- Opinion

- 14 Apr 22

World Exclusive: The Early Poems That Set Bob Dylan On the Road to a Nobel Prize In Literature

Hot Press has been given first access to the text of a collection of Poems Without Titles, written by songwriting genius Bob Dylan at the age of 18, shortly after he left high school. Irish fans of the man from Minnesota will be glad to know that Ireland’s greatest novelist James Joyce gets a namecheck in a collection where Beat Poetry meets Classical Epigram...

In September 1959, Robert Zimmerman, who had been graduated from Hibbing High School that June, traveled south about 190 miles to Minneapolis to begin classes at the University of Minnesota. He took a few classes and halfheartedly pledged a fraternity before leaving university the following year. His primary education came in 1959 and 1960 in the funky, artsy neighborhood called Dinkytown, near the university. Zimmerman had had a band since high school, when he and a group of friends performed as the Golden Chords.

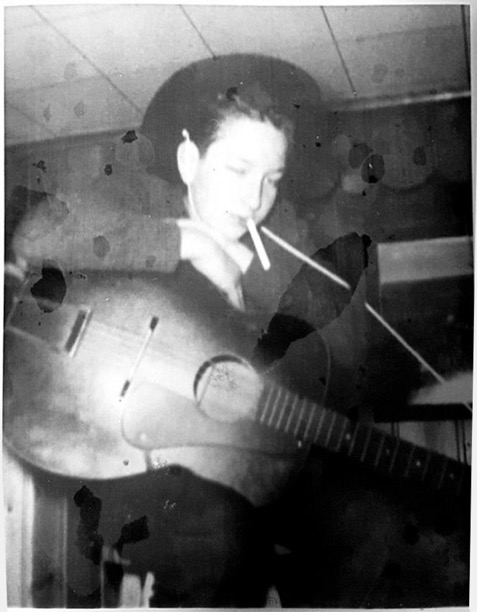

Now he preferred to take a stage alone, with his acoustic guitar and a harmonica. He participated in the local folk and traditional sessions in coffeehouses and bars. One evening, before an appearance at the 10 O’Clock Scholar on 5th Street at 14th Avenue, Zimmerman announced his name as “Bob Dylan.”

Soaking up ancient ballads from the islands and highlands in the company of new friends like Minneapolis musicians John Koerner, Tony Glover, and Dave Ray, and reading voraciously in literature and American history, Dylan was also beginning to write his own material. His leading influences were the Beat poets currently in the vanguard of the avant-garde: Gregory Corso, Allen Ginsberg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and – though he’s best known for his prose – Jack Kerouac. Together with the Beats, Dylan was also getting to know their forebears, like W.B. Yeats, Walt Whitman, Edgar Allan Poe, and classical poets including Martial, Juvenal, and Ovid, who he’d first encountered in his Latin Club at Hibbing High.

Gregory Corso, who read Greek and Roman poets as a teenager in prison at Clinton Correctional, and later at Harvard, is particularly important as a bridging figure. Allen Ginsberg, later Dylan’s friend and immense admirer, was a historian of poetry, and amassed his own influences from all countries and centuries. Ginsberg once told me that the last time he traveled to hear another poet read was when he flew to Ireland in 1994 for Michael Hartnett, and that his favourite poem in English – not by himself, he chuckled – was the anonymous medieval lyric “I Sing of a Maiden.” “Howl” and “America,” both published in 1956, were contemporary works when Dylan was in college.

Some time in 1959 or 1960, Bob Dylan gathered together sixteen sheets of free-form, Beat-styled poetry under the cover page “Poems Without Titles.” These poems, written when Dylan was still a teenager, are among his earliest works. Poems Without Titles first became known in 2005, when they were consigned to Christie’s by an anonymous owner. They were exhibited in a limited fashion at the Experience Music Project in Seattle that summer, in advance of the Christie’s sale, sold in November 2005 for almost $80,000, and vanished again until now. RR Auction have rightly showcased the Poems Without Titles, divided into separate lots, in their “Marvels of Modern Music” auction from May 12-19th.

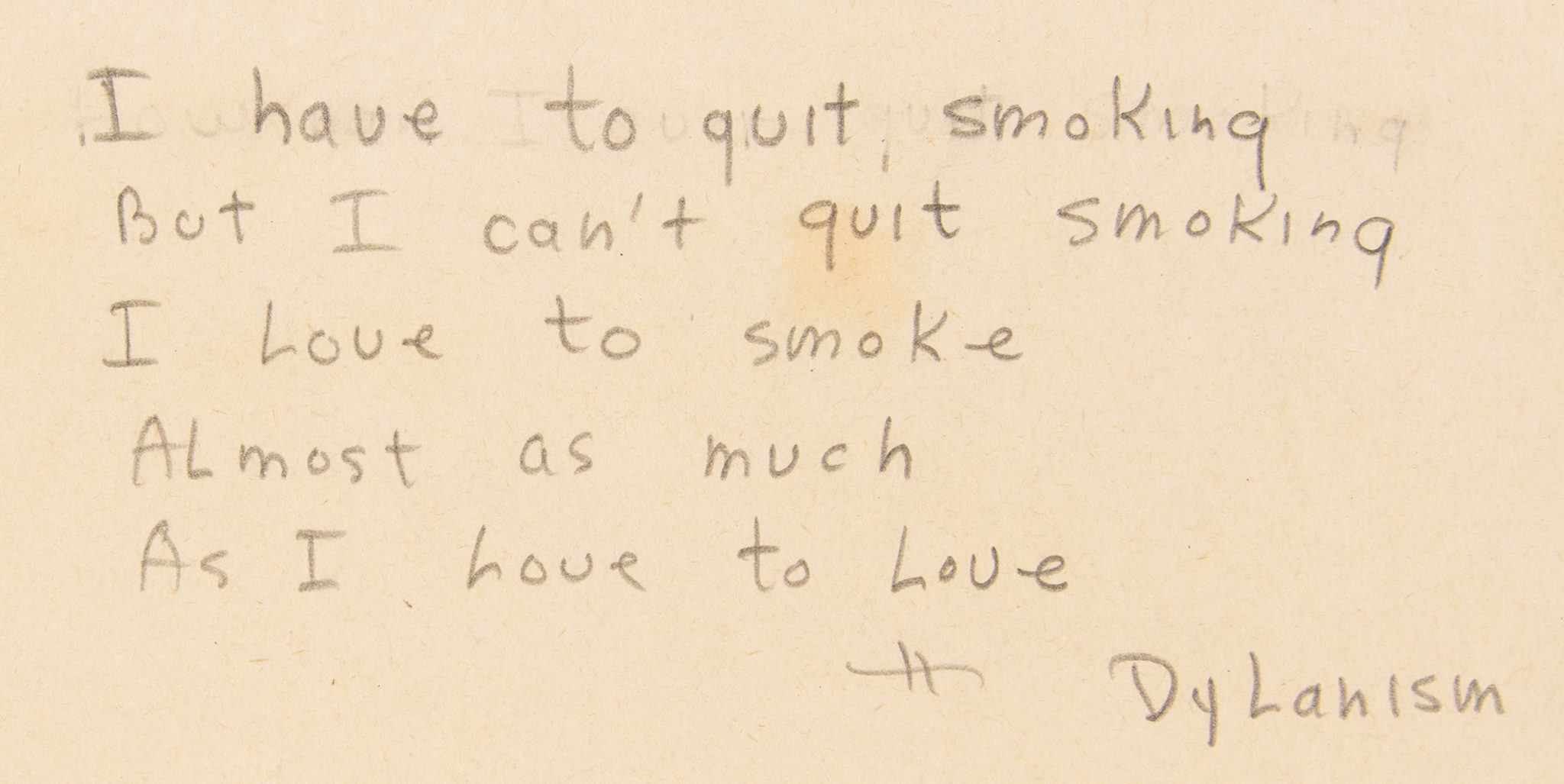

I do not know the provenance of these poems, and Christie’s have not answered requests for one. However, when a few pages were shown in Seattle, they were said to have been “rediscovered” by a man who was a fellow student of Dylan’s at the University of Minnesota. Handwriting experts have established that they are in Dylan’s writing, and – having spent many weeks looking at it in various libraries and archives – I agree. He’s pretty fascinated with the brand-new name he’s chosen, signing “Dylan” to many of the poems, and referring occasionally to a shorter, pithy, epigram-style verse as a “Dylanism.”

Poems Without Titles are a riot and a romp, fuelled with youth and zest and a wickedly sharp mind. They’re also surprisingly reflective – well, perhaps not surprising, considering the writer. Still a teenager, Dylan is already thoughtful, noticing both the glory and the ugliness in the world around him, musing upon machines and music and, yes, Muses. The longest poem is a chronicle of young women who have caught his eye and heart, from Judy and Ione to Carol, Barbara, Adele, and Judy again:

Once upon a time there was

JUDY

And she said

Hi to me

When no one else

Could take the

Time—

And she was small

And cute—and tempting

And I thought I

Loved

Her

And I wrote to

Her

Christie’s identified “Judy” as Judy Rubin, who was at summer camp with Dylan in the mid-1950s. There may be correspondences with other girls Dylan knew in his school days, like Ione, who sat behind him in Speech class – and Barbara, who is the star of this poem, physically gorgeous, who loves him back, and whose parents even like him:

She had freckles

But, man,

She could Love

She could Love

Like no one else could Love

And she loved

Me

And

Only

Me

And I ached

For her love

Then she moved

Far away—

Gone—so Gone

Like no one else

Had ever gone

Before

And she found

Someone new

A thousand miles

Away

And I died

Oh God

How I died

Seela

There’s a lot of genuine sorrow in that ache, in the beatnik lament of “Gone—so Gone[,]” and the repetition of “I died” before the Hebrew-scriptural pause marker of “Seela,” which appears throughout the poem to divide its stanzas. In his 1986 biography No Direction Home, Robert Shelton recounts Dylan’s infatuation in 1957 with Barbara Hewitt, a Hibbing girl who had just moved to a Minneapolis suburb. Hewitt’s black-and-white wedding photograph shows a smart-eyed young woman with a brilliant smile. Perhaps the freckles indicate that Barbara was a redhead, which could provide a long-ago basis for the imaginative thread of a beautiful redhead running through Dylan’s later songs.

Courtesy of Dag Braathen

Even in his earliest days, though, Dylan may or may not be using real names. Readers should always beware this as an artistic possibility with any poet, or songwriter, and particularly with Dylan. The poem ends powerfully, and with reference to no woman:

And my

Circle starts

over…

But it’s not

Me

That’s living it

No, man, I’m

Just

A

Part of the circle

I’m a symbol

I’m a piece

But unlike

The people,

I don’t fit in anymore

I’m lost

And my trouble is….

I know it—

Dylan

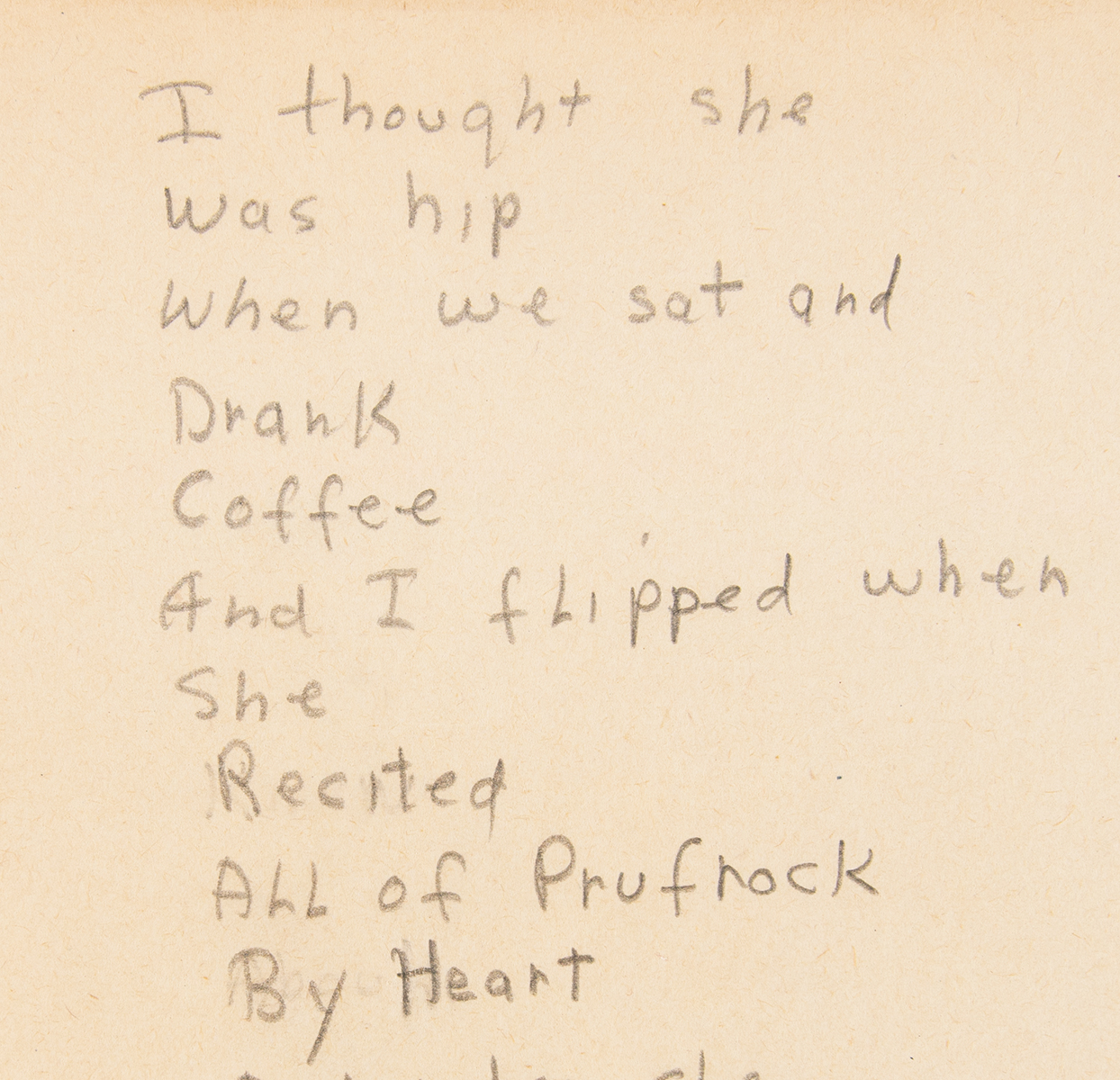

The clues as to what Dylan has been reading in college are grand to find. One funny poem recounts a bad coffee date; the speaker “flipped when / She / Recited / All of Prufrock / By Heart” but is literally sickened when she expects him to open a door for her. Surely Dylan has had a love/hate relationship with T.S. Eliot for decades.

I’d agree that ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’ is Eliot’s pinnacle, with the epic crash of ‘The Waste Land’ a weighty second. Eliot makes a cameo appearance fighting with Ezra Pound near the end of Dylan’s own epic, ‘Desolation Row’ (1965). And Dylan chose to read a long stretch of the beginning of ‘The Waste Land’ in an episode of his satellite radio show Theme Time Radio Hour – emphasising with a particular relish the coffee date in the Hofgarten.

Courtesy RR Auction and © Babinda Music 2022.

Courtesy RR Auction and © Babinda Music 2022.In a longer poem, Dylan drops the line “and I felt like an / Idiot child trying to read James Joyce in the dark[.]” Joyce’s autobiographical A Portrait of The Artist As A Young Man underpins a couple of the Poems Without Titles as much as does the work of any poet. Stephen Dedalus, the title character of Portrait, is rather obsessed with the flaws, failings. and appetites of his own body, and the smells of Dublin, particularly the sharp ones. Among Stephen’s earliest memories is wetting the bed; later, he’s comforted by the reek of “horse piss and rotted straw,” a “good odor to breathe.” In Ulysses, Stephen’s handkerchief and the sea are both “snotgreen.”

In the Dylan poem mentioning Joyce, a guy named Humphrey, who is urinating, is the basis for much humour. In another, a coffeehouse session is disrupted for the speaker, the only one who seems to notice, by someone copiously blowing their nose. The snot on the floor blends “into / The atmosphere / Of soul sending / Sounds[.]” In one short poem, Dylan even riffs off another Joyce, the American poet Joyce Kilmer, and Kilmer’s immensely popular 1913 poem ‘Trees’.

What [the hell]

Kind of

Place

Is this

When

A man

Can’t love

A simple tree

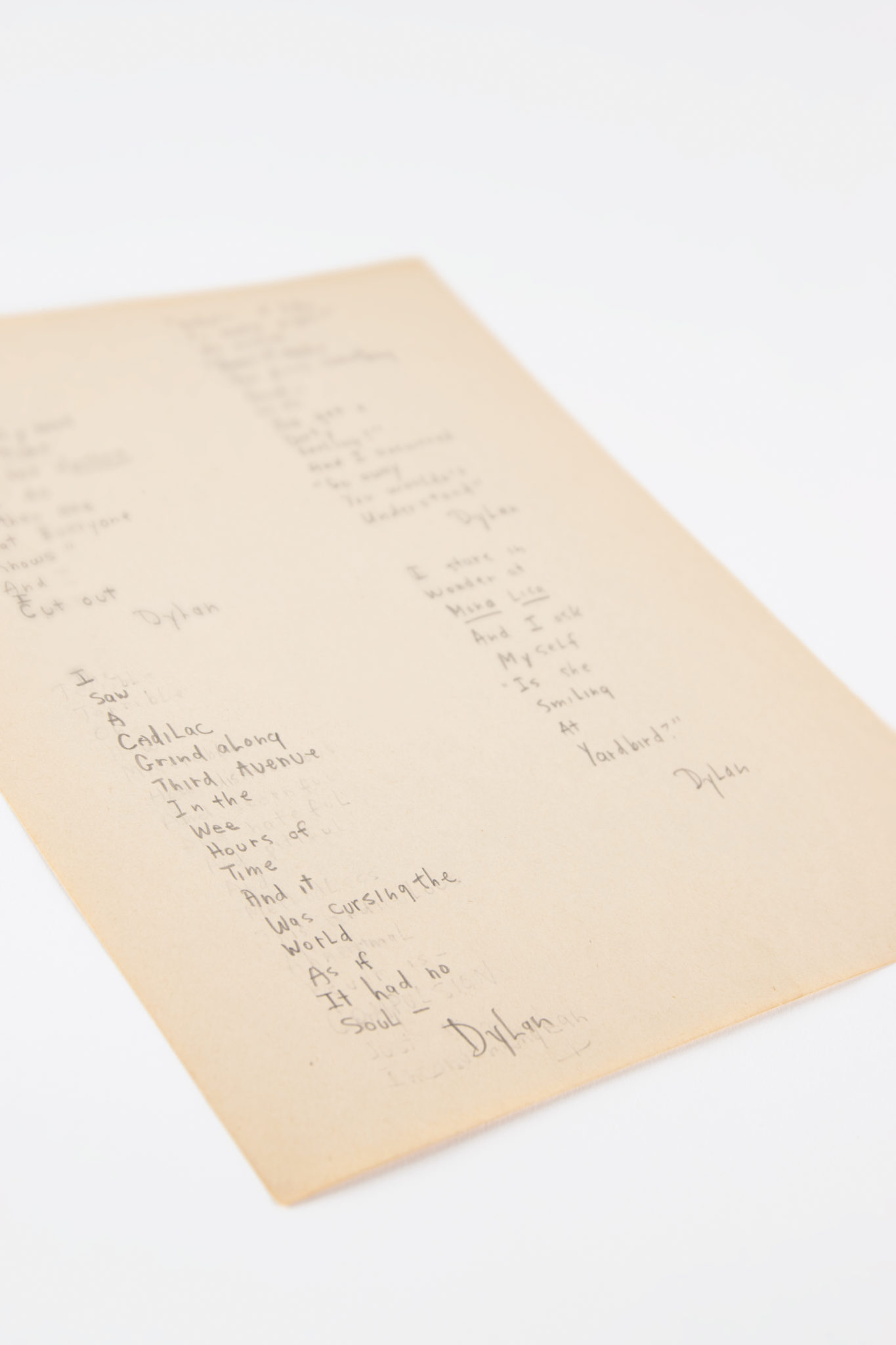

Two vehicles already matter enough to Dylan to be included in his poems: the Cadillac and the motorcycle. Already immortalised in song in hits like Mildred Jones’s supremely dirty ‘Mr. Thrill’ (1954) and Chuck Berry’s ‘Maybellene’ (1955), and well known to be the favourite car of Dylan’s childhood idol Elvis Presley, the Cadillac was an all-American symbol of wealth, success and cool.

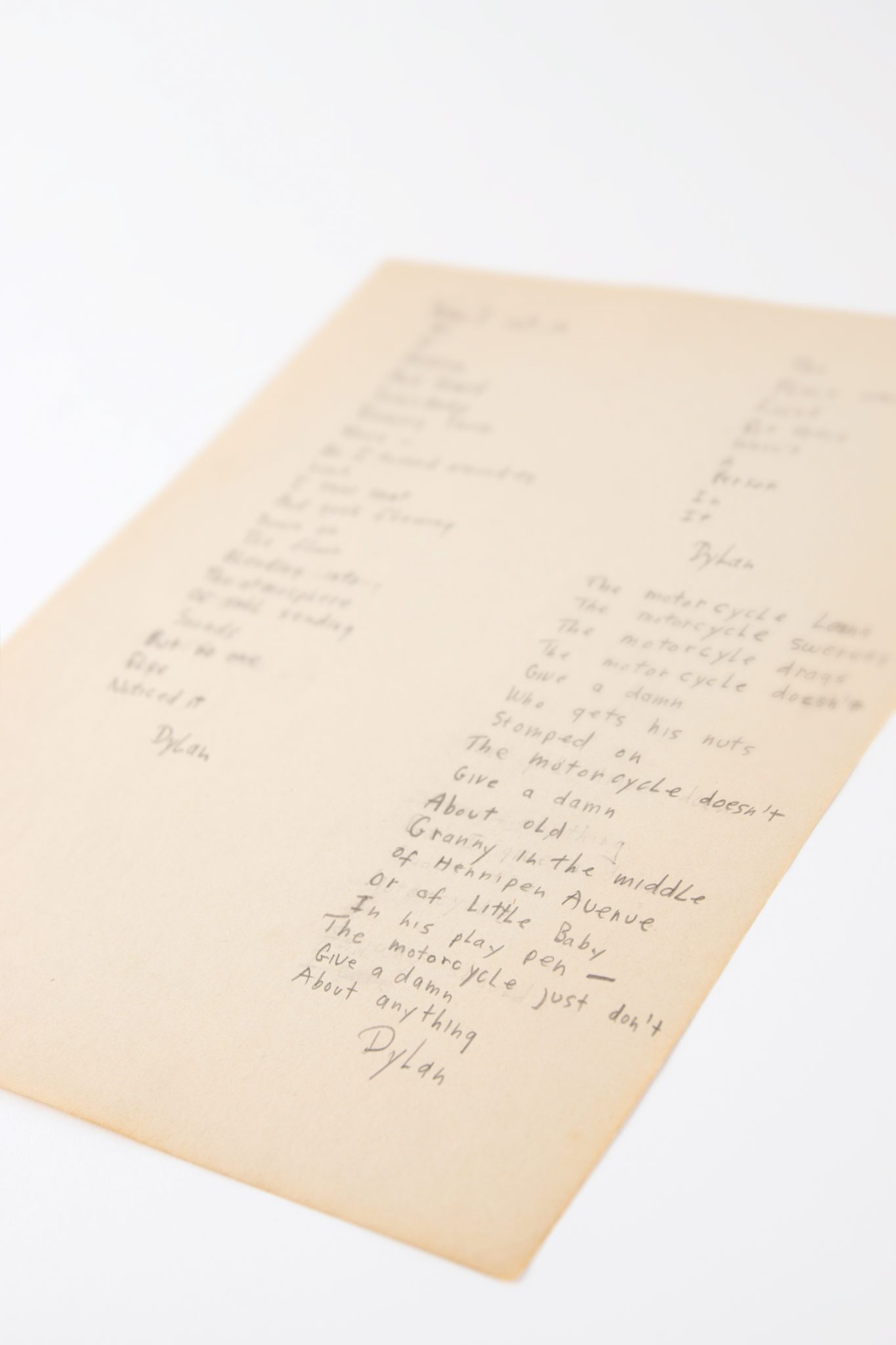

Dylan had a cherry-red Cadillac convertible when he lived in Greenwich Village in the early 1970s; Larry “Ratso” Sloman vividly remembers Dylan driving, and “swerving all over the Village” in it, late one night or early morning in 1973. Dylan would feature the Caddy in songs like ‘Talkin’ World War III Blues’, ‘Summer Days’, and ‘I Contain Multitudes’. He devoted an episode of Theme Time Radio Hour to Cadillacs, and did a commercial for the make’s Escalade model in 2007. Here, in his early poem, the Caddy is a soulless thing, grinding “along / Third avenue / In the / Wee / Hours of / Time[,]” cursing the world. The motorcycle is an even scarier machine, hazardous to old grandmothers and babies alike, careless and uncontrollable:

The motorcycle just don’t

Give a damn

About anything

Dylan

Courtesy RR Auction and © Babinda Music 2022.

Courtesy RR Auction and © Babinda Music 2022.Here are the seeds of “Motorpsycho Nitemare,” of “a bad motorcycle with the devil in the seat / Going ninety miles an hour down a dead end street,” and perhaps the “motorcycle black madonna / Two-wheeled gypsy queen.” Here, too, is a pursuit Dylan himself famously enjoys, one providing solitary time and ultimate freedom. He’s long brought a trailer of motorcycles with him on the road as he tours – and, mercifully, has had no known incidents riding, since his widely reported 1966 accident on a Triumph near Woodstock, New York.

The young fella, live on stage (with cigarette). Courtesy of Dag Braathen

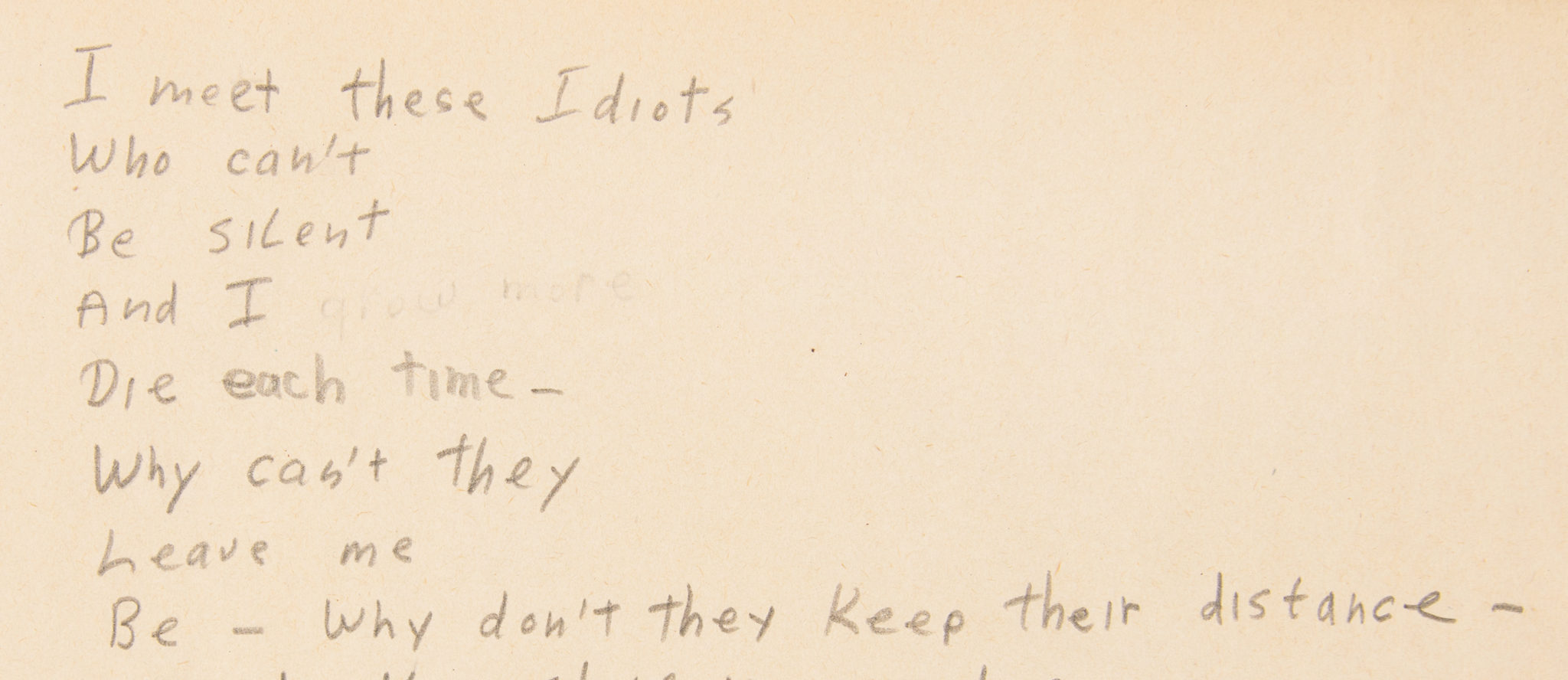

Fame is already in the offing – as Samuel Beckett put it best, in that marvellous sneering phrase from Krapp’s Last Tape, “getting known.” Dylan wants it, but, already, he doesn’t like it. This is a young man who is never going to submit with a smile when talking to reporters, being photographed, being approached. Being peered at, talked about, and speculated upon in Minneapolis coffeehouses is horrible to him, from the very beginning:

Why don’t they keep their distance—

Why do they stare in wonder

And ask

“Do I know him?”

Or something like

“I know who he is!”

What a goddam vicious

Circle.

To

Live in.

Courtesy RR Auction and © Babinda Music 2022.

Courtesy RR Auction and © Babinda Music 2022.Similarly, this short lyric packs a long punch, in terms of the feeling of remaining alone in a crowd:

The

Place was

Filled

But there

Wasn’t

A

Person

In

It

Dylan

On his current Rough And Rowdy Ways Tour, Dylan is smiling into the crowd from the stage after his shows – that is, when fools with cellphones aren’t flashing them in his face after being asked in every possible way not to. He’s downright genial in his interactions with the men in the band. The packed venues are certainly full of happy people listening; I hope he’s happy up there on stage, too.

Courtesy RR Auction and © Babinda Music 2022.

Courtesy RR Auction and © Babinda Music 2022.* * * *

“The Child is father of the Man,” William Wordsworth wrote. He isn’t Bob Dylan’s favourite Romantic poet – that laurel goes to George Gordon, Lord Byron – but Wordsworth is right that we as adults are all shaped, for better and for worse, by our child selves. The joy of these Poems Without Titles is that they show a future Nobel laureate in Literature at the very start of his public life as a wordsmith. Just eighteen, Dylan already contains multitudes. He celebrates the new name he’s chosen, refers back to Jewish spiritual texts he’s grown up hearing and speaking, writes in a style like the cutting-edge counterculture Beat poets of Manhattan and San Francisco while also trailing centuries-old clouds of other literary influences, and turns out some highly original and unique inward thoughts and self-reflections.

Courtesy RR Auction and © Babinda Music 2022.

Courtesy RR Auction and © Babinda Music 2022.Dylan hasn’t changed as an artist over the decades as much as he has gone from strength to strength. He never shuns or lays anything aside; he might want to use it later, in a new way. His creativity is both wide-rangingly knowledgeable, over many cultures and their arts, and also individual and personal.

My hope is that the Poems Without Titles will end up where they belong, in the Bob Dylan Archive in Tulsa, Oklahoma, as part of his earliest work collected there, preserved and protected in time to come.

*All material by Bob Dylan appears with the permission of Babinda Music and is © Babinda Music 2022

For further info visit RRAuction

RELATED

- Opinion

- 30 Aug 22

Bob Dylan: What Happened When the Rough and Rowdy Ways Tour Hit Denver

- Opinion

- 09 May 22

Take Me Back To Tulsa: The Bob Dylan Archive Is Open, May 2022

RELATED

- Opinion

- 26 Dec 21

MOST READ 2021: Bob Dylan - In A New York State of Mind

- Opinion

- 21 May 20