- Opinion

- 18 Aug 20

They have been living in Athlone Direct Provision Centre and studying in the Institute of Technology in the Westmeath town. They have been in Ireland for four years. But now, following an exhausting process, Fortunate and David Nesengani are set to be ripped from the community in which they are widely respected, and thrust into a completely uncertain future.

The Department of Justice has issued a deportation order against Fortunate and David Nesengani, a well-liked couple who are living in Athlone Direct Provision Centre.

You may ask why. The answer to that question – at least for ordinary citizens hoping for common sense to prevail – may offer fresh insights into the nature of the decision-making within the immigration office, which operates under the aegis of the Department of Justice.

For Fortunate, who is from Zimbabwe and David who is from South Africa, deportation might equal separation. Fortunate is not welcome in South Africa.

The couple have exhausted all of the ordinary appeal mechanisms available to them, and their cases are still open before the High Court, where a Judicial Review process is open to them.

One way to change what promises to be a devastating and cruel outcome, in every respect, is for the recently-appointed Minister for Justice, Helen McEntee, to intervene, and make a decision independently of her Department. The couple, both students of Social Care at Athlone Institute of Technology (AIT), are hoping for a positive final decision before the beginning of the new academic year. That way, they can focus on their studies without a dark cloud hanging over them.

Advertisement

That is also the demand of their classmates and their lecturers at AIT, who love and value them greatly.

“They might not get a date for another six months with this execution order hanging over their heads, ,” Áine Daly, the President of AIT’s Student Union says. “The longer this carries on, the more impact it will have on their mental health will get. They need clarification, so they can fully participate in their studies.”

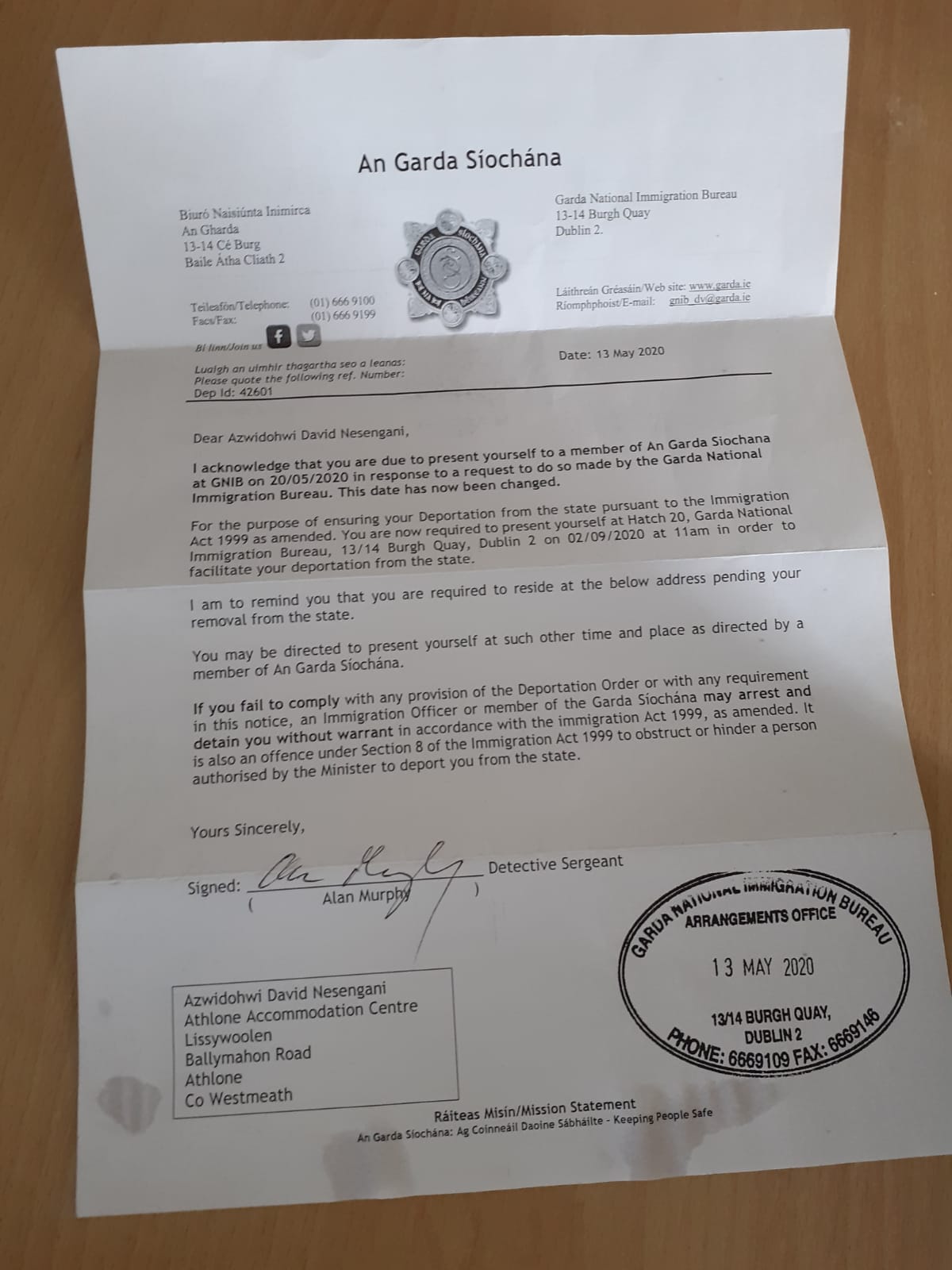

September 2nd was initially set as the day on which they would be deported.

Here, we revisit the series of events that led to Fortunate and David seeking asylum in Ireland, today.

THE FIFTH BRIGADE

On April 18, 1989, Zimbabwe’s day of independence, a squadron of soldiers arrived in the village of Zhilo.

It was a chilly afternoon, with a fresh breeze blowing, as Independence Day celebrations proceeded and soldiers marched through the town, wearing shiny smiles.

“Everyone was happy,” Fortunate, who is from the Zimbabwean village, recalls.

She was 19 at the time, meaning she was eligible to serve in Zimbabwe’s National Army.

Advertisement

In some ways, Zhilo seems like an invisible town: when you Google it, the system suggests maybe you have the wrong name. In Zimbabwe, however, even in the most lonesome areas of the country, army recruiters were capable of finding you.

That afternoon, the soldiers who arrived in Zhilo were on a double mission. Yes they were marking independence day. But what turned out to be the Fifth Brigade – an infantry branch of the country’s military, formed in 1981, as a ‘counter-insurgency’ unit – began to call into townspeople’s homes.

The Fifth Brigade had a history of identifying and killing the opponents of Robert Mugabe, Zimbabwe’s now-deceased dictator. They were also used to conscript new soldiers.

Although, there is scant information available in English online for Hot Press to unequivocally confirm that women were forced to join the Fifth Brigade, that was what Fortunate understood – and feared.

“If you didn’t join, they would sentence you to prison,” she says.

LONG WALK TO FREEDOM

On that April afternoon, in 1989, as army recruiters knocked on doors, Fortunate decided to make her escape. She didn't want to be trained as a soldier and the prospect of bloodshed and violence unnerved her.

Advertisement

She took a bus to the “edge of Zimbabwe.” She had no money.

Fortunate answers questions with the patience – and the animation – of someone who hasn’t told her story in a long time. She decided to walk in the direction of the border with South Africa. Heading from a place called Plumtree to Botswana – a hot and desert-like area in South Africa where elephant poaching has been rife in recent years. According to Google Maps, the walking distance between Plumtree to Botswana is approximately 636 kilometres.

As she walked across the country, two other young men, also fleeing Fifth Brigade recruiters, joined her. The journey was long and circuitous, but the prospect of freedom fuelled them.

The going was tough. They ate what they could find. They often had to rely on drinking cow’s milk to survive.

"Once,” Fortunate recalls, “it got so bad that I told them they could leave me in the desert to die, and just let my family know about my location.”

The young men talked her into carrying on. When the travellers finally reached the South African town of Zeerust, it was almost mid-summer.

THE POWER OF LOVE

Advertisement

When Fortunate arrived in South Africa, the country was still under the tyranny of the apartheid system of white minority rule. However, the beginning of an end to black suppression was looming. In 1990, Nelson Mandela was released and negotiations began between the African National Congress and the ruling party, under President F. W. de Klerk, to bring an end to apartheid.

Now, Fortunate’s eyes often brim with worry even when she smiles – but back then she was hopeful. In 1995, she met David Nesengani in church. David is tall, ever-smiling, and so strikingly polite that he ends all of his answers with a “thank you”.

The two fell in love, but it was not straightforward.

“I love Fortunate,” David confesses, laughing boisterously as he talks to Hot Press. “She was everything I was looking for. But people didn’t like that I wasn’t with a South African citizen. It was rare for someone to marry someone who wasn’t from South Africa.”

The reason behind locals' animosity toward Fortunate was simple yet none the less cruel: xenophobia. Theirs was a kind of forbidden love.

"They knew I wasn't from South Africa," Fortunate said.

South Africa is not, of course, along in this, but the country has a well-documented history of violence against immigrants. Last year, in one especially brutal bout of violence, at least 12 people were killed, 10 of them migrants, prompting hundreds of ‘foreigners’ to flee their homes, according to The New York Times.

Advertisement

It is believed that there is an element of scapegoating behind xenophobic attacks in South Africa. A report in the New York Times suggests that political and business leaders exploit and encourage division in the country for their own ends.

The most violent displays of xenophobia can often be seen in townships and small municipalities, where the battle for land, jobs and political office can be bitter and parochial.

David and Fortunate married in 2004 and settled in one of those small townships, Zandspruit, an informal settlement west of Johannesburg, the capital.

The issue of child education is of particular concern in Zandspruit. To help out, Fortunate set up a preschool.

“She established a crèche,” David said, “and I was becoming involved in politics. I became a liaison officer in the Government, because I’m very good at solving conflicts.”

He was a member of South Africa’s long-governing African National Congress party.

"The preschool was very successful, and it was growing," Fortunate recalls. "But people were saying that I was taking their jobs."

Local rivalries converged with a xenophobic culture to make their lives increasingly difficult. Then things turned violent.

Relatives continued to pressurise David to leave Fortunate, although – on the other side – his wife's parents embraced him "like their own son."

Advertisement

“My husband loves me, he wasn’t going to leave,” Fortunate tells Hot Press, a smile evident in her voice.

The couple paid a heavy price for opposing the purveyors of hate. They recount that locals burnt down their home. In David’s absence, they chased Fortunate, breaking her leg.

“In Ireland,” she said, “the doctor explained that they could break my leg again so that it would heal correctly, but it would be painful. My leg has healed, but it’s crooked.”

For David, that attack was the last straw.

A WELCOMING COUNTRY

In 2016, the duo arrived in Ireland. They said that they had invariably associated the country’s name with peace and warmth.

“We just wanted to finally live in peace,” Fortunate says.

Advertisement

“Everyone was so welcoming in Ireland, people would go out of their way to help us,” David adds.

However, the welcome lasted only so long. As asylum seekers, they were sent to Athlone Direct Provision Centre. The conditions there were not good, fuelling Fortunate’s decision that she would study Social Care.

“My experience in Direct Provision has been tormenting,” she says. “It’s better when you’re in jail, because you know when you finally come out. We live all these years in Direct Provision, doing nothing. We don’t have a home in Ireland, we don’t have a home at home.”

Last December, in Athlone’s Direct Provision Centre, Fortunate saw an asylum seeker die in David’s arms. He was a good friend of the couple, and Fortunate says the experience scarred her. She tells the story carefully, but with a hint of anger.

“He just collapsed,” she recalls. “He said he had a pain in his chest. He told my husband to hold his hand – we were thinking: he’s talking. How can a person who was just talking wants to die?

"After my husband held his hands, he passed out. And then the ambulance people came and resuscitated him. Then he asked my husband to remove his shoes and asked for a glass of water. Then he passed out again, and they couldn't resuscitate him anymore. It was very traumatic."

The couple helped out with the arrangements following the man’s death.

Advertisement

Shortly after this incident – in a week when Fortunate was feeling 'depressed' and 'suicidal' – two men knocked on their door.

"I was crying throughout that week,” she recalls. “They came to my room. They found me sleeping. They were two men, one of them said, ‘Are you Fortunate? We are here to say thank you for everything you have done concerning the death of the man. People like you; we really need in the community’.”

Later, the staff and residents at the centre told Fortunate that the man was the then-Minister for Justice, Charles Flanagan.

Whether the Minister knew it or not, at the time of his visit, the couple were already fighting a deportation order.

DEPORTATION BLUES

So, we arrive back at the central question: why are they being deported?

Fortunate and David say that a series of misunderstandings has led to the International Protection Office (IPO) – the unit at the Department of Justice in charge of granting asylum – to accuse them of lying about their plight.

Advertisement

Fortunate says that they had accused her of miscalculating the distance from her village in Zimbabwe to the town. Her interpreter, she said, had also mistakenly told her interviewers that her leg was amputated. "Even though I corrected them,” she says now, “I said fractured. They still said I was lying."

IPO had interviewed the couple separately to make sure their stories were in line and consistent. This had also led to confusion, Fortunate says.

“They told me ‘Why you didn’t tell us about your husband’s politics?’ – but I thought we had to tell our own stories,” she says.

Fortunate and David have lost several family members as a result of the coronavirus crisis in South Africa. With more than 580,000 confirmed cases, the country has more than half of all reported cases in Africa.

Meanwhile, the wheels of so called justice grind on. The couple were before a ‘tribunal’ recently, where the judges agreed that the deportation order was just.

So is there anything that can now be done?

Advertisement

HEARTBREAK IN ATHLONE

The community in Athlone – and especially the couple’s friends in AIT – are heartbroken to learn of the predicament in which David and Fortunate find themselves.

David is a final year student of Social Care in AIT: he explains that he cobbled together his registration fees by volunteering in the community.

“Even if you’re volunteering, people would give you €20 or €10,” he says.

Later the Irish Refugee Council, impressed by his academic determination and passion for social care, helped him with tuition fees.

“I always liked to learn,” he adds.

David already had a leadership and politics diploma from South Africa. As part of his college course, he has worked in a nursing home and offered social support to troubled youth in the country.

“I love working with younger people. I like to understand them, and speak their language,” he says.

Advertisement

Fortunate has also recently finished a course which will allow her to enrol as a first-year social care student.

Áine Daly, told Hot Press that she is hoping that the Minister for Justice will relent and stop the deportation.

For now, she says, the Department of Justice has responded to a letter from AIT’s President, Professor Ciarán Ó Catháin, promising that the couple are not facing an imminent threat of deportation.

The letter, seen by Hot Press, states that “there are ongoing legal proceedings before the High Court in relation to these cases.”

“While I can’s comment on the specific details, I can advise that there is no imminent risk of deportation in either cases,” Oonagh Buckley, the Department’s Deputy Secretary General wrote.

She also asked AIT students to ‘re-consider’ a protest outside the Dáil by AIT’s Student Union that had been organised for this Tuesday “in light of the above information”; and “in view of the ongoing risk posed by the current pandemic and the public health advice.”

Áine Daly says the protest has been called off – for now.

Advertisement

She reflects on the fact that Fortunate has made masks during the pandemic for people in the community. David’s kindness and passion for giving, has also touched the hearts of many in Athlone.

Áine, who is herself a Social Care graduate, says that the community raised funds for the couple in the past and that AIT is hoping to educate people on “what Direct Provision really is.”

“A lot of human rights violations are happening in Direct Provision centres,” she says.

“David and Fortunate have integrated into our community. They are members of our community, and sending them back to South Africa during the pandemic is very cruel. This should not be happening.”

The Students Union at DCU has also issued a statement urging the Government to revoke the deportation order.

“[We] stand in solidarity with our friends in [AIT Student Union] as they experience what we have seen happen repeatedly at the hands of the Government: unjust deportations. DCU sends its thoughts to David and Fortunate, and calls on the Government for immediate action.”

VOLUNTARY RETURN

Advertisement

A spokesperson for the Department of Justice has told Hot Press that all unsuccessful applicants for international protection are actively encouraged to ‘voluntarily’ leave the country “prior to a deportation order being made.”

The Department says that, in addition to the option of challenging the decision in the High Court through a judicial review – an expensive process that most migrants can’t afford – asylum seekers can, under Section 3 (11) of the Immigration Act of 1999, ask the Minister for Justice to “revoke or amend” the deportation order.

“Persons who leave the State voluntarily preserve the right to enter the State at a later date, with a valid basis,” the spokesperson says. “They may also avail of assistance from the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) in obtaining travel documentation as well as covering the financial costs of travelling to their country of origin.

“In addition, a small integration grant may be available in certain circumstances to help cover the costs of income generation activities such as education or business set up in their country of origin.”

The spokesperson for the Department adds that those who refuse to take up the ‘voluntary return’ offer “are obliged to remove themselves from the State and to remain outside of the State.”

That is the law: what French writer Victor Hugo famously described as a “machine that cannot move without crushing someone.”

As for David and Fortunate, they are cautiously optimistic. They say that they believe that the Minister, Helen McEntee, has “the compassion and humbleness” in her heart to allow them to call Ireland home, perhaps for the sake of love.

Advertisement

David says that, as long as you have someone to love, you have something to hope for.

![Minister James Lawless: "How do we have two different rules [for alcohol and marijuana]?" Minister James Lawless: "How do we have two different rules [for alcohol and marijuana]?"](https://img.resized.co/hotpress/eyJkYXRhIjoie1widXJsXCI6XCJodHRwczpcXFwvXFxcL21lZGlhLmhvdHByZXNzLmNvbVxcXC91cGxvYWRzXFxcLzIwMjVcXFwvMDRcXFwvMDMxNzA1NTZcXFwvTWluaXN0ZXItRURVLWJ5LUFSLTI2LmpwZ1wiLFwid2lkdGhcIjpcIjMwOVwiLFwiaGVpZ2h0XCI6XCIyMTBcIixcImRlZmF1bHRcIjpcImh0dHBzOlxcXC9cXFwvd3d3LmhvdHByZXNzLmNvbVxcXC9pXFxcL25vLWltYWdlLnBuZz92PTlcIixcIm9wdGlvbnNcIjp7XCJvdXRwdXRcIjpcImF2aWZcIixcInF1YWxpdHlcIjpcIjU1XCJ9fSIsImhhc2giOiI5Nzg2MDBhOGZkZTdmZjcwMGM3ZDE5MDdkZjhlYmE1MmQ3YjAzZjMwIn0=/minister-edu-by-ar-26.jpg)