- Sex & Drugs

- 27 Jun 19

Dubbed the Howard Marks of Munster, Brian O’Rourke was landed with a jail sentence back in 2008 for smuggling cannabis. Eleven years later, he’s part of an RTE documentary, which sees a number of artists competing to showcase their work at the prestigious RHA Exhibition in Dublin. Here, Brian tells his fascinating story...

“I’m on record as having been the biggest cannabis supplier in north Kerry, north Cork and west Limerick.”

It’s a hell of a statement for 51 year-old Limerick man Brian O’Rourke to make. Then again, O’Rourke has taken on numerous identities throughout his life and this is just one of them. Back in the 1980s, when he was a youngster, he ditched his provincial hometown of Shannon and fled across the Irish Sea to London. He lived for a decade or more there, hanging out in some of the shadiest areas of the English capital.

At different times, he defined himself as a ‘punk’, an ‘activist’, and a ‘counter-culturalist’. Inside, he was still Brian O’Rourke and he was doing what most of us spend a good part of our lives at: he was looking for love. After meeting the woman of his dreams, in the 1990s he got married and moved back to Ireland, where he took on the mantle of ‘husband’ and ‘father-of-two’.

Work wasn’t exactly easy to come by for a perennial outsider. To put food on the table, Brian made the decision to become a cannabis smuggler. He had no qualms about it. It may have been illegal but he had lived in a dope smoker’s milieu. It was an essential part of life as he knew it. During his heyday in the early 2000s, Brian became known as the ‘Howard Marks of Munster’. Inside, he knew that it couldn’t last forever. He was right. It might sound like a cautionary tale, and it is. In 2008, he was caught by the Gardai with €18,000 worth of cannabis.

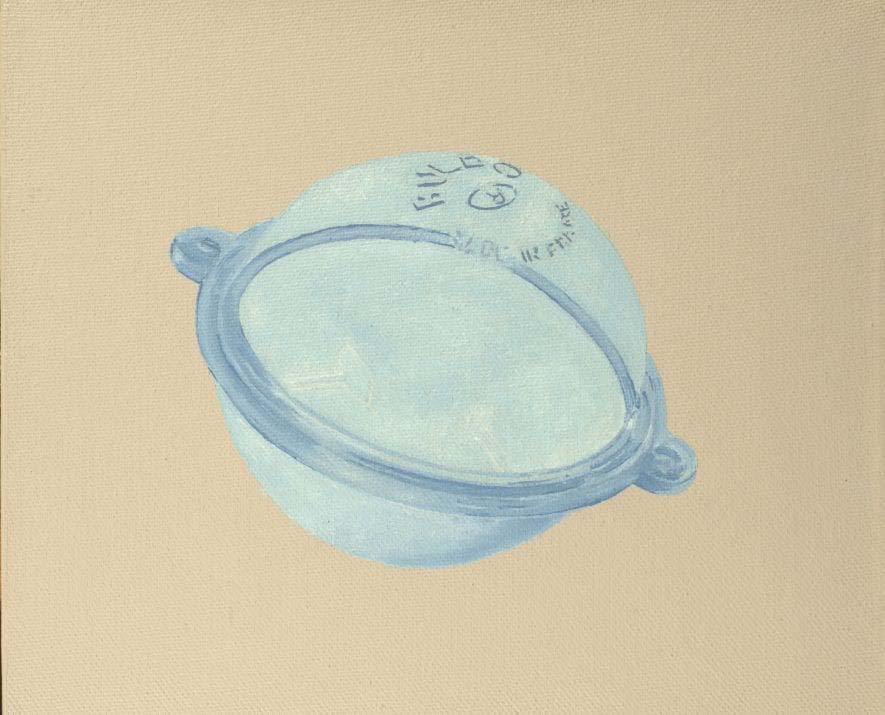

In 2009, Brian O’Rourke was jailed for four years for ‘possession with the intent to supply’. He became an inmate of Limerick Prison. Separated from his family for the first time, Brian threw himself into the prison education system. He re-discovered a flair for painting, combining his interest in fishing, as well as his concerns about the environment, into art.

Advertisement

Now, seven years after leaving prison, Brian has assumed a different identity – or two. ‘Graduate of Limerick School of Art & Design’ seems to fit very well. ‘Finalist for the Royal Hibernian Academy’s 2019 exhibition’ does too.

So where did it all go right?

Peter McGoran: How did you become a drug dealer?

Brian O’Rourke: I moved back to Ireland from London when my eldest son was born. We ended up settling in a town called Abbeyfeale. That town had its own type of off-the-grid community, the type of area they’d tag as ‘badlands’ back in the day. It’s was also a seriously economically deprived area, which meant work wasn’t as forthcoming as it should be. Us being punks, we were maybe too outside the box to make good money either. I got a trade painting and decorating, but that wasn’t paying the bills. The cannabis scene in the country at that time was pretty dire. So I decided to become a drug smuggler.

How did the operation work?

(Pauses) I can’t got into it that much because I don’t know what the statute of limitations is! Suffice to say that back in 2008 I got caught with 18,000 euros worth of weed.

How were you caught?

Advertisement

I was ratted out, basically. But that was kind of consequential in my view. This business is a finite thing anyway, that’s what I’ve learnt. Whether it was me getting caught or being ratted out or whatever – it was going to come to a head anyway.

Why is that?

This country’s too small. If you do something like selling cannabis, you really are putting your head above the parapet.

Did you have any ethical issues about what you were doing?

Well, put it this way, my father’s an alcoholic and I had a bit of trouble with alcohol myself – and I’ve always felt that cannabis was conducive to a lot of people in ways that alcohol wouldn’t have been. I had a belief in what I was doing. I’ve seen the consequences of heroin. I’ve seen the consequences of alcohol. We’re now living in a time of medication abuse. But cannabis is more of a safe bet.

Were you ever afraid of the people you were dealing with?

No, because everyone I was dealing with came from that counter-culture scene where you vouched for each other, without crossing over into really serious criminality. We were offsetting ‘gangsterism’.

Advertisement

Were you worried that your lifestyle might make it obvious that you were involved in an illegal business?

I kind of understood that – being in a small community in a small province, it becomes fairly obvious after a while what you’re at. You accept that it’s going to have to come to a head.

Did you worry about being targeted by other drug dealers or by the Gardai?

You always have that paranoia with you – that ‘eyes half open’ ethos. I’ll put it this way, when I stopped, it was like regressing back to the mentality of a 12 years old. You feel like you don’t have a care in the world.

Was there a risk of you invading someone else’s patch to expand your business?

No, that didn’t really exist in the culture of our neighbourhood. We were able to say, ‘This is what we deal in – and we don’t deal in this other stuff’ – nothing with chemicals, no heroin.

How do you know how to trust and who not to trust?

Advertisement

The business always involved friends, or friends of friends. Even though the circles gradually got bigger, the way to do it was to always have friends of friends. Everyone’s accountable. You can’t allow for individuals. Unfortunately, I did at one point, and that’s where I came to my end.

What effect does jailtime have on your family?

It’s infinitely worse for them than you. They do more time than you. I’d never been away from my family before. I’d never been in jail. To get a four-year sentence was a pretty stiff one in my case. Even up until sentencing, I had this kind of stupid belief that I was semi-in the right. But the law is the law, and until it changes – you’re breaking it.

Were you treated fairly by the Irish criminal justice system?

Yeah, absolutely. I could see that these were people going about their jobs. This was the Irish prison system, not the American system. You’re dealing with people that you might talk to on the outside. I could say, ‘If I didn’t know that fella was a prison officer, we’d have a healthy conversation’.

What were your first impressions of prison?

I think it’s a bit like that step up from primary school to secondary school! (Laughs) You know that first day of secondary school when it’s absolute chaos and you’re trying to get the measure of it and you’re the rabbit in the headlights.

Advertisement

Were there people there trying to exert their authority on the newcomer?

(Pauses) Ahhh, yeah… That’s a hard one now, because you and I both know how things are run. But when I went in I was treated OK. I had no real complaints, because I’d been doing what I was doing for a while and there were some people who knew me or knew of me. (Pauses) But it was the impact on my family I was worried about. I honestly didn’t think of much else.

Was there a moment were you said, ‘I want to reshape my life’?

Before I’d even got sentenced, I’d kind of mentally prepared. I was going through the AA for alcohol abuse, and that process creates some self-awareness, saying ‘What am I doing?’ The other thing was that there was a school for prisoners. It wasn’t just going to be a prison yard. I straight away saw this as an opportunity to go, ‘OK let’s see what we can do’. I was really taken aback as to how well-provided the prison was.

There’s a debate: should prison be a deterrent or a place for genuine reform. Do you feel ‘reformed’?

Without a doubt. It’s definitely changed me. In some ways it is a deterrent because you have the primal fear of going back there, but I can honestly say that, as a person, I’ve evolved from prison.

What does it do to you not to be able to have sex?

Advertisement

(Laughs) Initially that’s not a concern. But yeah… Obviously, base needs and all that. I was lucky that I ended up in a single cell. That’s all I want to say!

When did you decide to take up art?

I went into the prison school and there was an art teacher there. He had long hair and a beard and I clocked him right away as someone I could relate to (laughs). I told him I used to draw and he said, ‘Well why don’t you try some painting?’ ‘Can’t do that. Never done that’. ‘Sure you can. C’mere we’ll get you set up’. He was the most easy-going man. And when you get into the school there, it’s like getting out of the prison. It’s such a different environment from the landings or the yard. And the other prisoners there respect that environment.

When did you discover you had real talent?

All my experience as a radical leftie and everything in my past… it was like it all colluded together into this understanding. To then be able to just paint made sense to me. But it’s funny. They’re crafty in that school. They’ll have you doing exams without even realising it. Then by the time the end of year comes around they’ll hand you a sheet of paper and say, ‘Well done, there’s your Leaving Cert!’

You went to college.

Advertisement

I left prison and did a VTOS programme, then I got into the Limerick School of Art and Design. Everything snowballed. I graduated in June 2018 with an honours degree – my son graduated the year before I did! Then my name was put forward by the head of LSAD, Mike Fitzpatrick, and also by the head of the prison education department, Tom Shortt, to the RHA. That’s what’s led us to here!

What’s your attitude to legalising cannabis?

We’re a very conservative country and I kind of accept this, but it’s gradually getting more liberal. These last few referendums have shown that. There seems to be a domino effect. Maybe I’m too optimistic, but I think that in my lifetime we’ll see cannabis legalisation.

What would you say about the ‘war on drugs’?

When I started dabbling in cannabis, I was one of the few. Nowadays, you’re one of the few if you don’t dabble in cannabis. It’s a sign of the times. We have to evolve. You can focus on better treatment for people who feel the need to jump right off the tracks. Or better yet, focus on the heroin problem. Focus on the abuse of medication. It’s a war on people, not a war on drugs. A lot of us are living proof that you can partake, or be part of, that culture without being involved in gangsterism.

Was there a particularly great high that will always stick with you?

The biggest high that I’ve ever experienced was the birth of my sons. It transcends everything. But as far the other stuff goes – I had ice-o-latar hash in Amsterdam 15 years ago and it turned my eyeballs north to the point where I thought I was blind and my wife couldn’t stop laughing at me. That wasn’t bad either!

Advertisement

Exhibitionists: Roads to the RHA, featuring Brian O’Rourke, will be aired on RTE One tonight, June 27.

![Drugs Minister Colm Burke: "I mean, no matter what area you go to, whether you go to talk to a group of solicitors or barristers or doctors, nurses, care assistants – a certain percentage would have [tried drugs]" Drugs Minister Colm Burke: "I mean, no matter what area you go to, whether you go to talk to a group of solicitors or barristers or doctors, nurses, care assistants – a certain percentage would have [tried drugs]"](https://img.resized.co/hotpress/eyJkYXRhIjoie1widXJsXCI6XCJodHRwczpcXFwvXFxcL21lZGlhLmhvdHByZXNzLmNvbVxcXC91cGxvYWRzXFxcLzIwMjRcXFwvMDlcXFwvMTYxMTI2MzBcXFwvQ29sbS1CdXJrZS1ieS1NaWd1ZWwtUnVpei0xOS0xLmpwZ1wiLFwid2lkdGhcIjpcIjMwOVwiLFwiaGVpZ2h0XCI6XCIyMTBcIixcImRlZmF1bHRcIjpcImh0dHBzOlxcXC9cXFwvd3d3LmhvdHByZXNzLmNvbVxcXC9pXFxcL25vLWltYWdlLnBuZz92PTlcIixcIm9wdGlvbnNcIjp7XCJvdXRwdXRcIjpcImF2aWZcIixcInF1YWxpdHlcIjpcIjU1XCJ9fSIsImhhc2giOiJhNzU0OTI1MjFlMGNjYmZhNjhmNzEwNTRiMDgwYzlmN2ExOGQwZjQ0In0=/colm-burke-by-miguel-ruiz-19-1.jpg)