’s coming in, the tapeworm’s coming out of his arse… but what happens if the beams are rotten, and he falls and he’s taken away in an ambulance and resuscitated? Eh? (laughs).

You went to Afghanistan this year, didn’t you?

IW: I went to Afghanistan, went into Kabul. It was great. You don’t normally get the opportunity to go to places that aren’t on the tube line. You know, you’ve got a Lonely Planet guide and a Rough Guide to just about everywhere, but you won’t get one for those places. It was fantastic to see them.

You weren’t bothered by the lack of alcohol?

IW: It’s amazing the way that anywhere you go in the world, you’ll find a bar or stall serving some form of alcohol. Even in the most hardcore Islamic countries. You’ll always find it if you’re looking. In parts of Afghanistan, everybody’s on smack. They’re all zombied-out in these big party shops, they’re all opiumed-up. In Kabul there was a guy selling all this Russian vodka under the counter. So you’ve got people risking a hard time – at the very least, a whipping or a stoning or a shooting – for selling alcohol. But they still do it.

What’s your next big project?

IW: I think what would be great would be to do something completely different and away from Edinburgh for a bit, and then come back in ten years time. But you cannae really play the long ball game. You just go from one book to the next.

But isn’t this the point where you’re going to tell me that you’re giving up on writing forever, and will never publish another novel again?

IW: Oh yeah, that’s right – aye. I’m never gonna do another one again. I’m finished with writing for good. And I really mean it this time! (laughs).

RELATED

- Opinion

- 29 Nov 21

Album Review: Adele - '30'

- Opinion

- 17 Dec 25

The Year in Culture: That's Entertainment (And Politics)

RELATED

- Opinion

- 16 Dec 25

The Irish language's rising profile: More than the cúpla focal?

- Opinion

- 13 Dec 25