- Sex & Drugs

- 29 Oct 19

The Whole Hog: Documenting the Seismic Moments of History for 1000 Issues

Over its 1,000 issues, Hot Press has documented and been part of many seismic moments in irish and world history.

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose, they say. The more things change the more they stay the same. How often have you heard it said? We’ve certainly used it, usually to grimly acknowledge that colossal social and economic forces continue to work as they always have. But how true is it?

Looking back over a thousand issues of Hot Press is less conclusive than we might have thought. True, many of the things that vex us most are still in evidence: inequality, health, housing, prejudice and ignorance. But great tides have washed others away: the crippling post-colonial sense of inferiority, poverty-induced emigration, the over-weaning and desperately unhealthy influence of the Catholic church, the suppression of dissenters, the oppression of sexuality and sexual identity. And we’re not Britain’s beef-rearing backyard any more.

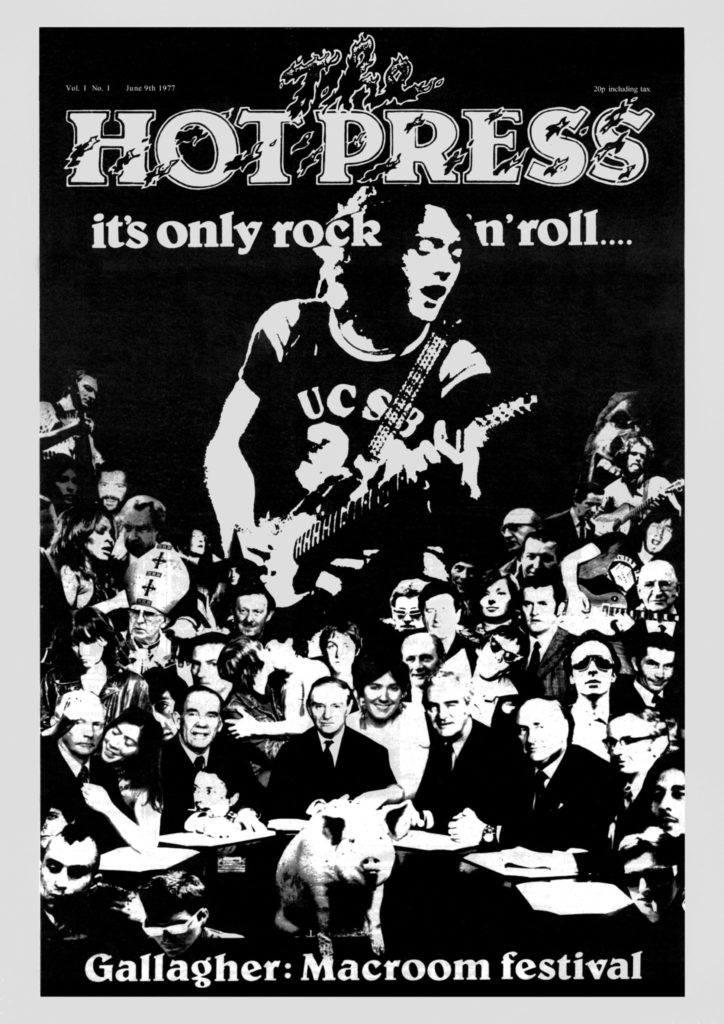

Look at our first front cover, with its collage of faces and images, with the late, great Rory Gallagher at the centre. It wasn’t just music. There were also politicians, clerics and personalities and, right there just behind then Taoiseach Liam Cosgrave, two men kissing. That wasn’t just mischief. It was a deliberate statement that there existed another Ireland out there, right under the noses of the patriarchy. Under their dead men’s hands it was at best ignored and at worst oppressed and repressed. We wanted it to be brought out of the shadows. We wanted to see it centre-stage.

Vol No

Vol NoThere was an election looming at the time. Liam Cosgrave’s coalition had been in power since 1973. Ireland had joined the European Economic Community: it is now called the EU. The Yom Kippur war happened early in the term of that deeply conservative Fine Gael-Labour government, followed by the OPEC oil embargo and, in turn, and unfortunately for the coalition, a global recession with cutbacks and restrictions and what we now would call austerity. There were no women in Cosgrave’s cabinet.

The 1977 election was a landslide for Jack Lynch and Fianna Fail, uber-boosted by their decision to abolish city rates and fund local government through general taxation, a mechanism that returned in all its glory during the water protests a whole generation later. It didn’t go well. They overspent. Everything seemed to inflate. Disaster was inevitable. And so it transpired.

Jack Lynch was ousted as leader of Fianna Fáil and Charles J. Haughey enthroned. He duly appeared on the telly one night to inform The Nation in his most serious and sonorous tones that “we have been living beyond our means.” We would have to tighten our belts. Austerity, in other words. As we now know, he should have been talking to himself but, of course, he wasn’t.

Ah yes, change and more change. Dramatic times there have been many, and yet much remains the same.

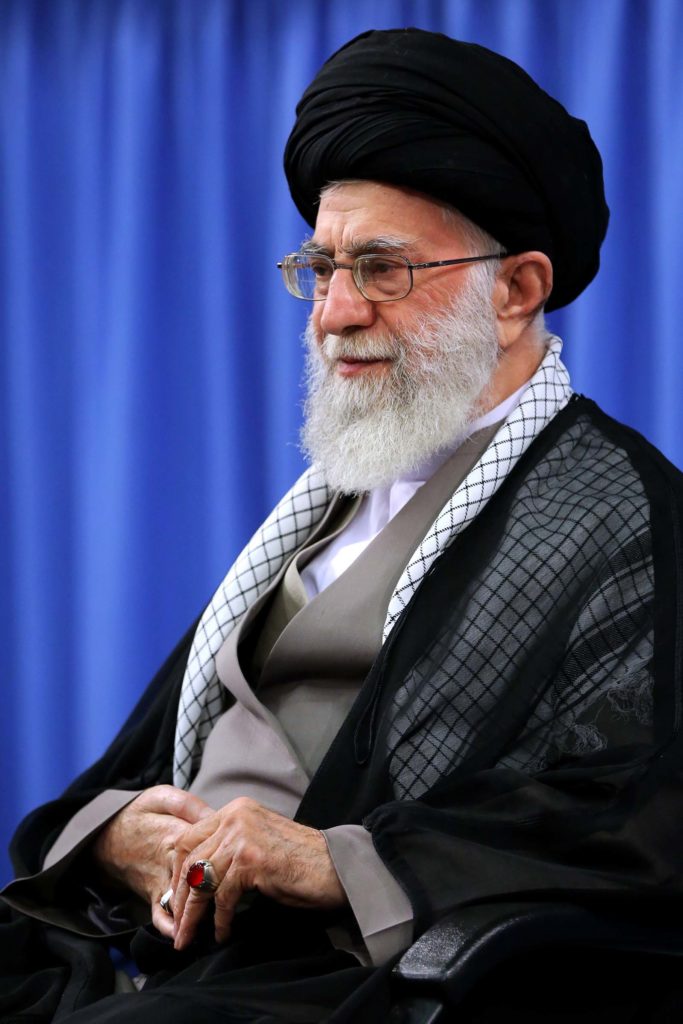

As we went to print in 1977, who’d have foreseen Ayatollah Khomeini’s 1979 revolution in Iran? Or the appalling man-made catastrophe of the Twin Towers attack in 2001? Should we have been surprised? The Palestinian Black September terror group had kidnapped Israeli Olympic athletes in Munich in 1972. And 1978 was just weeks old when IRA bombers left a large firebomb full of a kind of napalm outside the La Mon restaurant in Belfast, with 450 people inside. The fireball killed twelve and injured another thirty. It might have butchered far more. Terror was nothing new.

The Troubles were in full spate as we launched Hot Press and it’s fair to say they were a constant preoccupation. The inherent rightness of the civil rights movement had been subverted by loyalist mobs and the RUC – and then subsumed into a far less justifiable terror campaign home and away. The Jesuitical arrogance of the IRA in claiming to be the real government of the whole island was dissected in this column on more than one occasion with the message: Not in our name.

Vol No

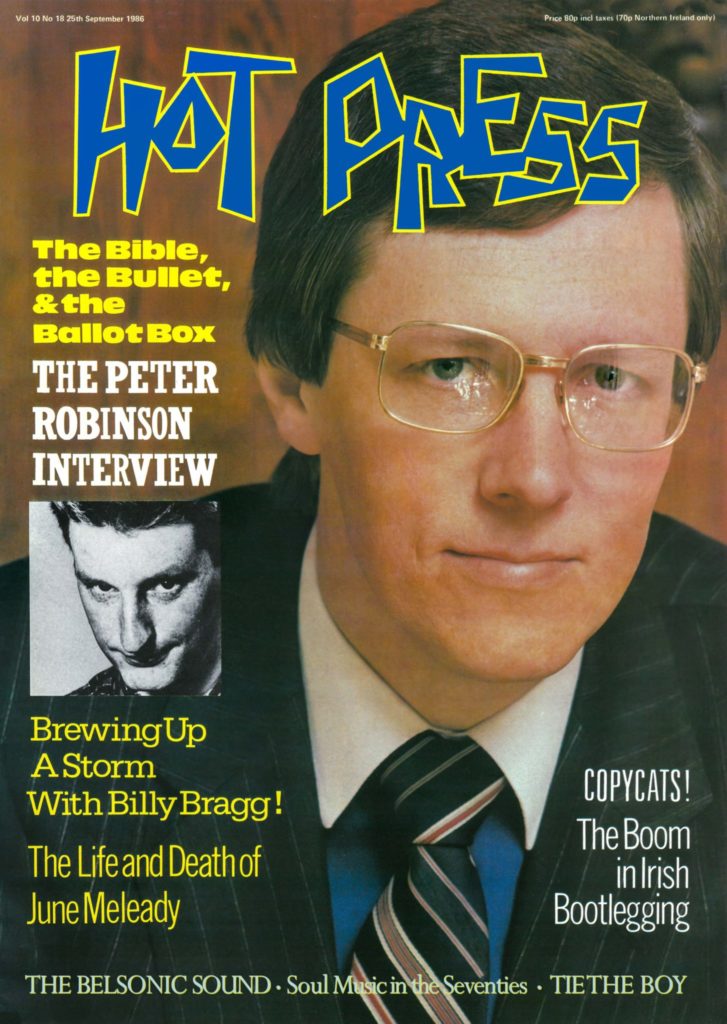

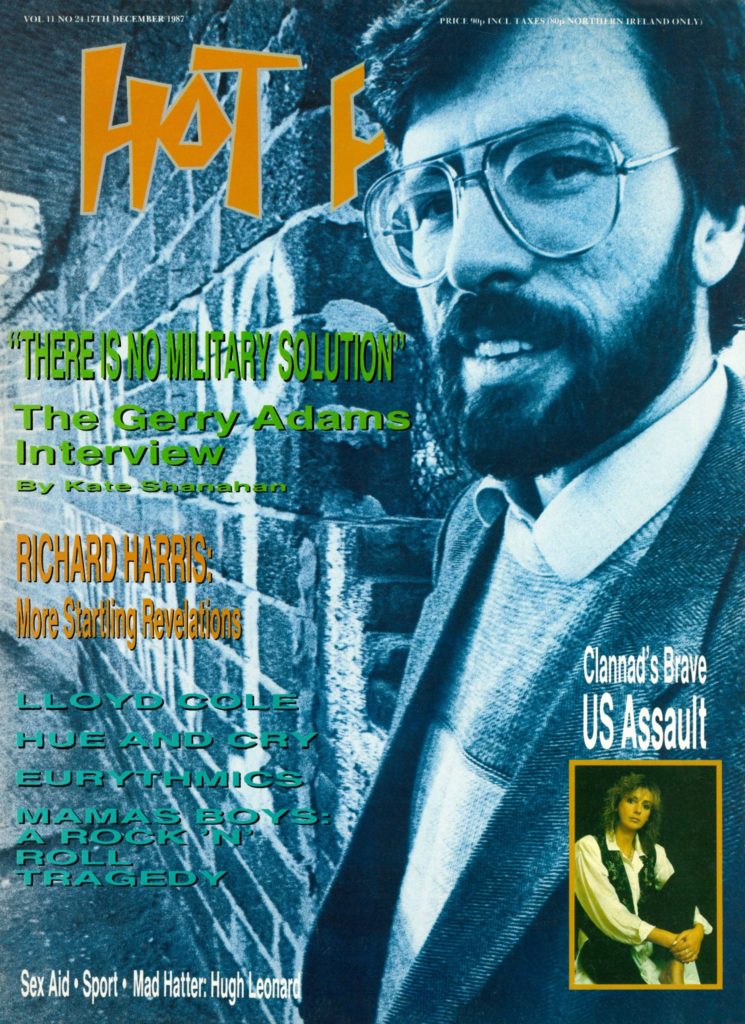

Vol NoBut it was vital to engage with what was happening in the North, and to hold the State – whether in Dublin or in London – to account for the wrongs which they perpetrated. Later, our commitment to a spirit of enquiry, discussion and debate on the future of the island of Ireland was reflected in the Hot Press interviews with a range of key figures, including paramilitaries on both sides of the conflict, as well as Republican and Loyalist political leaders, and establishment politicians, in which they revealed their thoughts and doubts and helped to generate the movement that led first to ceasefires and ultimately to peace. We had Peter Robinson of the DUP on the front cover in 1986 and Gerry Adams of Sinn Féin in the same coveted slot in 1987. It was the interview, conducted by Kate Shanahan, in which he said, for the first time in a really open, public way, “There is no military solution.” We made that the cover headline, and it resonated across the political spectrum. John Hume was listening. He picked up the telephone. The journey to the Belfast Agreement was a long one, but it started there.

Vol No

Vol NoWe are proud to have played a part in that process and warmly acknowledge the distance that the combatants travelled, in moving away from armed conflict. Everywhere on the island of Ireland, the mood changed. But in Down, Antrim, Armagh, Tyrone, Derry and Fermanagh the effect was much greater: hundreds if not thousands of lives that might have been lost were spared. But again, change, change, change is on the way. With Brexit upon us, here we are again, looking into the dustbin of history and contemplating the prospect of a new disaster. Let it not come…

Rosaries and ovaries: the fight for women’s reproductive rights

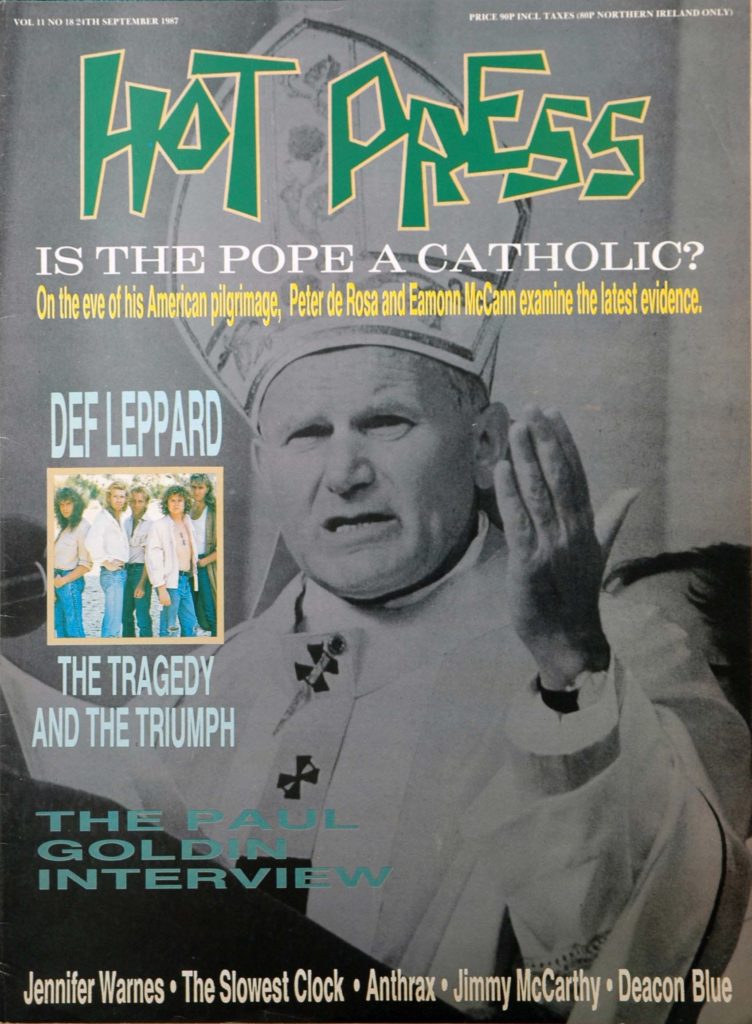

There was a mitred bishop on that first cover and with good reason. Ireland was a fully-fledged theocracy when we started out on the long road to now. The then Pope John Paul II came a-calling in 1979. It was intended as a triumphal visit that would copper-fasten the Church’s grip on Ireland for the foreseeable future. For a while it looked as if it had done just that. Inspired by his visit, those who wanted to exert control over women’s bodies and their fertility styled themselves as pro-life and set about inserting into the constitution what they imagined was an absolute prohibition on abortion. In September 1983, the 8th Amendment was approved by referendum after a bitter debate in which opponents highlighted the things that might go wrong.

At first, the papal visit and the Referendum looked like the building blocks of a new caliphate, a triumphant reiteration of Holy Ireland’s devotion to faith. A lot of young Irish people, especially graduates, upped and left, sickened by the acceptance, by the State, of the complete dominance exerted by Roman Catholicism. Little did we – or even more so the footsoldiers of Rome – know what loomed.

A mere three months after the 8th Amendment had passed a teenager by the name of Ann Lovett died while giving birth in a grotto in Granard at just 15 years of age. Her tragedy powerfully symbolised the cold, judgemental, and brutally isolating nature of the old Ireland that had created the 8th Amendment.

That old monolith unravelled thread by thread. Bishop Eamon Casey and Fr. Michael Cleary – who was later infamously exposed in all his arrogance and boorishness, in a Hot Press interview, again by Kate Shanahan – were the two cackling clergymen who cheer-led the Pope’s mass for young people in Galway. Both were revealed to be fathers. In exposing Eamon Casey, special mention must go to his sometime lover Annie Murphy, who withstood the far too apparent contempt of the host Gay Byrne, on her Late Late Show appearance, as she laid Casey’s hypocrisy bare. Byrne did many things very well and some of his radio broadcasts during which he listened to women’s stories were fantastic and progressive, but in this instance, he allowed his approach to be coloured by his own long acquaintance with the bould bishop. It was truly a #MeToo moment, way before such a thing existed.

Annie Murphy

Annie MurphyIt was as if the vaults had been opened. And now that they had, it was impossible to close them again. Revelations continued, over a period of many years, about the Magdalene Laundries and Mother and Child homes; about sexual abuse of children and vulnerable adults by priests like the monstrous Brendan Smyth; about the utterly scandalous cover-up engaged in by the hierarchy and the religious orders, who shifted known paedophiles from parish to parish and from city to city. And on and on it has seemed to go. That there were good priests and nuns whose calling allowed them to do positive and healing things in the world is not in doubt. They became more collateral damage as the sickness and the evil boiled to the surface.

The bid by the Catholic Church and its agents to control life in Ireland began well before the State was born, but it flourished in the years after independence, as women were driven out of public life, in a way that still inspires righteous anger. The Church’s calculated downgrading of women was driven by an obsession with sexual mores, and a fixation on controlling women in particular.

The cover-ups and quiet redeployments and “mental reservations” in which the top brass of the Catholic Church embarked, often with the collusion of the State and the Gardaí, were all intended to divert media inquisition and mask the loathsome exploitation of the weak for which they were responsible; the extent to which they had created a unique, Irish version of slavery; and to protect the Church from reputational damage – an objective which trumped all other considerations of justice or morality. Ironic that, given that it was the Church itself that launched the Spanish Inquisition.

Hot Press also battled throughout its 1,000 issues for LGBTQ+ rights. The headlines are there to be seen on the cover. When Will The Gay Bashing End? we asked. A Woman In A Man’s Body: The Story of an Irish Trans-sexual. That was in the early 1980s. The Queering of Ireland. Dublin ’94: Young Gays Go For It. Graham Norton On The Homophobia Brigade. Right up to our two covers before the Marriage Equality Referendum that showed, respectively, two women kissing and two men, with the headline: Vote Yes.

The background to the changes that took place should be acknowledged. Many of those who had battled on the pro-Choice side in the 1983 referendum and who supported David Norris’ campaign for the legalisation of homosexuality refused to give up the fight. Gradually, the sands shifted. Hence the joy that greeted the result of the Marriage Equality referendum and subsequently the Repeal of the 8th Amendment. Free at last!!

Dublin Pride, Saturday 29th of June 2019. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

Dublin Pride, Saturday 29th of June 2019. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.And yet, they haven’t entirely gone away, the gang that Hot Press famously dubbed The Anti-Happiness League. A well-organised and well-funded guerrilla-style campaign is underway as anti-choice activists, still maliciously claiming the ‘pro-life’ tag, take a leaf out of the American far right playbook, by mounting pickets and harassing clients of clinics where abortion services are provided.

But the old, deeply insidious power is gone. Church attendances have fallen dramatically and only a handful of priests are ordained each year. More importantly, the surrounding society has changed.

The fall from grace of the old order was thanks, in great measure, to the media in Ireland. Journalists were able to sustain their own investigations, even in the face of much official hostility. The media aren’t short of critics, often deservedly so, but in this arena what was achieved was often brilliant. They say that the truth will out. Not always. But in relation to the rank abuses perpetrated by the Church and its clergy, and the horribly damaging effects of the marriage of convenience between Church and State, it did. And we are much the better for it.

Something rotten this way comes

The Roman Catholic Church in Ireland was just one of the rotten apples that festered in the barrel of Irish life. There were many others. In February 2000 this columnist wrote:

“Nobody could have forecast that we’d be cleaning out the stables in 1999. That we’d have exposed the corruption and/or wheeling-dealing of cattle barons, politicians, priests, business people, financial institutions, certain (local Government) public servants and the rich, in no particular order. And that judges would resign.”

Throw in the Garda Síochána and you have the full set. Who can forget the findings of the Morris Tribunal on the monumentally corrupt activities of leading figures in the Donegal division of the Gardaí? Or the extraordinary saga whereby, more recently, Sgt. Maurice McCabe was first done down but later vindicated with honour. You could hardly make it up.

Tribunal followed tribunal, covering a very broad range of scandals. At one point it seemed that they’d never end. Esteemed jurists did very well out of them, but that was sourly accepted by everyone as a price worth paying for what we discovered. Many things triggered the cascade of information and investigation including aggrieved developers, horrified families and fuming whistleblowers. And, again, we must salute the newshounds who stuck to the trail when all seemed lost.

So are we all squeaky clean in 2019? No, not quite. But we’re getting there. Indeed many foreign companies now regard Ireland as one of the least corrupt places in the world, in which to do business. That’s not to get all dewy-eyed. Rather, it’s to acknowledge progress. But the price of freedom is eternal vigilance. And robust, independent systems.

Boom and bust: sure it’s a way of life!

A thousand issues ago, Ireland was slip-sliding away down the greasy chute. The oil crisis flicked a switch. The 80s weren’t good here, trust me on that. Prices and interest rates inflated, wages didn’t. Unemployment was rampant. Likewise bad fashion. There were housing shortages yet also empty houses. We were bust. But gradually we clawed our way back.

Maybe that’s what made the Celtic Tiger boom, when it came, in the first decade after the Millennium, so giddy. We weren’t used to the oxygen. Or the drugs. Or, especially, the money which, of course, had become so much cheaper after we joined the euro. It was madness. But not that many people saw what was coming.

The banks were the main problem, flinging money around like drunken sailors. All fiscal rules were bent or broken. There’s a boxing adage: “Never stick your chin out and ask to be hit.” But they did. Personal debt and bank debt expanded far beyond what was sane or prudent. The global financial crisis kicked off in 2007. When the crunch came here, in September 2008, the banks were fucked and so, in due course, were we, bailing them out to the tune of gazillions, money that we’ll still be paying off for another generation. Back to bust, only this time with knobs on.

We are still feeling the effects and will do for many years to come.

No resources? No problem. We’ll be our own resource.

One of our abiding beliefs, when we launched Hot Press, was that Ireland could produce a publication that would be the equal of anything similar produced in the US, the UK or indeed anywhere in the world. Our attitude was: you don’t need to go to London. And anyway, we shouldn’t have to. The same applied to musicians. We needed the infrastructure here in Ireland that would enable Irish musicians and bands to base themselves on home turf. To foster and encourage that ambition was a central part of our mission.

This was a political stance. It was also cultural: if we take the notion of independence seriously then we have to start acting that way. For sure, it was economically difficult. We were trying to match Rolling Stone, in a market about a sixtieth of the size. Or NME, in a market less than a tenth of the size. We’d have to work like fuck, we knew. And so we did.

That notion, that Ireland should be doing its own thing, was echoed in many spheres. Take education. During the 1960s policymakers had decided that investment in education was to be a cornerstone of Irish economic and social development into the future, an inter-generational social contract, if you like. It took time – but in the long run it paid off. We didn’t have coal or oil but we had people. As the 20th century closed and the 21st dawned, our educated workforce proved a singularly valuable resource.

Nowhere is this more evident than in music. Horslips had set a trend by not taking the boat. Punk, while attracting many to London, also fashioned a do-it-yourself ethic. U2 decided to base themselves in Dublin, before going on to become the biggest band in the world.

Subsequent musical generations followed, each standing on the shoulders of earlier giants, each building the legend. Film and theatre were drawn in too. Think of of Alan Parker’s triumphant take on The Commitments (1991); of Neil Jordan’s Oscar-winning The Crying Game (1992); of Jim Sheridan’s In The Name of the Father (1993); of John Carney’s Once (2007) – with Glen Hansard and Marketa Irglova winning the Oscar for ‘Falling Slowly’ – and Sing Street (2016); of Lenny Abrahamson’s Room (2016). Riverdance, which was transformed from a 12-minute piece for the interval at the 1994 Eurovision, composed by Bill Whelan, produced by Moya Doherty and directed by John McColgan, revolutionised Irish dancing and played no small part in marketing Ireland to the world.

The Crying Game

The Crying GameNobody questions this in 2019. This is thanks to many things, technological change being one: you can do so many things at great speed and across huge distances now. Musicians can record music together while on different continents. Information travels at the speed of light. But it wasn’t like that then.

The Hot Press Interviews

We always did interviews, of course, with musicians and writers and activists of various stripes, so why not politicians? And the style of interview was important. We tended, as was the case elsewhere, for example the NME in Britain and Rolling Stone in New York, to mainly let the interviewees speak for themselves, to let the quotes stand with relatively little change or interpretation. So when Charles Haughey agreed to an interview, the style was set. If he said ‘fuck’ we’d print it! It was a sensation. At the time it actually did him little harm – but the template had been created. Our interviewers included John Waters, Joe Jackson, Michael O’Higgins, Kate Shanahan, Liam Fay, Liam Mackey, Olaf Tyaransen, Jason O’Toole, Stuart Clark, Roisin Dwyer – and more. Hats off to them all.

33AIDAN WALSH MASTER OF THE UNIVERSE

33AIDAN WALSH MASTER OF THE UNIVERSEFRIDAY 17 AUGUST

AIDAN WALSH AND CHARLES J HAUGHEY

PAULINE CRONIN 087-2629967

Living in a digital world

At this stage it’s hard to remember the old days, when mobile phones were the size of a peat briquette and sported aerials a metre and a half long and were largely the preserve of builders who bellowed into them believing, like Dom Joly’s memorable alter ego in Trigger Happy TV on Channel 4 (2000 to 2003), that shouting enhanced the technology. Maybe it did.

The World Wide Web (WWW), which is the principal mode of communication for most of the world now, dates from 1992 (Hot Press was a teenager by then!) – but it wasn’t till after the turn of the Millennium that people really started to see its enormous potential. And mobile phones, the most ubiquitous of all communications media now, only became smartphones with Apple’s iPhone in 2007.

As for social media, the real expansion began with LinkedIn and Skype (2003), Facebook (2004), YouTube (2005) Twitter (2006) and WhatsApp in 2009. You had to wait until 2010 for Instagram; 2011 for Snapchat; 2012 for Tinder; 2013 for Google Hangouts and – well, it’s a wild ferment, as they say in natural winemaking and artisan beers.

The point is that it’s all very recent. During our thousand issues, Ireland – like the rest of the world – had to make that leap from pre- to post-digital. People’s hands are changing shape from scrolling and texting. It’s okay to walk along a street speaking out loud to nobody now, even shouting. We just assume you’re on a call. Public transport carriages are almost as quiet as libraries – unless, of course, some drink-sodden would-be hooligans are creating a rumpus that they can record and bang up on their social media feeds.

All fine and dandy, as far as it goes. But there is a dark side to all of this, or perhaps several.

They did it by stealth, and to an extent at least Governments colluded – beginning with the decision to give them “Safe Harbour” status in the US – but social media companies have created a new kind of business: surveillance capitalism. It has emerged bit by bit that social media corporations have been harvesting data – often without adequate permissions and frequently covertly – from every single person that uses any of the major platforms or who “googles” for information.

They use the information that has been surreptitiously collected – and sell it to third parties – in a way that herds users into self-multiplying echo chambers. The effect has been like a poison injected into the veins of the body politic. The way social media companies work is bad for democracy. And indeed, as has been emerging in The Guardian’s recent probe into climate denial, the big tech companies have colluded with many of the corporations that are primarily responsible for the environmental disaster that looms ever larger across the world. Social media companies and tech platforms – including YouTube – are also the principal vectors in the rise of racism, the far right and communal stupidity. Twitter is the chosen medium of Donald Trump.

It would be wrong to suggest that it is all bad. Social media was important in the historic election in 2008 and 2012, of Barack Obama. Here in Ireland, an effective use of social media made a difference in the campaigns for equal marriage rights and repealing the 8th; and the progressive actions of the Swiss movement Operation Libero and, of course, the gathering campaign to tackle carbon emissions.

On a more personal level, for families and friends all over the world, Skype, Facetime, WhatsApp and Hangouts, have been a remarkable boon. When mobiles were as big as briquettes nobody could have anticipated that two farmers could communicate in real time, and with video, from fields on different continents. But they can. Or that families could stay in intimate and constant contact, and sight, a great benefit for people like the Irish, who are highly mobile, technologically fluent and very family-oriented.

Ireland has done well out of all this, providing a home for the companies as it previously did for high-tech manufacturing and the pharmaceutical industry. Tax issues have arisen: they need to be addressed. So also must the wider, political issue of responsibility. Hot Press has always believed that Facebook, Twitter and the rest are publishers. The level of cynicism and chicanery which has been enabled by them is dangerous. So too is the largely unfettered extent of hate speech, deliberate libel and divisive propaganda. That much of this occurs in ads, and social media companies make fortunes out of it, cannot be right. Those profiting from it all must be forced to accept that they cannot evade reasponsibility any longer.

It is an issue for Europe. But Ireland must play its part.

Because we’re worth it

Early in the social media breakthrough years you’d open-up to find a box or a scrolling header or footer that said ‘trending now’ and it would point you to a link. Nowadays it’s called ‘going viral’. It isn’t always positive. Not by a long shot.

Digital communications are so fast and capacity so great that anything – even the most appalling lies – can disseminate in minutes. Then there’s the creation of that new occupational category, influencer – signifying bloggers and vloggers who have amassed a significant following and accordingly, in some cases, great wealth by plugging products. Who, in 1977, would have envisaged the Kardashians? But there they are. And they are not alone.

One key trend that emerged over the course of the thousand issues is the veneration of an even emptier kind of ‘celebrity’ – that is people who are known just for being known, rather than any achievement, accomplishment or ability. The emergence of Reality TV – from Big Brother onwards – was a key driver of this phenomenon. Love Island, a huge hit during the summer of 2019, is its lineal descendant. As a result, we’ve seen hundreds – or maybe thousands – of people who were famous for fifteen minutes. Few have sustained.

A side-effect has been a significant rise in narcissism. It’s all about the selfie and presenting an ideal. Look how good my life is! Photoshop works wonders. See how fabulous I look! And it has, for some at least, become a nightmare: to not be what is widely accepted as ideal. Filters can only do so much. Against that background, there has been a huge rise in what has been called body dysmorphic disorder – a mental health problem in which you can’t stop thinking about perceived defects or flaws in your appearance.

The question is: can we find a balance that makes sense for the majority? Gyms have opened everywhere and that’s a good thing. There’s a growing interest in fitness and health. And yet Ireland has one of the most expensive medical systems in the world. There is something that doesn’t add up. The problem, as successive Ministers for Health since 1977 have discovered, is identifying why.

The Age of Rage or maybe it’s just time for coffee?

Lifestyle historians might struggle to find a defining characteristic for the last forty years. It’s the Age of Rage for some. Shame and shaming have to be there somewhere closely associated with greed and cowardice. Think of the bankers. Think of shameful and shameless Donald Trump. Wellness has to be in there too. On which, it’s a case of information overload regarding what and how to eat, what to drink, how to exercise, which foods are good or bad for hundreds of afflictions both real and imagined, what’s the new superfood or supplement, little of any of it based on real science. It’s an upswelling of interest and commerce that takes in a whole slew of health-ish stuff with a general focus on you. Because you’re worth it, of course.

Trump Baby Blimp flies in Dublin during a protest against Donald Trump's visit. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.

Trump Baby Blimp flies in Dublin during a protest against Donald Trump's visit. Copyright Miguel Ruiz.A thousand issues ago you buttoned up about your stress and distress but more recently we’ve all begun to tune in to mental wellbeing. It’ll take time and money. Mind you, there’s no hell quite like sitting beside someone on a bus as they unburden themselves about who’s been leaking their private Instagram feed. Some things should stay buttoned!

Techniques for meditation and relaxation have been around for ages, but they’ve generally been on the fringes of polite society. Omming and awing, eh? But not now. Mindfulness has gone mainstream. In its pure form it’s very good, like a kind of secular Buddhism. But doesn’t it rather lose itself when implemented as a company strategy by large corporations? And then there’s authenticity. Out of the Great Recession and the ascent of millennials to the mainstage came big beards and small companies, coffee roasteries and artisanal beers, local gins and small plates and foraged foods and sustainability and bags made of linen or potato starch. Bean to cup, nose to tail. Reminds us how good Bewley’s was back in the day. And it’s all good.

The End is Nigh: sustainability and the environment

We’ve been saying this for a long time, but here’s the brutal reality: if things don’t change we’re fucked. To say that we have been banging this drum louder than most for a long, long time is to put it mildly. Here is what The Whole Hog had to say, early in 2001:

More or less everybody knows we can’t sustain things the way they are going. We can’t build houses fast enough. And besides, who wants to live in south Kildare and work in Dublin? The whole conceit is out of hand. Really.

It isn’t just that we haven’t the houses or big enough roads. It’s more. Look beyond the smugness of the Beamer dot.com rich-as-Croesus brigade and you can see we’re practically at the top of the rapids and we’re going over. At parish level there’s the Galway refuse problem. But at the global level there’s everything else. The Beamer and the top o’ the range Merc use a lot of fuel. And there’s the rub.

You know the rest. The inter-governmental panel on climate change is predicting killer heatwaves in the near future. In their view, having examined everything, from tree bores to ice cores, is that the earth is warming faster than at any time in the last 10,000 years and man is causing the increase by burning fossil fuels, cutting down trees and making changes in agriculture. But we keep to our growth targets. We may like the sound of some of it – milder winters up north – but in truth it will be bad news across the spectrum. Further south there will be intense heatwaves that will kill many. Insect pests will proliferate. There will be an increase in malaria. The Mediterranean will be too hot for holidays in July and August. Like the sound of that?

There will be no more skiing. Glaciers will melt. This will be a big problem for communities dependent on them for water, as they do in the Pyrenees, the Alps, the Andes and the massive Himalayas/Karakoram range. Many crops won’t grow. Many forests will die, because it will be too hot and there won’t be enough water. ***

From 25-03 (28 February 2001)

Extinction Rebellion rally at O Connells bridge, Dublin. Friday 19th of April 2019. Copyright Miguel Ruiz

Extinction Rebellion rally at O Connells bridge, Dublin. Friday 19th of April 2019. Copyright Miguel RuizIn a way, it is hard to believe. You could write exactly the same thing today, and it’d be equally true. Except that the wriggle room has contracted so enormously that the sirens have started to go off. Maybe the growing consensus is approaching critical mass. The recent European and local elections in Ireland showed a strong resurgence in green thinking. Schoolchildren and students worldwide are mobilising and going beyond passive resistance and fingerwagging to direct action. Make no mistake, taking corrective action is going to hurt. It will change many things we now take for granted. But we’ve got even less choice now than we had in 2001. There’s no time left for stalling. It’s action stations – or curtains.

The drugs trade

Was it that the war in Afghanistan freed up a vast harvest of poppies? Or the CIA connived in its release? Might corruption and US-backed military politics in South American countries have provided cover for the growth in coca plantations and their downstream product cocaine – a drug of choice in the music, finance, sex, fashion and media industries? And what about clever dicks circumventing regulations to make new synthetic drugs and vast amounts of money? Where does the announcement of the so-called War On Drugs, first by President Richard ‘Tricky Dicky’ Nixon in 1969 and then by President Ronald Reagan in 1982 – fit into the crazy tapestry that has taken shape around the issue of narcotics over the years since 1977?

It can be filed under failure, that’s for sure. The Drug Policy Alliance estimates that the United States spends $51 billion annually on what are termed anti-drugs initiatives. A total of 2.3 million people – almost 1% of the entire population of the US – were imprisoned during 2016. A lot of them were for drug-related offences.

Drug fashions change. They both reflect and affect the times.

In Ireland we’ve had hash, heroin, cocaine, ecstasy, handmade drugs, opioids, each triggering new issues and questions. The growth and diversification of supply has led to major growth in gangland activities. The profits are huge but you may well die young. The social damage caused by drug abuse has become almost secondary to the warfare over the proceeds. This isn’t on the same scale here as in Mexico where, according to the US Council on Foreign Relations’ Global Conflict Tracker, 150,000 people are estimated to have died since 2006 due to organised criminal violence. We’re far smaller, but it’s still a wretched waste of time, money and lives.

Clearly, the ‘war’ is not working here either. The illegal trade continually infiltrates and corrupts. Like a river or a virus, when one avenue is closed off it simply finds another. If the demand is there, the supply will follow. Over 70% of inmates in Irish prisons have addiction issues. In a way, that says it all.

Hot Press has long advocated legalisation – or decriminalisation at least – as the best way forward. Finally, it seems that the world is catching up. Here, we’re still stuck with the old prohibition paradigm, the idea that making it illegal will close off supply and thereby solve the problem of demand. It hasn’t worked and it won’t. Elsewhere, the trend towards legalisation, as opposed to decriminalisation, has been gathering momentum. A slew of US States have legalised the sale of cannabis. Guess what? The sky hasn’t fallen. And they’ve harvested billions of dollars in tax. There is no perfect solution for the very simple reason that people are not perfect. But to take drugs out of the hands of criminals would be one of the biggest and most positive developments we could wish for. We might even get there before the 2,000th Issue of Hot Press. Olé olé olé olé! Getting to like ourselve...

It’s hard to pinpoint exactly when it happened. Perhaps it was when the Green Army descended on Germany in 1988 and everyone had a great time. Then there was that heady moment when Dublin and Galway were coming down with stars of music and literature, thanks to the artist’s tax exemption scheme – one of the good things Charles Haughey did in his time - outdoing each other in singing our praises. Or was it when U2 pilgrims started to appear in Ireland? Or the headline in the Irish Times over Peter Byrne’s report on Ireland’s victory over Italy in Giant’s Stadium in New York that seemed to say it all: Triers No More.

It would be wrong too to ignore the Eurovision triple whammy and the extraordinary impact of the very first Riverdance. Later you had Munster’s Heineken Cup odyssey. Fail, fail again, fail better. Until they won. And then Leinster. And what about the Dubs and their five in a row? Somewhere in it all most of us (though certainly not all) lost the ould inferiority complex. We got used to the idea that we could win, could do success. Yeah, Irish people have long done it – but this was different: it was a collective realisation. And everyone seemed to love us. True, our period as the coolest people on the planet couldn’t last and didn’t. Yet, right around the world people want to have a bit of Irish in them (though not necessarily in the way Philip Lynott meant!) It’s what they now call soft power!

To close:

And so, you might say, it’s déjà vu all over again. The wheel has turned full circle. An election looms here as the UK turns its back on Europe and indeed Ireland. So long and thanks for the memories. It doesn’t always seem so, but we’ve emerged from the dark. New generations stand proud on the shoulders of warriors who went before. Let nobody think it was easy because it wasn’t. Let nobody think it will remain the same without hard work and constant vigilance because it won’t.

There are still so many clouds: Brexit, addressing the green agenda, bringing order to the chaos of the health system and providing sufficient quality housing to meet the needs of an expanding population. So, yeah, we’ve all come a long way but, as Joe Ely says, the road goes on forever.

The Hog

RELATED

- Sex & Drugs

- 18 Apr 23

Trans and Intersex Pride Dublin reveals plans for 2023 Pride march

- Sex & Drugs

- 06 Apr 23

Bealtaine 2023 festival features a range of queer events

- Sex & Drugs

- 11 Dec 25

What's really going on with the global drug trade?

RELATED

- Sex & Drugs

- 24 Oct 25

New Dealing With Drugs podcast episode out now

- Sex & Drugs

- 05 Sep 25

Hot Press launches new Dealing With Drugs podcast - Episode 1 out now

- Sex & Drugs

- 21 Mar 25

Documentary about Ireland's first supervised injection facility to air this March

- Sex & Drugs

- 13 Feb 25